The Birth of the Ice Age Theory

Chapter IV of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval is entitled Ice. The six sections of this chapter are devoted to the Ice Age, beginning, appropriately enough, with The Birth of the Ice Age Theory. The origins of this theory are intimately connected with the riddle of the erratics, or erratic boulders, a subject Velikovsky addressed in the first section of Chapter II. A few reminders of that discussion would not be out of place here.

An erratic is a rock or boulder that is found in a location where, geologically speaking, it does not belong. If a rock is formed in one place and subsequently transported to another place by a natural—ie non-human—agency, it’s an erratic. Erratics come in all shapes and sizes. The largest known is the Esterhazy megablock in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, which is 38 km long, 30 km wide and up to 100 m thick (Aber, Croot & Fenton 94).

Erratics first entered the scientific literature in the late 18th century when the Swiss geologist and mountaineer Horace-Bénédict de Saussure noticed that the southern slopes of the Jura Mountains were strewn with rocks and boulders of Alpine origin. Saussure believed that these erratics had been transported to their final resting places by water. He briefly considered and dismissed the possibility that they were pyroclasts. The idea that the agent of transport had been ice never occurred to him. The rounded nature of their surfaces was proof in his eyes that water was the culprit.

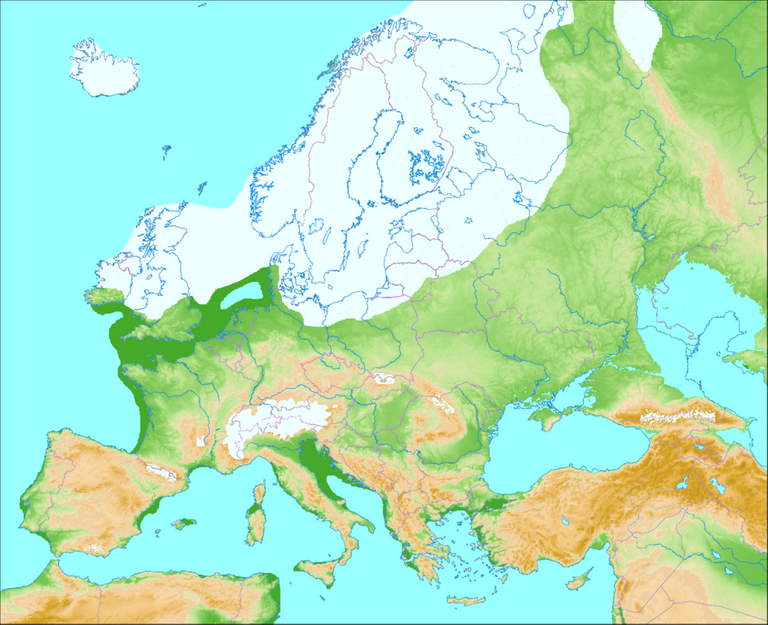

Another large field of erratics was also identified in the North German Plain.

The Scottish geologist James Hutton, it seems, was the first to implicate ice in the transport of erratics in Theory of the Earth (1795). Hutton is often seen as the father of Uniformitarianism and the discoverer of deep time. Since his day the problem of erratics has remained a ground of contention between catastrophists and gradualists.

In Chapter II of Earth in Upheaval, Velikovsky simply established the existence of erratic boulders, without drawing any conclusions. He did not argue that Saussure’s explanation of how they were transported to their final resting places—by cataclysmic floods—must be the right one. Nor did he even mention the competing hypotheses of Hutton and his gradualist disciples. It was only in Chapter IV that he addressed these questions.

