Darwin in South America

In “Darwin in South America”, the final section of Chapter III of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval, Velikovsky takes a brief look at Charles Darwin’s reaction to the evidence of widespread extinction in the fossil record.

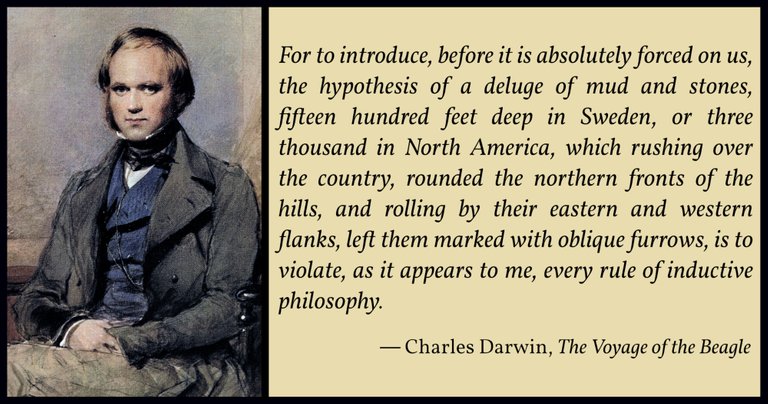

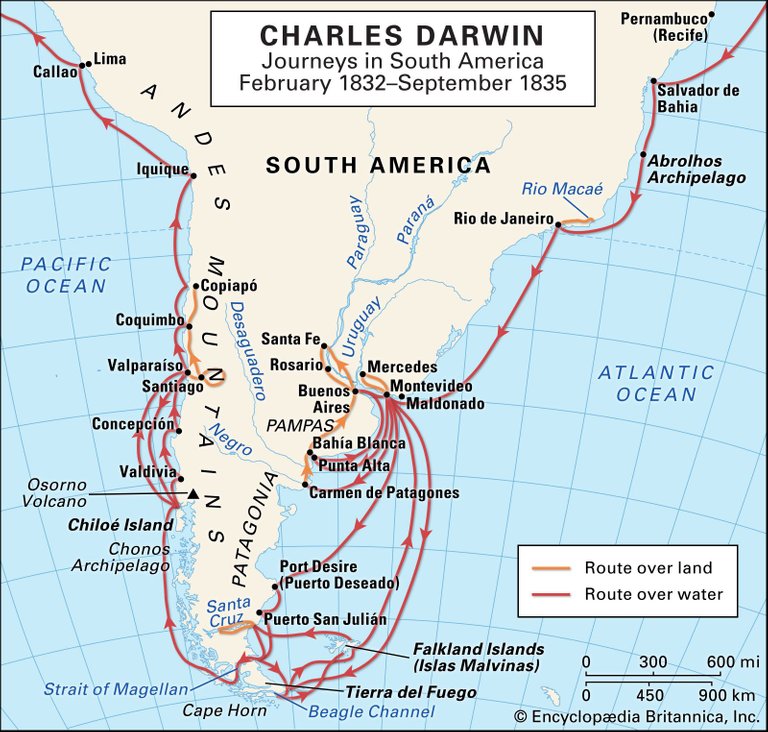

In the study of geology and palaeontology, Darwin’s only experience in the field was the period he spent as a naturalist aboard HMS Beagle (1831-36). Beagle’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, had presented the 22-year-old Darwin with a copy of the first volume of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which was then newly published. FitzRoy was himself an amateur geologist and, according to some accounts, he was anxious to secure the services of a naturalist who shared his scientific interests and could dine with him as an equal—in other words, a gentleman companion. The Principles of Geology was intended to be a welcoming gift.

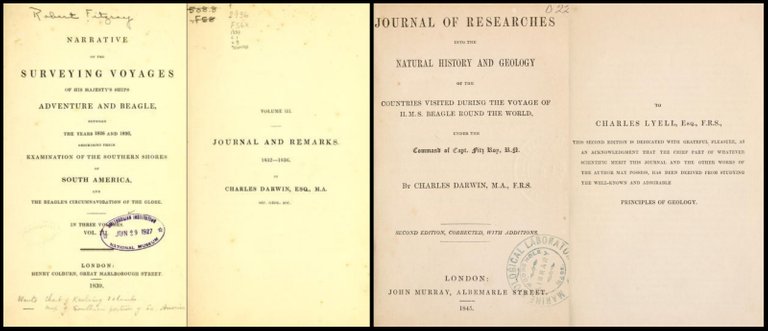

This influential book became Darwin’s New Testament. The Uniformitarian views espoused in its pages gradually took possession of his mind and coloured his observations, which he documented in a journal. This was published in 1839 as the third volume of Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle. Today, it is better known as The Voyage of the Beagle. Its commercial success made Darwin a household name. Darwin dedicated the second edition of this work to Charles Lyell, who had become a close friend.

