On the Russian Plains

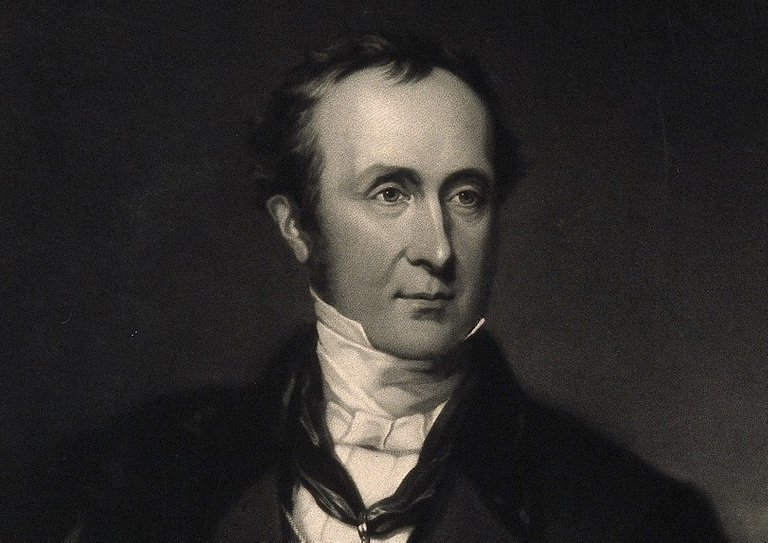

Chapter IV, Part 2 of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval is called On the Russian Plains. In this section, Velikovsky reviews the groundbreaking geological work carried out by the Scottish geologist Roderick Impey Murchison in Russia in the 1840s. On this expedition, Murchison discovered a new geological system, which he called the Permian after the Perm region of Russia, which lies about 1000 km to the east of Moscow, near the Ural Mountains. The result of this labour was a two volume work on the geology of European Russia and the Ural Mountains that runs to almost 1500 pages.

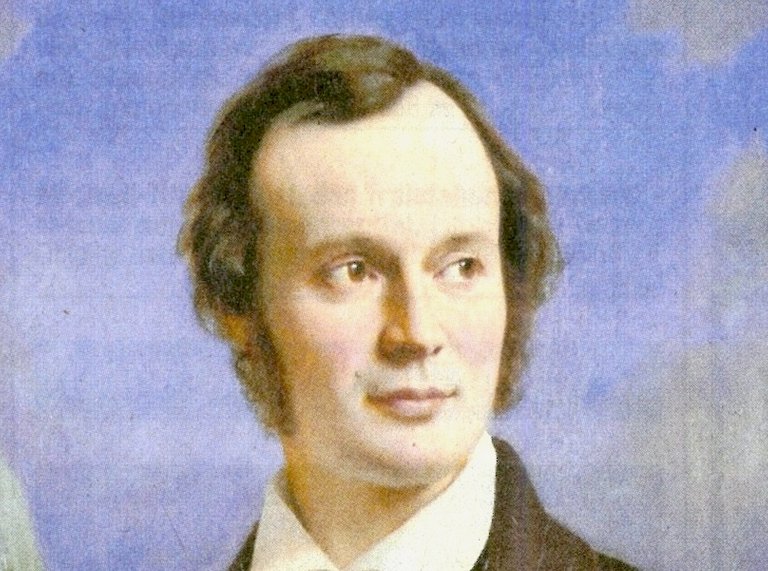

Murchison was a progressive creationist. He rejected all forms of evolution, believing instead that God created new species over periods of hundreds of millions of years. In the previous article, we saw how Louis Agassiz, one of the principal architects of the Ice Age Theory, visited Britain to promote the new doctrine. Agassiz was particularly keen to convert William Buckland and Roderick Murchison, two of Britain’s leading geologists, to the cause. He succeeded in winning over William Buckland, and he also netted Charles Lyell along the way, but Murchison remained unmoved.

Murchison had earlier contributed to the discovery of the Silurian and Devonian Systems, but it was his work on the erratics in the eastern part of the Europe that Velikovsky is most interested in.