The Theory of the Ice Age

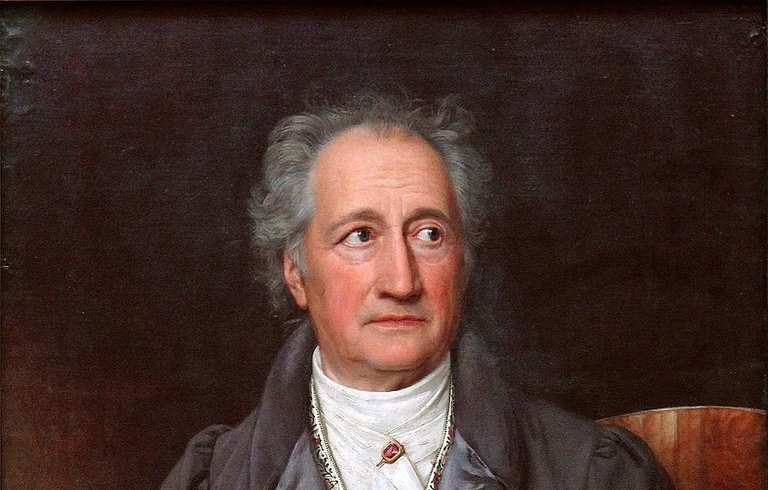

The geological term erratic entered the scientific lexicon quite late. According to Richard Foster Flint, a gradualist professor of geology at Yale University, it was derived from Jean de Charpentier, who characterized the southern slopes of the Jura Mountains as terrain erratique on account of the abundance of boulders found there that were clearly of Alpine origin. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the word to 1828—thirteen years before Charpentier—but Charpentier himself gave the credit to the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe’s progressive idea of a European Ice Age can be found in the second edition of his fourth novel, Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre (1829). He first broached the idea, however, in seven short scientific fragments: Herrn von Hoffs geologisches Werk [The Geological Work of Karl Von Hoff], written in 1823 and named for the Father of German Uniformitarianism, and six short papers from 1829-30, to two of which his editors later gave the titles Erratische Blöcke [Erratic Boulders] and Eiszeit [Ice Age] (Cameron 751-754).

Goethe was the true father of the Ice Age Theory, though he has been largely written out of the story. He is not even mentioned by Flint, who gives most of the credit to men like Ignaz Venetz, Jean de Charpentier and Louis Agassiz. But Charpentier and Agassiz both acknowledged Goethe’s priority and the influence he had on their own ideas. It is curious, then, that Velikovsky fails to mention Goethe or to recognize his contributions to the theory. Instead, he gives the credit to A Bernardi, a teacher in a forestry school in the Netherlands, and the German botanist Karl Friedrich Schimper, who coined the term Eiszeit.

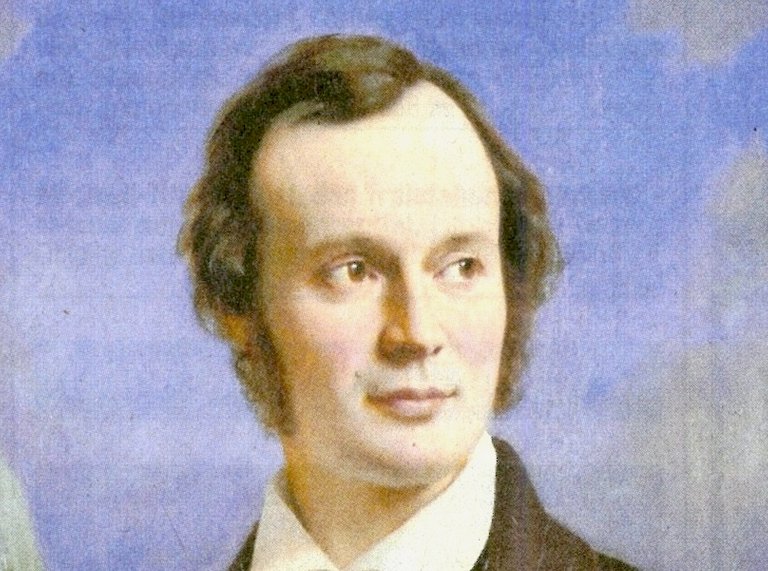

Louis Agassiz

The Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz is generally credited with drawing together all the disparate notions of ancient glaciology that were floating around in the 1830s and creating a fully-fledged Ice Age Theory from them. Initially a skeptic, he became a passionate adherent of the idea of a recent Ice Age. Between 1837, when he presented his paper Discours sur l’ancienne extension des glaciers before the Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, and 1840, when he published his Études sur les glaciers, he worked tirelessly to promote the new theory, numbering the influential British geologists William Buckland and Charles Lyell among his converts. In 1846 he moved to the United States, where he continued to promote the Ice Age Theory.

