Cumberland Cavern

Chapter V of Immanuel Velikovsky’s Earth in Upheaval bears the title Tidal Wave. The six sections of this chapter review the scientific evidence for catastrophic floods and megatsunamis in the Earth’s recent past. The third section, Cumberland Cavern, takes us to a fossil-filled cave on the outskirts of the city of Cumberland in Allegany County, Maryland.

Cumberland Bone Cave, as it is now known, was discovered in 1912 by engineers excavating a cut for the Western Maryland Railway in the side of Wills Mountain. A local naturalist, Raymond Armbruster, observed fossil bones among the limestone rocks that had been blasted loose from the cut. Armbruster notified paleontologists at the United States National Museum—the Smithsonian Institution—and in October of the same year James Gidley, the Smithsonian’s Assistant Curator of Fossil Mammals, was dispatched to make a preliminary examination of the find.

Although the limestone of Wills Mountain is of Devonian age, all the specimens collected from the cave and identified by Gidley are of Pleistocene age, suggesting that, roughly 200,000 years ago, the cave system was connected to the surface for a time by a sinkhole. Based on the probable topography, the sinkhole was approximately 100 feet deep, making it likely that anything that fell in would remain there. The fossils found are a mixture of animals that may have lived in the caves (such as bats, owls, and invertebrates), and some that may have fallen in, including terrestrial vertebrates (such as wolverines, bears, and peccaries), and numerous plants, all encased in sediments washed in over the years. Of the 41 genera listed from Cumberland Cave, eight are now extinct, and of 46 species, about 28 are extinct. (Anonymous)

The fossils were cemented together in a type of rock known as a cave breccia:

Cave breccias. These are formed in caverns by the cementing together of fragments falling from the roofs and sides of the caverns. (Haughton 59)

James Williams Gidley

Many of the sources Velikovsky cites in Earth in Upheaval were mavericks in their fields—creationists, catastrophists, amateurs, outsiders. This could not be said of James Williams Gidley, who was as mainstream as they come. James W Gidley was born in Springwater, Iowa, on the 7th of January 1866. He developed a passion for collecting fossils while exploring the nearby Black Hills during his childhood. He later studied science at Princeton University in New Jersey and at George Washington University in Washington, DC. In 1892, he was appointed Assistant in Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Gidley’s association with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, began in 1905 when he was appointed Preparator in the Section of Vertebrate Fossils. In 1907 he was promoted to Custodian of Fossil Mammals in the newly created Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, and in 1911 he became Assistant Curator of Fossil Mammals at the recently opened National Museum of Natural History, a post he retained for the remainder of his life:

Gidley’s career at the USNM was marked by several field explorations to collect fossil mammals. Included were trips to Maryland, Indiana, and Arizona. In the mid 1920s, he began a series of explorations around Melbourne and Vero Beach, Florida, in search of Pleistocene man. Gidley’s research interests were varied and he pursued studies of fossil mammals ranging from rodents to the horse. His bibliography listed 87 titles and included brief reports on the identity of specific specimens, as well as detailed studies of certain mammalian groups. (Smithsonian Institution Archives)

James W Gidley died on the 26th of September 1931 following a short illness. He was sixty-five years of age (Wetmore 32-33).

