Space chameleons or space cowboys - neutrinos and their mysteries

After three consecutive weeks in which I discussed dark matter, it is time to vary subjects a little and move on with something different. Please don’t worry if you are a big fan of dark stuff, I will come back to dark matter sooner or later.

A couple of years ago, I started to get interested in the phenomenology associated with neutrinos. These interests gave rise to two scientific publications in 2021, another one being in the pipeline for 2022. However, I won’t discuss those publications today. Although they are definitely worth a full post (at least from my own perspective, which is disputable of course), they require some prerequisites on which I have not written yet. The present blog is thus dedicated to filling this gap, including basic facts about neutrinos.

I explain below how current knowledge about neutrinos has been built over the years, and why we can consider that neutrinos belong to the darkest parts of the Standard Model. As it is now a kind of tradition for my blogs, anyone pushed for time could get the bulk of the information shared today in the last few paragraphs of the blog. As usual, feel free to ask anything in the comments section, to which I will try to answer in the best possible manner.

For those interested in starting with a question, there is a strong link between the futuristic image below (that is not futuristic at all by the way) and neutrinos. Can you guess what it is?

[Credits: Original image from IceCube (NSF)]

A particule that cannot be detected…

The neutrino story starts in the first half of the 20th century, when physicists of that time were trying to understand how beta decays were working. Beta decays are processes in which a given atomic nucleus decays into another atomic nucleus together with the emission of an electron.

In order to understand the dynamics of such processes, there are two golden rules of physics that need to be stated. The first one is that energy is conserved in any process. This rule was already discussed quite a bit in the previous blog, as it is the one on which we rely to reconstruct a potential signal of dark matter at particle colliders like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

In addition, there is another important conservation rule that needs to be introduced: electric charge conservation. This means that in a reaction the sum of the electric charges of the interacting bodies must be equal to the sum of the electric charges of the produced bodies.

Recalling that an atomic nucleus comprises protons (of a positive electric charge of +1 unit) and neutrons (of a zero electric charge), any atomic nucleus has a positive electric charge equal to its number of constituting protons. We are now ready to go back to the process of interest in which one atomic nucleus transforms into another plus an electron. In order to balance the created negative electric charge of the electron, the initial-state atomic nucleus must have one fewer proton than the final-state nucleus.

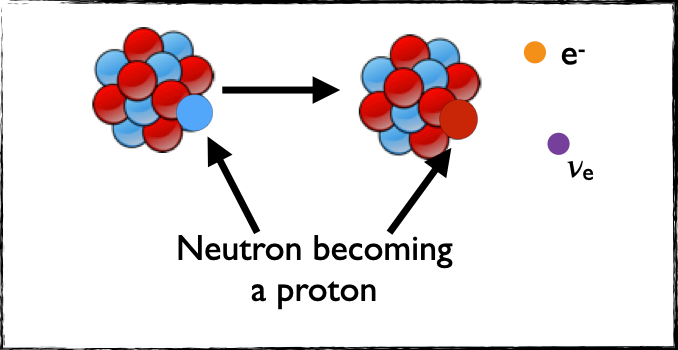

In other words, a beta decay is a process in which one atomic nucleus comprising some neutrons and protons decays into another nucleus comprising of one more proton and one fewer neutron, and an electron. As one beautiful image is better than many words and as I have zero artistic skills (special thanks to @robotics101 for reminding this to me), I am afraid that the only image illustrating this will be the one provided below (my poor readers…).

[Credits: @lemouth (and his ‘super’ artistic powers)]

Here, we can see that there is an atomic nucleus on the left that decays into another atomic nucleus (shown in the right part of the figure). Both nuclei are made of protons (red circles) and neutrons (blue circles), and one neutron is converted into one proton in the decay process. This comes together with the emission of an electron (the orange circle). Let’s ignore for now the purple particle (i.e. the neutrino), as in the first half of the20th century such a particle did not exist.

In such a process the electric charge is conserved: one neutron of charge zero is transformed into one proton of charge +1 and one electron of charge -1. However, the energy has to be conserved too. Doing the math (and using Einstein’s theory of special relativity), it turns out that the energy of the electron is fully determined to be equal to a given value.

Experimentally, this was however not the case. It was observed that the energy of the electron could take any value between zero and the expected value. To find an explanation to this problem, ‘Pauli did a terrible thing’ (using his own words, as shown here): he postulated that an invisible particle that could not be detected was emitted together with the electron. Energy conservation was restored as this particle was then sharing the available energy with the electron.