As Velikovsky notes, the Ice Age Theory has won converts to its cause from the ranks of both the Catastrophists and the Uniformitarians. The latter saw it as a way to explain phenomena such as erratics without having recourse to catastrophic floods—whether Biblical or not—sweeping across entire continents and overtopping mountain ranges, while catastrophists argued that the onset and termination of an ice age could only be explained by a sudden and catastrophic alteration in the Earth’s climate.

Agassiz himself incorporated catastrophist ideas into his nascent theory, some of them quite extreme, which embarrassed many of his gradualist supporters. He believed, for example, that the onset of the Ice Age had been sudden and that the Alps had risen to their current height at the end of the Ice Age:

Now, as it has been shown that the mammoth-bearing ice existed anterior to the rise of the Alps—since the strata bearing fossils of elephas primigenius, which were contemporaneous with the ice that Kotzebue called primitive, were dislodged during the rise of the Alps—I conclude that there was then a sheet of ice on European soil, which prevented the complete removal of the deposits, and the filling in of the lakes and of all the basins existing then or formed by the rise of the Alps. This sheet of ice must have extended as far as the erratic blocks ... The surface of Europe, previously adorned with tropical vegetation and inhabited by herds of large elephants, enormous hippopotami, and gigantic carnivores, was suddenly buried under a vast mantle of ice, covering alike the plains, lakes, seas, and plateaus. (Agassiz 1840:313-314)

Agassiz also believed that the end of the Ice Age was catastrophic and volcanic:

But this state of affairs came to an end, and a reaction set in; the fluid masses in the interior of the Earth boiled over once again with great intensity; their action could be felt in the direction of the principal chain of the Alps, whose rocks were altered in divers manner and raised to their present height, with the crust of ice that covered them ... However, the appearance of the Alpine chain had suddenly modified the climatic conditions of Switzerland, the temperature had increased and the alternation of the seasons, in making itself felt once again, must have established continual oscillations of heat and cold which have necessarily imprinted on the ice of those times oscillations similar to those experienced by glaciers today. (Agassiz 314-315)

As we have just seen, at least the latter, that is to say, [the surface of the Earth] which immediately preceded the appearance of Man, had been buried in ice before the chain of the central Alps was raised, and that the cold which produced this ice must have been instantaneous to preserve, as it did, the carcasses of the elephants that once inhabited Siberia. (Agassiz 327)

Of course, these ideas are dismissed by today’s gradualist mainstream, who believe that the Alps have been rising slowly to their present height for over 60 million years and that the Pleistocene Ice Age operated over a period of about two million years:

One of Agassiz’s weak points was his inclination to indulge in wild speculations on subjects about which he knew very little. (Carozzi 64)

Although Agassiz’s hypothesis that the Ice Age had preceded the uplifting of the Alps was controversial, he was not prepared to abandon it, and he repeated it in the final chapter of his Études sur les glaciers of 1840. The reaction of the British geologist and clergyman Adam Sedgwick was typical for the time:

I have read his Ice-book. It is excellent, but in the last chapter he loses his balance, and runs away with the bit in his mouth. (Carozzi 72)

Erratics Again

Before the birth of the Ice Age Theory, gradualists like Charles Lyell had suggested that erratics had been transported to their resting places by icebergs and ice rafts:

Effects of ice in removing stones.—In mountainous regions and high northern latitudes, the moving of heavy stones by water is greatly assisted by the ice which adheres to them, and which, forming together with the rock a mass of less specific gravity, is readily borne along ...