Robert FitzRoy was a Biblical Literalist. He later retracted his support for Lyell’s Uniformitarianism and even included some remarks on Noah’s Flood in Volume 2 of the Beagle Narratives. Darwin, however, never regretted coming under the influence of Lyell’s teachings. But he must have been hard-pressed to explain some of the things he observed during the voyage without diluting Lyell’s Uniformitarianism. Velikovsky quotes from his entry of 9 January 1834:

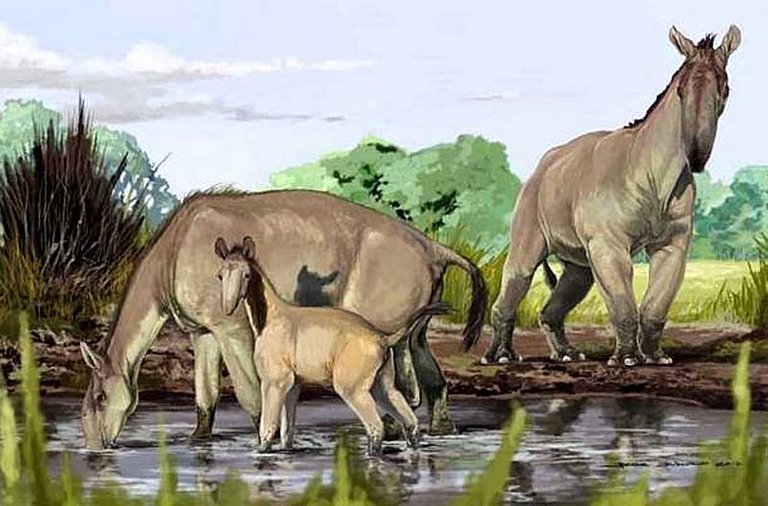

It is impossible to reflect on the changed state of the American continent without the deepest astonishment. Formerly it must have swarmed with great monsters: now we find mere pigmies, compared with the antecedent, allied races. If Buffon had known of the gigantic sloth and armadillo-like animals, and of the lost Pachydermata, he might have said with a greater semblance of truth that the creative force in America had lost its power, rather than that it had never possessed great vigour. The greater number, if not all, of these extinct quadrupeds lived at a late period, and were the contemporaries of most of the existing sea-shells. Since they lived, no very great change in the form of the land can have taken place. What, then, has exterminated so many species and whole genera? The mind at first is irresistibly hurried into the belief of some great catastrophe; but thus to destroy animals, both large and small, in Southern Patagonia, in Brazil, on the Cordillera of Peru, in North America up to Behring’s Straits, we must shake the entire framework of the globe. (Darwin 1845:173-174)

Velikovsky cuts Darwin off at this point, but the passage continues (sections in bold are those that Velikovsky subsequently quotes):

An examination, moreover, of the geology of La Plata and Patagonia, leads to the belief that all the features of the land result from slow and gradual changes. It appears from the character of the fossils in Europe, Asia, Australia, and in North and South America, that those conditions which favour the life of the larger quadrupeds were lately co-extensive with the world: what those conditions were, no one has yet even conjectured. It could hardly have been a change of temperature, which at about the same time destroyed the inhabitants of tropical, temperate, and arctic latitudes on both sides of the globe. In North America we positively know from Mr. Lyell, that the large quadrupeds lived subsequently to that period, when boulders were brought into latitudes at which icebergs now never arrive: from conclusive but indirect reasons we may feel sure, that in the southern hemisphere the Macrauchenia, also, lived long subsequently to the ice-transporting boulder-period. Did man, after his first inroad into South America, destroy, as has been suggested, the unwieldy Megatherium and the other Edentata? We must at least look to some other cause for the destruction of the little tucutuco at Bahia Blanca, and of the many fossil mice and other small quadrupeds in Brazil. No one will imagine that a drought, even far severer than those which cause such losses in the provinces of La Plata, could destroy every individual of every species from Southern Patagonia to Behring’s Straits. What shall we say of the extinction of the horse? Did those plains fail of pasture, which have since been overrun by thousands and hundreds of thousands of the descendants of the stock introduced by the Spaniards? Have the subsequently introduced species consumed the food of the great antecedent races? Can we believe that the Capybara has taken the food of the Toxodon, the Guanaco of the Macrauchenia, the existing small Edentata of their numerous gigantic prototypes? Certainly, no fact in the long history of the world is so startling as the wide and repeated exterminations of its inhabitants.