Fermi theorised the concept shortly after Pauli’s proposal, and Reines and Cowan demonstrated the whole thing experimentally in 1956. They relied on 400 litres of water containing cadmium chloride, and a bunch of electronic devices observing the water tank. From there, they waited for a neutrino to collide with a proton in the water to produce a positron and a neutron (a kind of inverse process as the beta decay process).

After having observed a few events, Reines and Cowan upgraded the neutrino from its status of being an imaginative object to a status of being an existing particle.

From one to three neutrinos

Fast forward from the 1950s to today, we know that there are three species of neutrinos: the electron neutrino (the one involved in beta decay processes), as well as the muon neutrino and the tau neutrino. They are moreover all very weakly interacting, so that thousands of billions of neutrinos flow through any human body every second, without leaving in there any track.

The existence of the muon neutrino was hypothetised soon after the discovery of the muon (the big fat brother of the electron) from the study of cosmic rays, as detailed in this earlier blog. In trying to understand how the weak force worked, physicists were conducted to postulate the existence of a second neutrino. The reason is that particles should be organised in pairs from the perspective of the weak force (up and down quarks, strange and charm quarks, electrons and electron neutrinos, etc.).

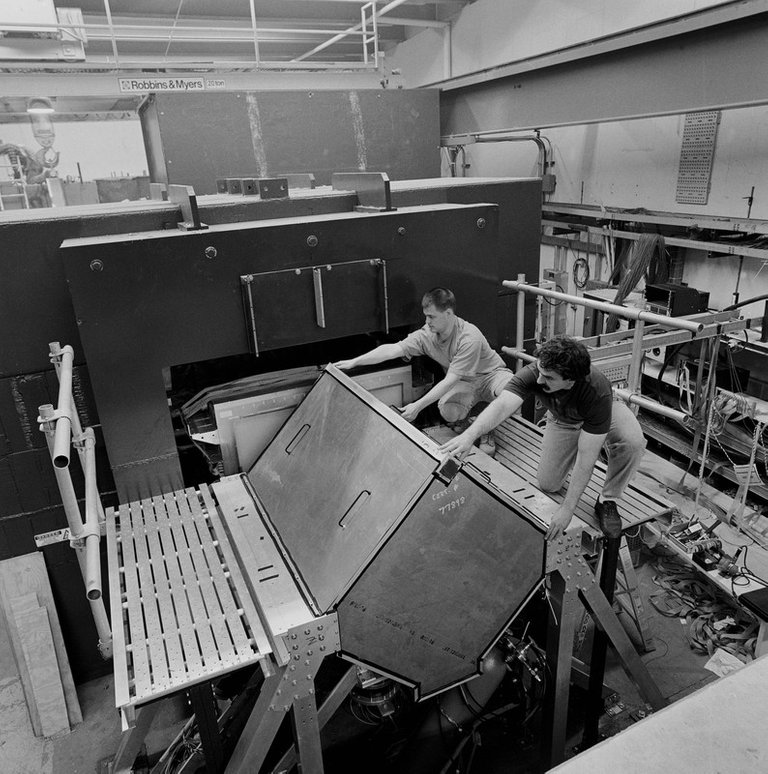

The experimental confirmation of the existence of the muon neutrino involved the production of the first beam of neutrinos ever. This beam was prepared by firing accelerated protons onto a fixed target. The particles produced in that reaction were then flying further away, over tens of metres, before decaying. The associated decay products were finally stopped by a 13.5-metre-thick wall of steel.

Were all produced particles stopped by the wall? Of course not! All neutrinos produced in the reaction survived, by virtue of their very-weakly-interacting nature. The whole apparatus hence resulted in a pure beam of neutrinos starting right after our wall of steel.

Physicists could in this way build a detector on the other side of the wall to study phenomena originating from the interactions of the neutrino beam. They adopted the choice of constructing a 10-ton spark chamber. Why such a huge detector? Well, neutrinos being interacting very rarely, large detectors are in order to maximise the chance to see some events.

A few events were eventually observed in this detector, and those events were compatible with the fact that the Standard Model (of that time) should include two species of neutrinos: the electron neutrino and the muon neutrino.

