Medical microbiology, Enterobacteriaceae / Microbiologia medica, Enterobacteriaceae

Enterobacteriaceae

General Properties

Enterobacteria are a large family of bacteria that, physiologically, colonize our intestines; their pathogenicity is given by the acquisition of toxins from other bacteria.

The intestinal flora, composed of these bacteria, grows from the moment of birth and is very important because it produces fundamental substances, controls the immunity of the intestine (defined as the largest immune organ in the body) and allows the body to function properly, a feature that will then be reflected in the functions of many other organs.

Since the intestine is also in contact with the nervous system, these bacteria are able to cause pathologies even in the brain.

The great variety of families present is due to recombination phenomena through which these bacteria have acquired characters faded from one species to another from an antigenic, biochemical and genetic point of view; it is therefore complicated to identify a specific species because none of these has unique characteristics

Pathogenicity

As described above, most enterobacteria do not cause pathogenicity, however, there are 4 genera that are pathogenic. The contraction of an intestinal disease in most cases occurs via gold-fecal, ingesting a bacterium that alters the flora causing the pathology.

The two most frequent pathological conditions are diarrhoea (liquid discharge of faeces) and dysentery (liquid discharge of faeces containing mucus, live blood and pus); these are called pathologies exogenous.

There are also pathologies endogenic, due to the translocation of bacteria in the blood (due to intestinal blood loss, Crohn's disease, diverticulitis or colitis); a clear example of this type of pathology are endocarditis.

The bacterium can also reach the urinary tract (70% of urinary infections are due to these bacteria) or the respiratory tract.

There are species, among the pathogenic enterobacteria, that cause very characteristic pathologies such as Yersinia Pestis, responsible for the plague, and Salmonella Typhi, which causes typhoid, who will be the protagonist of the next article along with the shighelle.

Classification

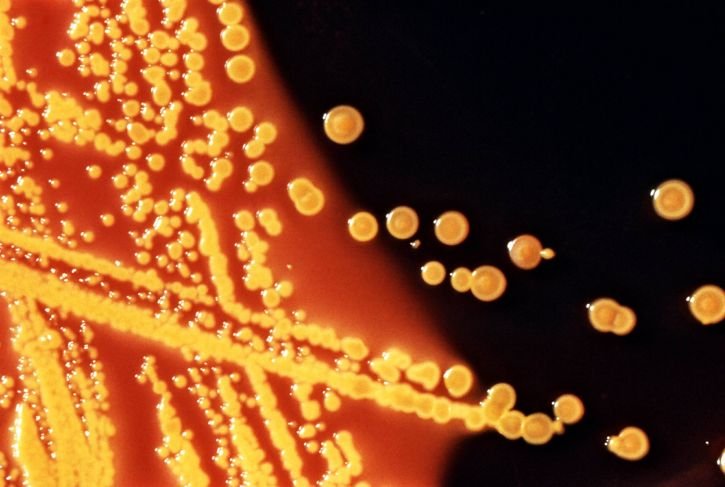

The classification is based on biochemical tests, carried out on soils with a single bacterium which, thanks to its metabolic activity, causes the soil to change colour according to the presence or absence of the bacterium.

A classification can also be made by means of an antigenic mode thanks to monoclonal antibodies that recognize certain antigens present in a bacterium. There are also the techniques of NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING (NGS), new techniques of DNA analysis that are very fast (100,000 sequences in little more than an hour) and give a more specific indication than any other technique.

General characteristics

Enterobacteria have rather similar characteristics to each other:

They are almost all gram-negative coccobacilli

They're asporigenous;

They can be mobile, immovable or fimbriated (thanks to the variability of the genetic code);

They may or may not present the capsule;

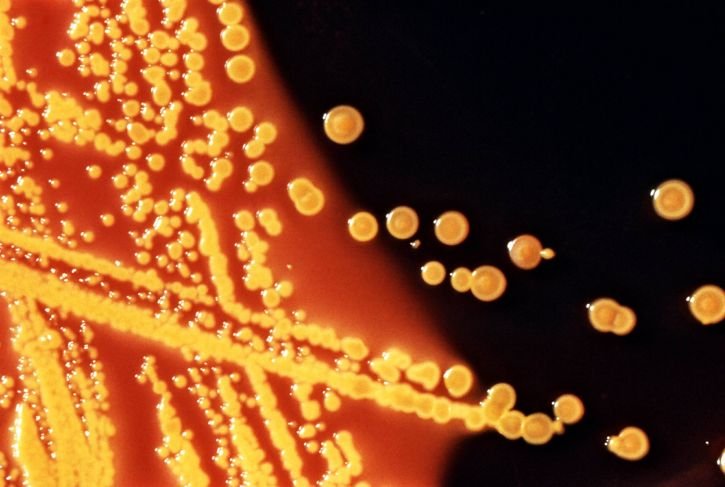

They grow easily on common culture media, but generally soils enriched with bile salts are used to isolate them from other bacteria;