In northern latitudes, where glaciers descend into valleys terminating in the sea, great masses of ice, on arriving at the shore, are occasionally detached and floated off together with their “moraine.” The currents of the ocean are then often instrumental in transporting them to great distances. Scoresby counted 500 icebergs drifting along in latitude 69° and 70° north, which rose above the surface from the height of one to two hundred feet, and measured from a few yards to a mile in circumference. Many of these contained strata of earth and stones, or were loaded with beds of rock of great thickness, of which

the weight was conjectured to be from fifty thousand to one hundred thousand tons. Such bergs must be of great magnitude; because the mass of ice below the level of the water is between seven and eight times greater than that above. Wherever they are dissolved, it is evident that the “moraine” will fall to the bottom of the sea. In this manner may submarine valleys, mountains, and platforms become strewed over with scattered blocks of foreign rock, of a nature perfectly dissimilar from all in the vicinity, and which may have been transported across unfathomable abysses. We have before stated, that some ice islands have been known to drift from Baffin’s Bay to the Azores, and from the South Pole to the immediate neighbourhood of the Cape of Good Hope. (Lyell 255 ... 256-257)

Another hypothesis, which I first came across in the The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: Volume 1 while researching this article, is that erratics were transported by glaciers piggy-back fashion, while the glaciers themselves were transported by floods:

In all discussions on this subject it should be remembered, that the present glaciers are covered by huge blocks which fall from the heights upon them, and that if these glaciers were floated and carried down by a great body of water through the valleys opened to them, the blocks might become scattered as we now find them.

The Ice Age Theory provided gradualists with an altogether more plausible means of transport. But even today’s gradualists acknowledge that the transportation of the larger erratics still represents an unsolved conundrum. Was the Esterhazy Megablock picked up by an ice sheet and carried to its final resting place? James Aber, who discovered and named the Esterhazy Megablock, believes this is a theoretical possibility, but the mechanism he suggests remains speculative and unproven:

The megablock may not have moved far, perhaps less lateral displacement than its own width, in order to produce the observed structures. The only conceivable means of displacing a megablock of such huge size was by freezing onto the bottom of an overriding ice sheet, in which case the megablock became the basal layer of the ice sheet. It is highly improbable that this megablock could have been pushed in front of an advancing glacier. Subglacial sliding of permafrozen material over a thawed, clay-rich substratum seems to be the most likely explanation for displacement of the Esterhazy megablock. (Aber & Ber 104)

References

- James S Aber, David G Croot, Mark M Fenton, Glaciotectonic Landforms and Structures, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (1989)

- James S Aber, Andrzej Ber, Glaciotectonism, in Jaap J M van der Meer (editor), Developments in Quaternary Science, Volume 6, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2007)

- Louis Agassiz, Discours de Neuchâtel, Actes de la Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, Band 22, pp v-xxxii, Petitpierre, Neuchâtel (1837)

- Louis Agassiz, Études sur les glaciers, Jent and Gassmann, Neuchatel (1840)

- Dorothy Cameron, Early Discoverers XXII: Goethe – Discoverer of the Ice Age, Journal of Glaciology, Volume 5, Issue 41, pp 751-754, Glaciological Society, Cambridge (1965)

- Albert V Carozzi, Agassiz’s Amazing Geological Speculation: The Ice-Age, Studies in Romanticism, Volume 5, Number 2 (Winter 1966), pp 57-83, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD (1966)

- Jean de Charpentier, Essai sur les glaciers et sur le terrain erratique du bassin de Rhône, Marc Ducloux, Lausanne (1841)

- Richard Foster Flint, Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York (1947)

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Zur Naturwissenschaft überhaupt, Mineralogie und Geologie 1, Goethes Werke, II. Abteilung, Band 9, Hermann Böhlau, Weimar (1892)

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Zur Naturwissenschaft überhaupt, Mineralogie und Geologie 2, Goethes Werke, II. Abteilung, Band 10, Hermann Böhlau, Weimar (1892)

- James Hutton, Theory of the Earth, with Proofs and Illustrations, Volume II, William Creech, Edinburgh (1795)

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, Volume 1, Third Edition, John Murray, London (1835)

- Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, Voyages dans les Alpes, Volume I, Barde, Manget & Comp, Geneva (1786)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- The Last Glacial Maximum in Europe: © Ulamm, Creative Commons License

- Pierre à Martin: Wikimedia Commons, © Björn S, Creative Commons License

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Joseph Karl Stieler (artist), Neue Pinakothek, Munich, WAF 1048, Public Domain

- Louis Agassiz: Fritz Zuber-Bühler (artist), Public Domain

- Motte Stone: An Erratic Boulder in County Wicklow: © David Quinn, Creative Commons License