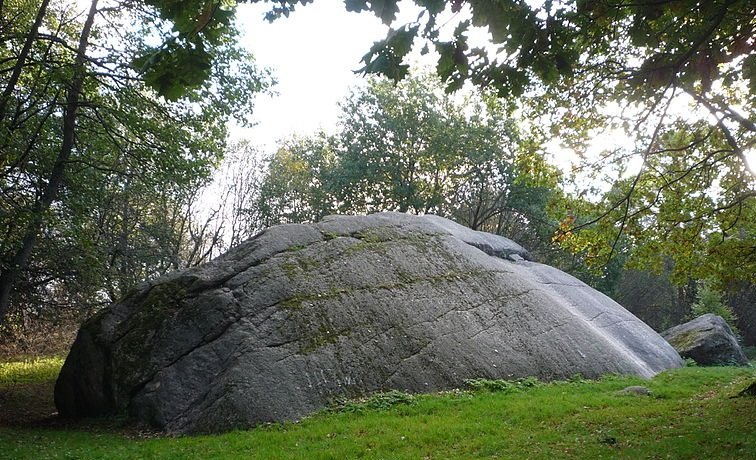

Erratics

In the early 1840s, Murchison studied the fields of erratic blocks strewn across the East European Plain and in the Carpathian Mountains. He remained convinced that these erratics had been transported from Scandinavia to their final resting places by liquid water—not ice—though he did concede that some of the larger erratics may have been transported by icebergs floating in a sea that formerly covered this land. He was particularly impressed by the fact that the erratics decreased in both size and number the farther one traced them from their place of origin:

The drift of Russia and Germany, in common with that of England, exhibits, for the most part, a diminution in the quantity and size of the blocks, the further they have ranged from the source of their origin. Hence, in the parallel of Moscow, to which place and far beyond they extend, the fragments of granite and greenstone seldom exceed two or three feet in diameter; whilst near St. Petersburg their diameter is often as many yards. In pass from the White Sea to Nijni Novgorod, the same facts present themselves ... The traveller ... the more he extends his survey, the more he will find, that all these accumulations and their associated blocks are parts of one great system of operations, and that they have all been formed in one long period of time. He will also be convinced, that the widely-spread and finely laminated sands cannot have been accumulated except under water; and when he sees these sands and gravel, as on the Vaga, overlie strata replete with pleistocene or modern marine shells before described, he will conclude with us, that this great northern drift (by whatever power transported) was deposited on the bottom of a sea ... there is no doubt in our minds, that the whole of that portion of the continent was beneath the waters, at the period of the distribution of the blocks. (Murchison 1845:523-524)

Murchison considered glaciers and ice sheets inadequate as forms of transport. This left only two alternatives to his mind:

[There] are, it appears to us, only two methods of accounting for such far-borne detritus. One of these is the action of drift, by which fragments of mountain chains, dissevered from their parent masses at periods of disturbance and oscillation, have been transported to great distances by powerful currents of water; the other, the floating away of ice islands from the edges of chains, formerly encompassed by sea-advancing glaciers, which isles, after sailing in certain directions, have dropped their loads on the bottom of the sea; that sea bottom on which the blocks are distributed having been since raised into the dry land. (Murchison 1845:528)

In order to transport blocks of such a size and in such quantities as were to be found in the East European Plain, the waves and currents must have been occasioned by relative and often paroxysmal changes of the level of sea and land (Murchison 1845:553).

Later Years

In his old age, Murchison conceded that the Ice Age of Agassiz had been a reality, but he still maintained that ice could not account for the fields of erratics found in Russia and eastern Europe. Velikovsky writes:

In his later years, Murchison, without retracting any of his observations and conclusions made in Russia, admitted in a letter to Agassiz that he regretted his early opposition to the Ice Age theory. On the other hand, marine deposits of recent age were found in large areas of European and Asiatic Russia. In the Caspian Sea, which stretches between southern Russia and Persia, live seals related to the seals of the Arctic Ocean. It is concluded that the polar sea spread and established a connection with the Caspian Sea, and this in Recent time. (Velikovsky 36)

Velikovsky does not identify this letter or cite any source for it. Apparently, it was written in 1862:

Twenty years later [ie 1862], with rare candor, Murchison wrote to Agassiz as follows ... “I send you my last anniversary address, which I wrote entirely myself; and I beg you to believe that in the part of it that refers to the glacial period, and to Europe as it was geographically, I have had the sincerest pleasure in avowing that I was wrong in opposing as I did your grand and original idea of my native mountains. Yes! I am now convinced that glaciers did descend from the mountains to the plains as they do now in Greenland.” (Agassiz 341)