They ferment different carbohydrates;

They are all optional aerobic-anaerobic, they carry out the mixed acid fermentation (from each molecule of glucose 4 ATP are obtained instead of the classic 2 thanks to the acetyl-coenzyme A which, containing sulphur, allows a higher yield);

They are all positive catalase but negative oxidase (this allows us to distinguish them from other bacteria such as Neisseria and Haemophilus);

They are ubiquitous: all organisms produce faeces, including animals, so the bacteria are present on plants, soil, water, human and animal intestines.

Clinical events

As far as exogenous pathologies are concerned, Salmonella and Shigella are the most important bacteria and cause infections in the intestine; as far as endogenous pathologies are concerned, intestinal bacteria can move to the nervous system, the respiratory tract and the urinary tract, causing infection in their respective districts (abscesses, pneumonia, meningitis considering strains with type B capsules, 50% of sepsis, infections following wounds, more than 70% of urinary tract infections).

The bacteria cause pathologies thanks to some toxins (not only endotoxins but also particular exotoxins), thanks to the capsular coating (through which they escape the immune system) and thanks to their strong resistance to antibiotics due to the extremely selective porine.

Characteristic antigens of enterobacteria

3 antigens are recognized: H antigen (outermost, flagellar or fimbrial antigen), K antigen (antibodies recognize the polysaccharide component on the capsule) and O antigen (the polysaccharide part of the endotoxin, not the lipid heart which is the toxic part.

To recognize the antigen O, being more internal, it is necessary to boil the bacterium (at 100 degrees) in order to eliminate the capsule (doing so, clearly, the antigens H and K are eliminated). In recent years a great many new species-specific antigens have been found; at the moment there are 200 somatic O antigens, 150 somatic K antigens and 50 somatic H antigens.

This classification is fundamental because it allows us to understand, at an epidemiological level, where a certain infection originated.

Diagnosis

For example, to analyse urine (in the case of urinary tract infection), soils containing bile salts are used to inhibit all the other bacteria present in the urine; these soils contain substances (such as lactose) that are metabolised by some bacteria and not by others, allowing the presence of certain bacterial species to be identified.

Urine is sown on McConkey's soil, a simpler environment for observing intestinal bacteria, consisting of bile salts, lactose and crystal violet; if the bacteria are fermenting, they will acidify the soil and from an initial beige colour the soil will become deep pink.

To identify an exogenous infection (e.g. salmonella) a more complex medium (Hektoen) containing lactose, bile, crystal violet, sodium thiosulphate and ferric ammonium citrate is used. The two salts are very important because salmonella produces a substance, hydrogen sulphate, which can precipitate them giving them a black color.