[Credits: CERN (CC-BY-4.0)]

In their hunt for new particles, physicists discovered the tau lepton in the 1970s. They observed 64 events resulting from a collision process in which one electron and one positron collided and generated one electron, one muon and some missing energy (once again, this comes from energy conservation).

In order to understand how such events could arise, it was required to postulate the existence of a new lepton, the tau lepton. In the process considered, tau leptons were pair produced in electron-positron collisions. Tau leptons being unstable, one of the two produced taus decayed into an electron (together with missing energy carried away by neutrinos), and the other one in a muon (also together with missing energy carried away by neutrinos). Among all produced neutrinos (there are four of them), two were tau neutrinos.

Tau neutrinos were however much tougher to find and detect directly. In the above process, we only observe missing energy, and it is impossible to tell which fraction of the missing energy is attached to which invisible particle. Only the sum of all invisible contributions is detected.

We hence had to wait… until July 2000 to discover the tau neutrino (see here). I was born for already many years, and I even started to be seriously interested in particle physics at that time (for those interested in my life, I was studying something a bit different in the early 2000s).

The DONUT collaboration investigated the interaction of an intense beam of neutrinos with a detector, and expected to observe the collision of some tau neutrinos from the beam with the iron atoms making a 15-metre-long detector.

After three years of hard work, they observed 12 events in which one out of the trillion of tau neutrinos of the beam reacted with an iron nucleus. This observation was made possible as the detector comprised an alternance of iron plates and photographic emulsions. The studied process led the generation of a tau lepton that resulted in a 1-millimetre-long observable track. Understanding what happened in the emulsions is what took three years.

[Credits: Fermilab]

Neutrinos as chameleons!

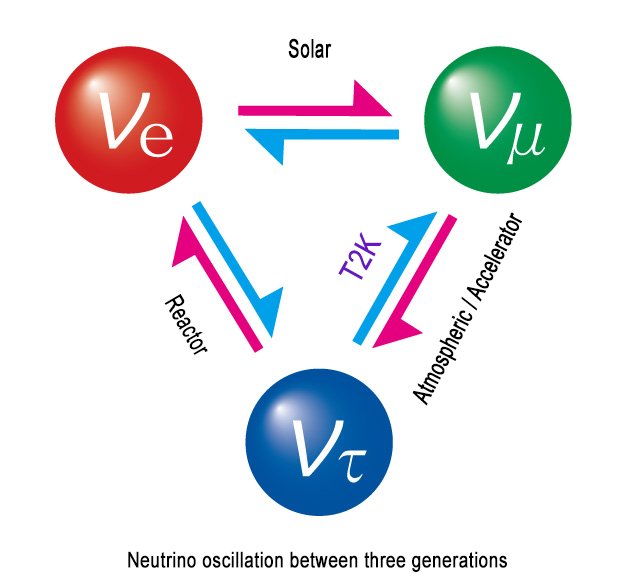

Let’s summarise where we stand so far. The Standard Model contains three species of neutrinos (the electron neutrino 𝞶e, the muon neutrino 𝞶𝝁 and the tau neutrino 𝞶𝜏). All these three neutrinos have been experimentally confirmed, as discussed in the previous paragraphs. In order to incorporate neutrinos with right properties in the Standard Model (i.e. relative to observations), all neutrinos have to be massless.

While this is not a problem stricto sensu, there were important issues with neutrino phenomena, some of them dating back from the 1960s. For instance, the amount of electron neutrinos created in all nuclear reactions happening inside our Sun appeared to be incorrect. When burning its fuel, the Sun indeed emits a large amount of neutrinos that we can observe on Earth. However, it turns out that two thirds of these solar neutrinos were reported missing.

One of the suggestions to solve this puzzle was that neutrinos of a given species could change nature within their propagation. A significant fraction of the electron neutrinos produced inside the Sun would hence be converted to muon and tau neutrinos during their 150-million-kilometre journey to Earth.

[Credits: J-Parc]

In addition, the relative amount of muon and electron neutrinos produced in the atmosphere through cosmic ray interactions was measured to a value non-consistent with the Standard Model. As another example, we can also mention issues with neutrino fluxes emerging from accelerators. And so on… However, all those problems could be solved at once by assuming that neutrinos could change nature during the course of their propagation.