Nevertheless, if we consider the subject under another point of view, it will appear less perplexing. “We do not steadily bear in mind, how profoundly ignorant we are of the conditions of existence of every animal; nor do we always remember, that some check is constantly preventing the too rapid increase of every organized being left in a state of nature. The supply of food, on an average, remains constant; yet the tendency in every animal to increase by propagation is geometrical; and its surprising effects have nowhere been more astonishingly shown, than in the case of the European animals run wild during the last few centuries in America. Every animal in a state of nature regularly breeds; yet in a species long established, any great increase in numbers is obviously impossible, and must be checked by some means. We are, nevertheless, seldom able with certainty to tell in any given species, at what period of life, or at what period of the year, or whether only at long intervals, the check falls; or, again, what is the precise nature of the check. Hence probably it is, that we feel so little surprise at one, of two species closely allied in habits, being rare and the other abundant in the same district; or, again, that one should be abundant in one district, and another, filling the same place in the economy of nature, should be abundant in a neighbouring district, differing very little in its conditions. If asked how this is, one immediately replies that it is determined by some slight difference in climate, food, or the number of enemies: yet how rarely, if ever, we can point out the precise cause and manner of action of the check! We are, therefore, driven to the conclusion, that causes generally quite inappreciable by us, determine whether a given species shall be abundant or scanty in numbers. (Darwin 1845:174-175)

Velikovsky’s selective quotations leave the reader with the impression that Darwin was greatly perplexed by the evidence and despaired of accounting for it without invoking some form of Catastrophism. But nothing could be further from the truth. Darwin clearly believed that the evidence was entirely consistent with Lyell’s principles:

In the cases where we can trace the extinction of a species through man, either wholly or in one limited district, we know that it becomes rarer and rarer, and is then lost: it would be difficult to point out any just distinction between a species destroyed by man or by the increase of its natural enemies. The evidence of rarity preceding extinction, is more striking in the successive tertiary strata, as remarked by several able observers; it has often been found that a shell very common in a tertiary stratum is now most rare, and has even long been thought to be extinct. If then, as appears probable, species first become rare and then extinct—if the too rapid increase of every species, even the most favoured, is steadily checked, as we must admit, though how and when it is hard to say—and if we see, without the smallest surprise, though unable to assign the precise reason, one species abundant and another closely-allied species rare in the same district—why should we feel such great astonishment at the rarity being carried a step further to extinction? An action going on, on every side of us, and yet barely appreciable, might surely be carried a little further, without exciting our observation. Who would feel any great surprise at hearing that the Megalonyx was formerly rare compared with the Megatherium, or that one of the fossil monkeys was few in number compared with one of the now living monkeys? and yet in this comparative rarity, we should have the plainest evidence of less favourable conditions for their existence. To admit that species generally become rare before they become extinct—to feel no surprise at the comparative rarity of one species with another, and yet to call in some extraordinary agent and to marvel greatly when a species ceases to exist, appears to me much the same as to admit that sickness in the individual is the prelude to death—to feel no surprise at sickness—but when the sick man dies to wonder, and to believe that he died through violence. (Darwin 1834:175-176)

Velikovsky quotes from the original edition of the work, which was published in 1839. A revised edition was published in 1845 as Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World. This differs from the original edition in many details. The most significant change, however, is the removal from these extracts of anything that might be considered Catastrophist:

It is impossible to reflect without the deepest astonishment, on the changed state of this continent. Formerly it must have swarmed with great monsters, like the southern parts of Africa, but now we find only the tapir, guanaco, armadillo, and capybara; mere pigmies compared to the antecedent races. The greater number, if not all, of these extinct quadrupeds lived at a very recent period; and many of them were contemporaries of the existing molluscs. Since their loss, no very great physical changes can have taken place in the nature of the country. What then has exterminated so many living creatures? In the Pampas, the great sepulchre of such remains, there are no signs of violence, but on the contrary, of the most quiet and scarcely sensible changes. At Bahia Blanca I endeavoured to show the probability that the ancient Edentata, like the present species, lived in a dry and sterile country, such as now is found in that neighbourhood. With respect to the camel-like llama of Patagonia, the same grounds which, before knowing more than the size of the remains, perplexed me, by not allowing any great change of climate, now that we can guess the habits of the animal, are strangely confirmed. What shall we say of the death of the fossil horse ? Did those plains fail in pasture, which afterwards were overrun by thousands and tens of thousands of the successors of the fresh stock introduced with the Spanish colonist? In some countries, we may believe, that a number of species subsequently introduced, by consuming the food of the antecedent races, may have caused their extermination; but we can scarcely credit that the armadillo has devoured the food of the immense Megatherium, the capybara of the Toxodon, or the guanaco of the camel-like kind. But granting that all such changes have been small, yet we are so profoundly ignorant concerning the physiological relations, on which the life, and even health (as shown by epidemics) of any existing species depends, that we argue with still less safety about either the life or death of any extinct kind.

One is tempted to believe in such simple relations, as variation of climate and food, or introduction of enemies, or the increased numbers of other species, as the cause of the succession of races. But it may be asked whether it is probable than any such cause should have been in action during the same epoch over the whole northern hemisphere, so as to destroy the Elephas primigenius, on the shores of Spain, on the plains of Siberia, and in Northern America; and in a like manner, the Bos urus, over a range of scarcely less extent ? Did such changes put a period to the life of Mastodon angustidens, and of the fossil horse, both in Europe and on the Eastern slope of the Cordillera in Southern America? If they did, they must have been changes common to the whole worlds such as gradual refrigeration, whether from modifications of physical geography, or from central cooling. But on this assumption, we have to struggle with the difficulty that these supposed changes, although scarcely sufficient to affect molluscous animals either in Europe or South America, yet destroyed many quadrupeds in regions now characterized by frigid, temperate, and warm climates! These cases of extinction forcibly recal the idea (I do not wish to draw any close analogy) of certain fruit-trees, which, it has been asserted, though grafted on young stems, planted in varied situations, and fertilized by the richest manures, yet at one period, have all withered away and perished. A fixed and determined length of life has in such cases been given to thousands and thousands of buds (or individual germs), although produced in long succession. Among the greater number of animals, each individual appears nearly independent of its kind; yet all of one kind may be bound together by common laws, as well as a certain number of individual buds in the tree, or polypi in the Zoophyte.

I will add one other remark. We see that whole series of animals, which have been created with peculiar kinds of organization, are confined to certain areas; and we can hardly suppose these structures are only adaptations to peculiarities of climate or country; for otherwise, animals belonging to a distinct type, and introduced by man, would not succeed so admirably, even to the extermination of the aborigines. On such grounds it does not seem a necessary conclusion, that the extinction of species, more than their creation, should exclusively depend on the nature (altered by physical changes) of their country. All that at present can be said with certainty, is that, as with the individual, so with the species, the hour of life has run its course, and is spent. (Darwin 1845:210-212)

Darwin has censored himself, removing from the revised edition any mention of the shaking of the entire framework of the globe. Perhaps Velikovsky was right after all, and Darwin was embarrassed by the evidence. If so, then Velikovsky’s concluding remark is justified:

Out of Darwin’s embarrassment grew the idea of extinction of species as a prelude to natural selection. (Velikovsky 30)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Charles Darwin, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the Years 1826 and 1836, Volume 3, Henry Colburn, London (1839)

- Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, Second Edition, John Murray, London (1845)

- Robert Fitzroy, Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the Years 1826 and 1836, Volume 2, Henry Colburn, London (1839)

- Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1830)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- HMS Beagle in the Galápagos: John Chancellor (artist), © Gordon Chancellor, Fair Use

- Charles Darwin (1840): George Richmond (artist), Darwin Museum, Down House, Downe, Greater London, Public Domain

- Darwin in South America (1832-35): © Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc, Fair Use

- An Artist’s Impression of Toxodon platensis and Smilodon populator: Prehistoric Park, © ITV plc, Fair Use

- An Artist’s Impression of Macrauchenia patachonica: © Jorge Blanco (artist), American Museum of Natural History, Fair Use

- An Artist’s Impression of Megatherium americanum: Robert Bruce Horsfall (artist), William B Scott, A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere, Page 220, The Macmillan Company, New York (1913), Public Domain

- An Artist’s Impression of Bos urus (Bos primigenius): Velizar Simeonovski (artist), Fair Use