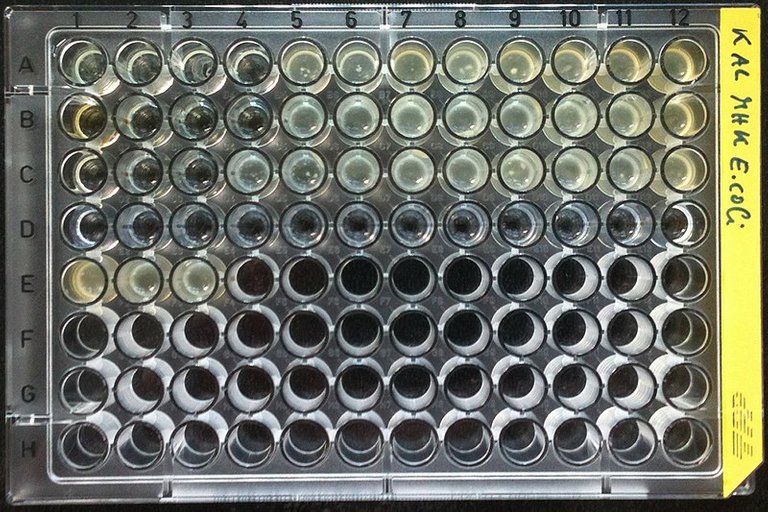

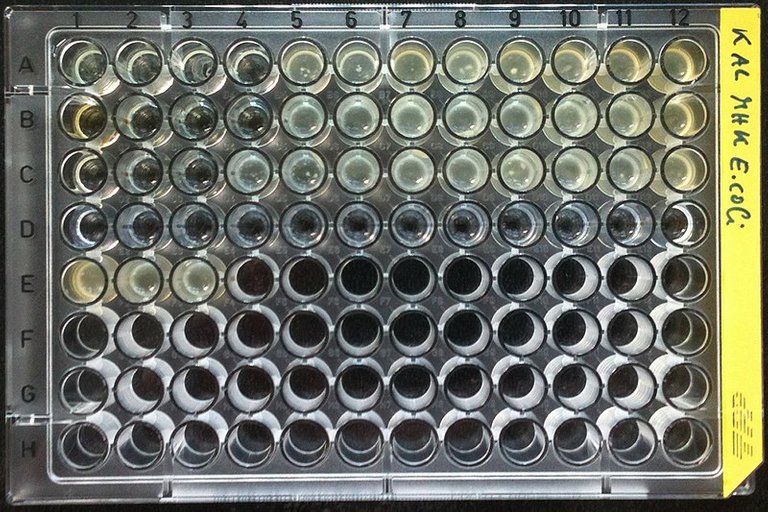

Biochemical tests are carried out inside cells containing different agars; all cells are inseminated thanks to the stick containing the same bacterium and then incubated, in this way it is possible to observe where the colour changes (the colour change is a sign of positivity); today this analysis is carried out on more than 400 soils with an attached antibiogram thanks to a machine.

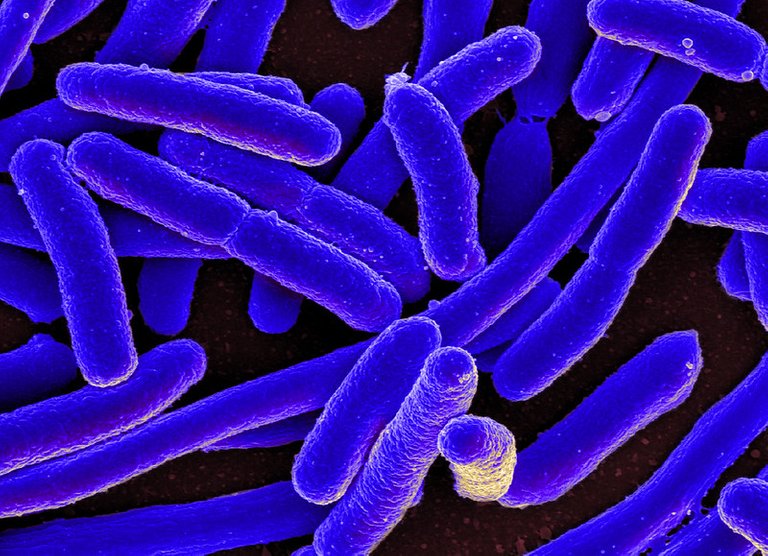

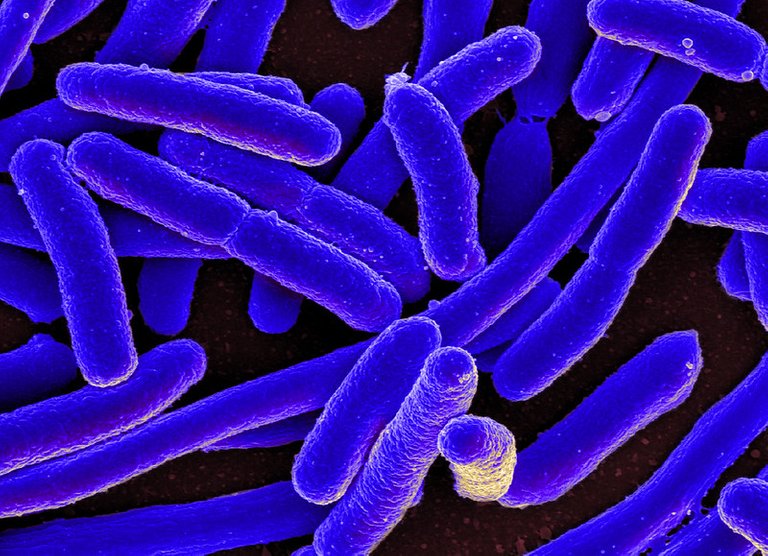

Escherichia Coli

It is the main component of the flora of the large intestine, is located in the last part of the colon as it tolerates very little bile salts, if you know many serotypes (171 antigens O, 80 antigens K, 56 antigens H), can be pathogenic in extraintestinal and intestinal sites (only some strains). Its pathogenicity factors are exotoxins, invasiveness (acquired by Shigellae) and adhesiveness (acquired by Salmonellae).