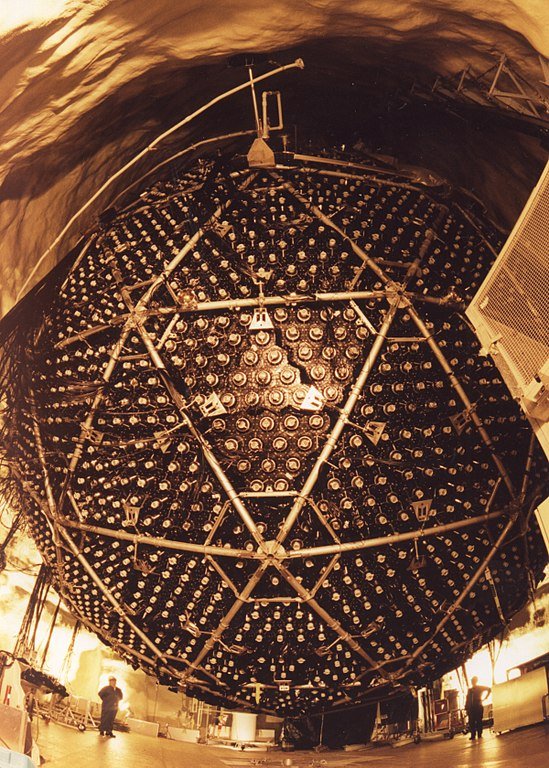

The puzzle was finally solved thanks to the hard work around two key experiments, at Super-Kamiokande (Super-K) and at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO). This work led to the Nobel prize in physics in 2015 (see here).

Super-K was a tank of 50,000 tons of extremely pure water surrounded by 11,000 light detectors. I remind that neutrinos are very weakly interacting, so that huge detectors are in order to maximise the chances to detect rare associated events. While most neutrinos pass through the tank without doing anything, once in a while a neutrino hits an atom in the water, leading to the creation of either an electron (if we have an electron neutrino) or a muon (if we have a muon neutrino).

SNO worked in a similar way, relying on a tank of 1,000 tons of heavy water and about 10,000 light detectors located around the tank. To get an idea about what it looks like, please have a look to the picture below. Whereas the first experiment studied atmospheric neutrinos the latter focused on solar neutrinos. The conclusions of both experiments were very solid: neutrinos oscillate during their propagation. In other words, they change nature during their journey (in space or in media).

[Credits: SNO (CC BY-SA 4.0)]

The above fact is not a real problem in the sense that quantum mechanics allows for it. However, this is only possible if neutrinos are massive, which they are not in the Standard Model. Neutrino masses being a fact, we have thus a contradiction with the Standard Model. Neutrinos are thus one of the best motivations calling for an extension of the Standard Model of particle physics, as already discussed in this earlier blog.

A good way to describe neutrino physics in a manner agnostic to the new phenomena giving rise to the neutrino masses (as we have a plethora of potential model candidates) is to consider a story in which there are three neutrinos different from the Standard Model neutrinos. Here, they are all admixtures of the electron, muon and tau neutrinos of the Standard Model. Each of these neutrinos has a mass, and contains a given amount of each neutrino flavours (a neutrino can be of an electron, a muon or a tau flavour).

It is then up to experiments to measure the neutrino masses and the so-called mixing parameters dictating the flavour content of each neutrino. There are 6 of those parameters, and while some of them start to be measured quite decently, some others are still quite unconstrained. Therefore, neutrino mass models are still living in a grey zone in terms of theory possibilities (and we should not underestimate theorists’ imagination). The experimental constraints are indeed somewhat constraining, but not too drastically. Precision must still come, and it will come!

The mysteries of neutrino physics in a TLDR way

Neutrinos are probably the most interesting beasts of the Standard Model of particle physics. They were postulated initially by Pauli in the 1930s, and considered as a ‘terrible thing’ allowing for an explanation of missing energy signals seen in early radioactivity studies. From that moment, a long journey has been undertaken (and is actually still ongoing).

The Standard Model of particle physics is known to include three species of massless neutrinos, namely the electron neutrino, the muon neutrino and the tau neutrino. The experimental discovery of each of these particles took some time, the tau neutrino having been directly observed only in July 2000. Whilst this was a great success, this came with a lot of intriguing observations.

It indeed appeared that when they undertake long-distance travels, neutrinos of a given (electron, muon or tau) nature can ‘oscillate’ (or be converted) into neutrinos of a different nature. Such a mechanism is quantum mechanically possible, but it requires the three neutrinos to be massive. This is where we have a strong contradiction with the Standard Model. Neutrinos are therefore one of the best portals to physics and new phenomena beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.