Velikovsky instead follows the paragraph quoted above with a quotation from George D Hubbard’s The Geography of Europe of 1937:

“Since the ice withdrew, the Arctic Ocean has spread over large areas of northern Russia and in many places has left marine deposits on the glacial drift as well as on the firmer rocks. The Arctic water spread also over the Obi Basin far to the south and established connections with the Caspian Sea, at which time the progenitors of the present seals of the Caspian rocky islands migrated thither to become stranded when the waters withdrew.” (Velikovsky 36)

The final edition of Hubbard’s work was published in 1952. It is surprising to find a mainstream geologist asserting in the middle of the 20th century that the Arctic Ocean and Caspian Sea were connected in post-glacial times (Hubbard 22). Today’s geomorphologists believe that the flooding of the land between the Arctic Ocean and the Caspian Sea occurred between 1.5 and 1 million years ago, at the end of a much earlier glaciation (Huseynov).

Carpathian Erratics

The lowlying land in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains of Eastern Europe is also strewn with erratic boulders. Murchison identified these erratics as being of Scandinavian provenance. If this is true, then glaciologists may be hard pressed to explain how ice could have transported them so far south. Did the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet ever reach this far south? And are these erratics truly of Scandinavian provenance?

The answer to both questions appears to be Yes. Although the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet probably did not extend further south than latitude 52° N during the last glaciation (known locally as the Weichsel Glaciation), it is thought to have reached considerably further than this during the earlier Elster and Saale Glaciations:

The maximum advance of the ice sheet in North Germany during the Drenthe Stage is described by a line from Düsseldorf via Paderborn, Hamelin, Goslar, Eisleben, Zeitz and Meissen to Görlitz. From the eastern edge of the Harz eastwards (Poland, Brandenburg, Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt) the ice advanced to about 10 to 50 km behind the maximum extent of the Elster glaciation. On the northern edge of the Harz the two ice sheets reached the same line; and west of the Harz the ice of the Saale complex extended over 100 km further south than the ice sheet of the Elster ... The Drenthe Stage corresponds to the maximum extent of glaciation during the Saale complex. (Wikipedia)

In 2013, two geologists, Leszek Lindner & Leszek Marks, investigated the origin and age of Pleistocene ‘mixed gravels’ in the northern foreland of the Carpathians. Lindner and Marks concede that these mixed gravels contain material of both local and Scandinavian origin:

Accumulations of pebbles in the northern foreland of the Carpathians in Ukraine and Poland, composed mostly of Carpathian sandstones, but with a small admixture of Scandinavian rocks, have been known for many years as the ‘mixed gravels’. (Lindner & Marks 29)

The authors believe that the ice sheet first transported the Scandinavian material into the East European Plain and deposited it in the neighbourhood of the Carpathians. This material, together with material eroded from local flysch, was then redeposited by a combination of fluvial and glacial mechanisms during late-glacial or interglacial periods:

All of the data presented suggest most convincingly that the mixed gravels are mostly of fluvial, partly fluvio-periglacial and partly interglacial origin. Deposition of these gravels occurred usually to the north of the areas with in situ occurrences of rocks of the Carpathian flysch, that is, to the north of the Carpathian nappes (Fig. 5). Predominance of Carpathian over Scandinavian material in these gravels proves unequivocally the prevailing role of the Carpathian rivers. When flowing from the south northwards, they first eroded flysch rocks and then the accumulations of freshly deposited glacial deposits. (Lindner & Marks 33-34)

The evidence, therefore, does not rule out the possibility that the Carpathian erratics are ultimately of glacial origin.