Cumberland Bone Cave

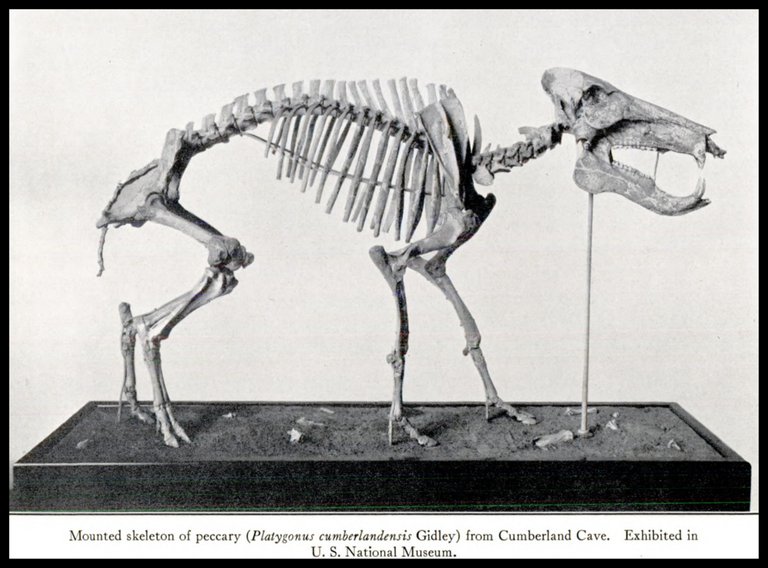

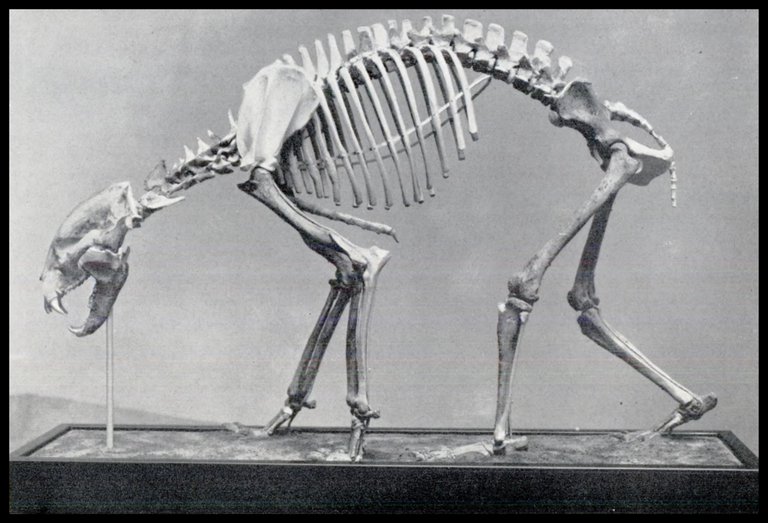

In October 1912, James Gidley made his first visit to the recently discovered Cumberland Bone Cave. Among the unearthed fossils, he identified about 24 species of mammals, most of them either extinct or now living only in localities very remote from the mountains of Western Maryland (Gidley 1913:49). The fossils were believed to date back to the Pleistocene Period.

In May 1913, Gidley paid a second visit to the bone cave. The number of mammalian species identified rose to forty, several of which were previously unknown. Gidley was struck by the chaotic assemblage of the fossils, which were brecciated rather than stratified:

This strange assemblage of fossil remains occurs hopelessly intermingled and comparatively thickly scattered through a more or less unevenly hardened mass of cave clays and breccias, which completely filled one or more small chambers of a limestone cave, the material together with the bones evidently having come to their final resting place through an ancient opening at the surface a hundred feet or more above their present location. (Gidley 1914:18)

Gidley made further visits to the cave in 1914 and 1915, adding a few more species to the list and several hundred more specimens to the Smithsonian’s collection of fossils.

Gidley was working on a comprehensive study of the Cumberland Bone Cave at the time of his death in 1931. The following year Charles Lewis Gazin, the Smithsonian’s newly-appointed Assistant Curator in the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, took up Gidley’s unfinished manuscript and completed the work. The Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Cumberland Cave, Maryland was published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1938.

Gidley believed that the bones were deposited in the cave in a single event, rather than accumulating there over aeons. Gazin, however, was not convinced of this:

Many of the species recognized are closely related to living forms, and it seems probable that their habits were not greatly different from those of living representatives.

The fauna from the cave includes a peculiar assemblage of animals. Many of the species are comparable to forms now living in the vicinity of the cave, but others are distinctly northern, or Boreal, in their affinities and some are related to species peculiar to the southern, or Lower Austral, region ...

The wolverine, Gulo, and lemmings of the group Mictomys are distinctly northern in range, and it seems highly improbable that they were contemporaneous in the same region with a crocodylid and a tapir ... A more probable explanation of the apparent association is that the fauna is not entirely contemporaneous and that the entombment extended over a period of time sufficient to allow important climatic changes to take place. The cave may have received material during a portion of a glacial and of an interglacial stage. Gidley (1920a) contended that the forms were contemporaneous in the same region, postulating greater relief, but the physiographic evidence does not seem to justify his reasoning.

Included among the forms that may well have been associated with wolverine and lemming mice in the colder fauna are the long-tailed shrew, fisher, mink, red squirrel, muskrat, porcupine, jumping mice, pika, hare, and elk; although in present distribution several of these extend well into the southern region. Suggesting warmer climatic conditions are bats and peccaries, in addition to crocodylid and tapir. Among those forms whose most closely related living representatives are now found much farther west are coyote, badger, pika, a pumalike cat, and a pocket gopher that resembles Thomomys more closely than it does Geomys. (Gidley & Gazin 6)

The range of habitats and climatic zones represented by the remains found in the cave is extraordinary:

The remains range in size from mastodon to bats and the diversity of types indicates that widely varying climate zones must have existed during the time of deposition. In the one cave have been found such types as the wolverine, grizzly bear, and Mustelidae which are native to the arctic. In the same cave have been found peccaries, which are the most numerous types represented, tapirs, and an antelope possibly related to the present-day eland, all of which are indigenous at present to tropical regions. Ground hogs, rabbits, coyote and hare remains are indicative of the prairielands, but on the other hand such water-loving animals as beaver and muskrat would suggest a more humid condition. (Nicholas 176)

Nicholas, a science teacher at LaSalle High School in Cumberland, favoured the gradual accumulation of these remains over a lengthy period of time. This seems to be the only gradualist hypothesis that accounts for the wide range of species. However, Gidley’s initial assessment that the remains were contemporaneous cannot be refuted. That the bones were deposited in the cave in a single event is indicated by the lack of stratification in the deposits. The remains were, as we have seen, hopelessly intermingled and thickly scattered through a more or less unevenly hardened mass of cave clays and breccias (Gidley 1914:18):