As a consequence of neutrino oscillations, each of the three neutrinos is considered as an admixture of the electron neutrino, muon neutrino and tau neutrino of the Standard Model. Equivalently, this means that, each of the three ‘neutrino flavours’ is included by some amount into each of the three neutrinos. The precise measurement of the related parameters is one of the future challenge of all neutrino experiments.

Personally, I started to be interested in such a physics a couple of years ago, and I investigated to which extent the Large Hadron Collider at CERN could help us to unravel a bit the neutrino mysteries. I have proposed, with collaborators, a new handle on the neutrino mixing parameters by means of specific collider probes that have not been considered up to now. This is however the topic of my next blog, hopefully next week.

In the meantime, I wish everybody a nice week, and feel free to abuse of the comment section of this post for questions. Cheers!

Congratulations @lemouth! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s):

Your next target is to reach 300 posts.

Your next payout target is 33000 HP.

The unit is Hive Power equivalent because your rewards can be split into HP and HBD

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out the last post from @hivebuzz:

Anything neutral always creates problems and this is why I dislike fencists :)

If neutrinos are confirmed to not be massless, does it means that the mass of one or two of the standard model particles have been overestimated? This is with respect to the law of conservation of mass.

You should probably start issuing a certificate in particle physics to the readers of your blog. That would be for those that are able to grab and relate with everything.

Thanks for passing by and this comment!

Ahaha! Neutral beasts are indeed hard to detect.

There are two things here.

First, while we can have a viable model with a single massless neutrino, the other two must be massive. Data is very solid about that. However, do we have a massless neutrino and two massive ones, or three massive neutrinos? This is a question we will hopefully be able to answer in a close future. For now, both options are allowed.

Next, there is no such a thing as conservation of mass in particle physics. Only energy (mass being one form of energy) is conserved in any given process. Therefore, mass can be converted in kinetic or potential energy, and vice versa. I am however not too sure about getting the second part of your question right. Do you mind elaborating a little? Thanks!

Rofl! Maybe I could ask @arcange and the @hivebuzz team to create a dedicated badge if they have time. However, I would feel uncomfortable in deciding to who I should give it (although this may be fun).

I assumed all possible conversions have been considered before the mass of particles such as electrons et al were estimated. Now that we are proposing a mass of neutrinos, the mass needs to be accounted for somehow.

I don't know if I making any sense.

If we saw; A + B = 6

and we also say, A+B+C = 6

It means that C = 0, right? Now, if we say that C is not 0, then A+B cannot be equal to 6.

I don't understand your reply... sorry :D

Maybe the clarifying point is that neutrino masses are tiny, but non zero. Therefore, in many phenomena, the precise value has no effect (because it is negligibly small). We need to look at the right observable to get the impact of the mass visible, like neutrino oscillations. There without a mass there is no oscillation whilst with a mass there are oscillations. This cannot be missed.

Yes, that would be fun. Feel free to contact me on Discord or Telegram

Cool! I will do it tonight, when back from work!

https://twitter.com/gentleshaid/status/1490681052079308800

https://twitter.com/A_G_Moore/status/1490924841033101313

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the person sharing the post on Twitter as long as they are registered with @poshtoken. Sign up at https://hiveposh.com.

That is not what I've said !! But it must be difficult to have great artistic skills and great physics jokes (plus an amazing talent for physics vulgarization and clear illustrations)!

I like the idea of "Let's beam a big chunk of metal and see what comes through" ^^

I agree: artistic skills or jokes, a choice has to be made ;)

Yes, this is how it works in practice, more or less (we can additionally use some electromagnetic fields to get rid of any other unwanted particles in our way).

If someone can have both, it's you ;)

It seems that you have put high hopes in me... Hmmm... I will therefore try not to disappoint you ;)

I think physicists must be the most patient people on earth. I was thinking of Marie Curie extracting tiny bits of radium from pitchblende as I read this. At least today's scientists don't run the risk of radiation poisoning (do they?).

A question: because neutrinos have mass, they create a problem (contradiction?) for the standard model. At what point do scientists decide that the standard model might need adjusting? Then, everything else based on the standard model (including predictions about dark matter) might also need adjusting? As you describe it, though, this disruption to you seems exciting because it offers the possibility to make new discoveries, to expand the understanding of the universe (matter?).