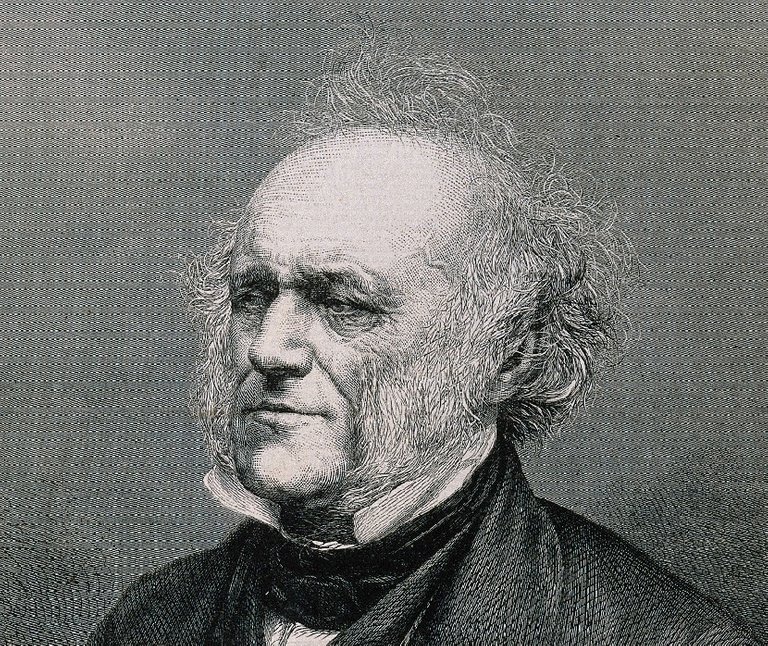

But what of Murchison’s observation that the erratic boulders strewn across the Russian Plain exhibit a gradual diminution in their size and number as one proceeds south? Does this not confirm his hypothesis that they were water-borne? Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any modern studies that investigate this phenomenon. In the 1850s, however, Charles Lyell conceded this point and cited it in favour of his hypothesis that erratics were distributed by icebergs:

It was stated that in Russia the erratics diminished generally in size in proportion as they are traced from their source ... This phenomenon is in perfect harmony with the theory of ice-islands floating in a sea of variable depth; for the heavier erratics require icebergs of a larger size to buoy them up; and, even when there are no stones frozen in, more than seven eighths, and often nine tenths, of a mass of drift ice is under water. The greater, therefore, the volume of the iceberg, the sooner it would impinge on some shallower part of the sea; while the smaller and lighter floes, laden with finer mud and gravel, may pass freely over the same banks, and be carried to much greater distances. (Lyell 130)

Anniversary Address

In 1866, when he was seventy-four years old, Murchison delivered an address to the Royal Geographical Society in London on the occasion of its Anniversary Meeting on 28 May. In the course of this address, he had occasion to discuss, among many other matters, the continuing progress of the controversy between Catastrophism and Uniformitarianism. Murchison remained a catastrophist to his dying day, but in this address he strikes a more conciliatory note:

In speaking of Uniformitarians ... whose leader is my eminent friend Lyell, the worthy inheritor of the mantle of Hutton and Playfair, let it not be supposed that any reasonable geologist, certainly not myself, who may dwell upon the great and sudden dislocations which he believes the crust of the earth underwent from time to time in far bygone periods, is not also a strenuous advocate of uniformity of causation as respects the enormously long and undisturbed periods required to account for the accumulation of the thick sedimentary deposits. On the other hand, unbiased Uniformitarians now admit of occasional catastrophic action; and, as the question is thus reduced to be one of degree only—that degree to be fairly gauged by measuring the relations and extent of the ruptures of the crust of the earth—I feel confident that out of fair discussion the exact truth will ultimately be obtained. (Murchison 1866:cxxiv-cxxv)

More than one-and-a-half centuries later, we are still searching for that exact truth.

References

- Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz, Louis Agassiz: His Life and Correspondence, Volume 1, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston (1886)

- George David Hubbard, The Geography of Europe, Second Edition, Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc, New York (1947)

- Said Huseynov, Fate of the Caspian Sea, Natural History Magazine, Research Triangle Park NC (2011-2012)

- Leszek Lindner & Leszek Marks, Carpathian and Scandinavian Erratics, Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae, Volume 83, pp 29-36, Geological Society of Poland, Warsaw (2013)

- Charles Lyell, A Manual of Elementary Geology, Fifth Edition, John Murray, London (1855)

- Roderick Impey Murchison, The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1845)

- Roderick Impey Murchison, Address to the Royal Geographical Society, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Volume 36, pp cxviii-cxcvii, John Murray, London (1866)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- Roderick Impey Murchison: W Walker (engraver), © Wellcome Images, Creative Commons License

- Kabelikivi Erratic in Estonia: © Jaan Rebane, Creative Commons License

- Louis Agassiz: Fritz Zuber-Bühler (artist), Public Domain

- Erratic the Pietroasa Valley (Rodnei Mountains): © Petru Urdea, Fair Use

- Maximum Extent of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet: Botaurus, Public Domain

- Charles Lyell: Murden (engraver), © Wellcome Images, Creative Commons License

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and reblogged by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here