The bones for the most part are much broken, yet show no signs of being water worn. They are found scattered fairly uniformly throughout the entire mass of unstratified accumulations which consist entirely of cave clays and breccias, unevenly hardened and more or less cemented together by stalactitic materials. There is an almost entire absence of admixture of sand or gravel, or in fact anything that would suggest the possible aid of stream currents in sorting or placing the material during the process of accumulation. (Gidley & Gazin 3)

The fact that the bones show no evidence of having been water-worn might be adduced to refute Velikovsky’s claim that they were deposited in the cave by a megaflood. But Velikovsky believes that this particular detail actually confirms his hypothesis that the animals were swept up by a great flood when they were still alive and their carcasses were subsequently deposited in the cave. In other words, the bones were smashed when they were still inside their bodies. Only after the wrecked carcasses were deposited in the cave did the flesh decompose, leaving the bare bones to be encased in the hardening breccia:

The bones of the Cumberland cavern were “for the most part much broken, yet show no sign of being water worn.” This would signify that the bones were not carried for any length of time by a stream; however, it is quite possible that the animals were dashed against the rocks by an avalanche of water that carried them from far off, broke their bones inside their bodies—thus the bones are not water-worn—and there smashed together all kinds of animals; then gravel and rocks enclosed them. (Velikovsky 55)

Many of the species represented in the Cumberland assemblage are not native to this region. One, an eland or antelope, named Taurotragus americanus, belongs to a genus that is unknown in the New World. The two extant species of eland are only found in Africa. Gazin’s response to this discrepancy is to doubt Gidley’s identification:

An upper dentition (fig. 49) U.S.N.M. no. 7622, of a bovid type was described by Gidley (1913a) as representing a new eland, Taurotragus americanus. The living eland is African in distribution and belongs to a group of antilopine forms foreign to the New World. Hence, the recognition of Taurotragus in a North American cave deposit merits a critical reexamination of the fossil evidence. (Gidley & Gazin 86)

Concluding Remarks

It is impossible to square all the evidence from the Cumberland Bone Cave with a gradualist or uniformitarian explanation of the assemblage. On the contrary, the evidence implies a catastrophic event. The chaotic and unstratified nature of the cave breccia indicates that the bones were deposited in a single event. The variety of species represented indicates that the remains were carried to the cave from habitats thousands of kilometres apart. The lack of water erosion indicates that the animals were still alive when they were overtaken by the catastrophe:

Extinct animals are found there intermingled with extant forms. Death came to all of them at the same time. Any theory that attempts to explain the presence of animal bones from various climates in one and the same locality by a sequence of glacial and interglacial periods must stumble on the bones of the Cumberland cavern. (Velikovsky 56)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Anonymous, James W. Gidley: Expert in Cenozoic Mammals, Pennsylvania State University, University Park (2019)

- James Williams Gidley, A Newly Discovered Cave Deposit Near Cumberland, Maryland, in Explorations and Field-Work of the Smithsonian Institution in 1912, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 60, Number 30, Pages 49-50, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1913)

- James Williams Gidley, Further Exploration of the Cumberland Pleistocene Cave Deposit, in Explorations and Field-Work of the Smithsonian Institution in 1913, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 63, Number 8, Pages 16-18, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1914)

- James Williams Gidley, Fossil Collecting at the Cumberland Cave Deposit, in Explorations and Field-Work of the Smithsonian Institution in 1914, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Volume 65, Number 6, Pages 12-15, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1915)

- James Williams Gidley, Charles Lewis Gazin, The Pleistocene Vertebrate Fauna from Cumberland Cave, Maryland, United States National Museum Bulletin 171, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1938)

- S H Haughton, Breccias and Bones, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Volume 2, Number 7, Pages 59-67, South African Archaeological Society, Cape Town (1947)

- Brother G Nicholas, Recent Paleontological Discoveries in Cumberland, Maryland, Bone Cave, Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science, Volume 27, pp 174-178, Penn State University Press, University Park (1953)

- Alexander Wetmore, Report on the Progress and Condition of the United States National Museum for the Year Ended June 30, 1932, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (1932)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- Cumberland Bone Cave: © 2021 Great Allegheny Passage, Fair Use

- The National Museum of Natural History (Washington, DC): The Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain

- James Williams Gidley: Library of Congress, National Photo Company Collection, Public Domain

- Cumberland Bone Cave, Wills Mountain and Western Maryland Railway: Raymond Armbruster (photographer), Public Domain

- Composite Skeleton of a Peccary (Platygonus cumberlandensis Gidley): United States National Museum, Gidley & Gazin, Plate 10, Public Domain

- Composite Skeleton of a Black Bear (Euarctos vitabilis Gidley): United States National Museum, Gidley & Gazin, Plate 8, Public Domain

- Artist’s Impression of a Megaflood: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use