Fascinating, @lemouth. I am more familiar with the structure of the atom (than I am with dark matter) because I once did a little research on the Curies, so this was easier for me to read than the dark matter blogs. Still, I think those dark matter blogs have prepared me for some of what appears here--discussion of the Standard Model, for example.

Wow. Another eye-opening blog. I think you will be excited by the work you do for the rest of your life. What a gift.

Thanks, @lemouth, for another great lesson.

Thanks a lot for this interesting comment, to which there are several points to further discuss (and you know how I like discussions ;) ).

A good example of patience is that of the discovery of the top quark.

This particle was postulated in the 1970s, as detailed in this earlier post. Then, in 1977 the bottom quark was discovered at Fermilab. From that moment, physicists were confident about the fact that a sixth quark was lying just behind the corner. The reality was that the top quark was lying behind the next-to-next-to-next corner ;)

At the end of the 1980s, searches at CERN indeed got no result. The top quark should be at least 40 times heavier than the proton. In the meantime, the Tevatron collider at Fermilab started to operate, which resulted in an interesting competition between physicists at CERN and in the US. The bounds quickly rose to 80 times the proton mass.

This coincided with the end of the operations at CERN, so that a second experiment was built at the Tevatron. No competition is indeed no fun... The two experiments around the Tevatron thus competed with each other. In 1992, the lower limit on the mass of the top quark was pushed to 91 times the proton mass, and then to 110 times the proton mass, before finally reaching 130 times the proton mass in almost no time.

In 1994, the first hints for the top quarks appeared (10 events in data, out of trillions of analysed collisions). The top quark was finally discovered in 1995 from about hundreds events. 20 years were needed! See here for more details on this story.

For new phenomena, history seems to repeat again, potentially with a time dilatation factor... who knows? :)

At the moment, we know that the Standard Model is incomplete, but we have no clue about how it should be adjusted. For that reason, we will have to wait so that more signs could emerge from data.

As neutrino masses are tiny, the impact on any non-related item is generally negligible (and factorises from the rest). For instance, neutrinos cannot be dark matter, despite of their non-zero masses. Only specific signals/observables are affected.

I smiled quite a bit after reading the above statement. You indeed refer to my neutrino blog as a blog on the Standard Model, which is what it is to a good extent. However, at the end of the day neutrinos consist of a strong proof that there is some physics beyond the Standard Model somewhere.

Modelling neutrino masses and the associated flavour structure belong definitely to the domain of beyond the Standard Model phenomenology... at least for now (for the reason above-mentioned: we don't know how to extent to Standard Model to accommodate the neutrino masses).

Cheers, and thanks again for the nice questions and comment!

It's like raising a child 😅

I really like the fact that there is no certainty (you will not accept a theory) unless proof can be found and replicated. That may take longer than your lifetime. However much time it takes, though, the integrity of the process is paramount.

Thanks for a great answer, @lemouth.

This will take probably longer than my lifetime.

To introduce some context, I would like to mention that at present time, I make use of a small fraction of my time to work on prospective studies for experiments that may be built after 2035-2040. Whereas I may still be around, I will be in the last part of my career. If we account for delays (as delays are usually happening), I may not even see this happening at all.

This is however how it is. Our experiments are definitely not table-top experiments, and thus require time to be designed, built and operated.

Wonderful and detailed explanation -as usual- of the neutrinos.

I don't think I have any questions about them other than the questions that can't be answered yet.

I'm not very familiar with other valid alternatives, but the standard model seem to need some working on, expansion as you say, or change.

I know nothing has been experimentally verified about supersymmetry, and it's not looking good for it, but from what I understand, it can solve plenty of the problems including the neutrinos mass issue?

Thanks for raising the issue with supersymmetry (I work on supersymmetry from the exact moment I entered the field of particle physics). Supersymmetry (and its minimal incarnation in particular, as this is often what is referred to when supersymmetry is mentioned) is a very popular framework for physics beyond the Standard Model, although other options are getting more and more traction (by virtue of no signal of supersymmetry in data).

However, for what concerns neutrino masses minimal supersymmetry does not help. We indeed need to go beyond the minimal framework so that we have chances to have non-zero neutrino masses. I have personally worked on some interesting models in which we supersymmetrise the Standard Model and generalise in addition the structure of the fundamental interaction. The former allows for all the advantages of a supersymmetric theory, whereas the latter offers a perfect framework for modelling neutrino masses and mixings.

Cheers, and thanks again for this nice and interesting comment.

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more