Pathogenic families

Four large families of pathogenic E. coli are considered, each with its own pathogenicity factors:

Etherotoxigens (ETEC): they have the ability to secrete enterotoxins, thermostable or thermolabile, transmissible thanks to plasmids (conjugation phenomenon) to all other bacteria. They cause strong diarrhoea because they induce the small intestine to produce more water than it should (they alter the balance between production of water in the small intestine and resorption through the villi in the colon); the disease is typically called traveler's diarrhoea (because one of the major causes are travel with poor sanitary conditions, cruises, developing countries ...), also causes vomiting, cramps, nausea and very mild fever;

Interoinvasive (EIEC): they have taken their characteristics from shigellae (through genetic recombinations), they pierce the intestinal mucosa thanks to some enzymes, in this way they grow in the submucosa generating pus; they cause dysentery (liquid stools containing mucus, pus and live blood) which, however, has limited severity as it is limited to the large intestine;

Interopathogens (EPEC): they contain some particular adhesives that allow them to adhere to the intestinal villi, forming a sort of "blanket" that prevents the proper performance of the function of the villus, thus causing diarrhea for lack of water reabsorption at the level of the large (unlike enterotoxinogens where the balance is disturbed at the level of the small);

EHEC: owes its toxin, called shiga-like toxin, to the shigella dysentery. This toxin causes the death of endothelial cells in adjacent capillaries, with associated bleeding of endothelials, without however causing damage to the mucosa; the blood vessels, bleeding, cause bleeding in the intestine and the blood is found in the faeces (normal, not liquid). If this toxin is produced in large quantities and reaches other areas, it can cause very serious damage (e.g. brain haemorrhages, renal glomerules, renal necrosis).

Mechanism of action of toxins

Enterotoxins: there are two types of them

1- Terminable: = is a toxin formed by two subunits (A and B), the subunit B binds to the cells of the small intestine thanks to some specific receptors, while the A is the toxic core, which is released within the cytoplasmic membrane of intestinal cells, then this subunit is divided into two subunits: A1 and A2. The first is the really toxic one because it activates the adenylate cyclase causing an energy deficit that leads the cell to block some highly energetic functions including the electrolytic pumps (responsible for maintaining the hydro-saline balance between inside and outside the cell), causing a loss of Cl-, which in turn leads to a call of water by the cells themselves, with the final effect of having a lot of water in the intestine;

2- Thermostable = Unlike thermostable, there is no entry of toxin into the cell, however, it interacts with a receptor that translates directly into the cell a signal for activation of guanylate cyclase.

Shiga-like toxin: the toxin spreads locally (through its absorption into the intestine), binds to endothelial cells that stop producing proteins (it stops being produced an elongation factor in the ribosome); this causes cell death with consequent haemorrhagic colitis. If this happens in the kidney, it causes hemolytic uremic syndrome (destruction of renal glomerules by lysis of endothelial cells); if it happens in the CNS, it causes ischemic phenomena.

Treatment

Antibiotics, mainly quinolones but also broad-spectrum β-lactanes or tetracyclines. If possible, it is preferable to carry out a faecal examination with an antibiogram to evaluate the best antibiotic to be administered.

Now a little challenge to the readers

Imagine being in a luxury hotel near Rio de janeiro, you are aware of the problems that can arise from eating untreated food and you have been careful to order only cooked food and drink only bottled water in order to avoid possible unpleasant infections.

In the evening in the hotel there is a small evening at the Piano bar, where you can listen to live music and drink an aperitif with friends.

You scrupulous as always order a Negroni, composed of the classic recipe (1/3 of gin, 1/3 of bitter Campari and 1/3 of red vermouth), each bottle of alcohol is opened in front of you and the coktail is placed in the glass with ice by the Barman.

The next day, you feel bad, and you discover that you have been infected by E. coli.

How did it happen? What was the vehicle of the infection given your great care?

Try to think about it and give an answer

the solution to this little challenge can be found in the comments :)

Enterobacteriaceae

Proprietà generali

Gli enterobatteri sono una grande famiglia di batteri che, fisiologicamente, colonizza il nostro intestino; la loro patogenicità è data dall’acquisizione di tossine da altri batteri.

La flora intestinale, composta da questi batteri, cresce dal momento della nascita ed è molto importante in quanto produce sostanze fondamentali, controlla l’immunità dell’intestino (definito come il più grande organo immune del corpo) e permette a quest’ultimo di funzionare correttamente, caratteristica che poi andrà a riflettersi sulle funzioni di tantissimi altri organi.

Essendo l’intestino in contatto anche con il sistema nervoso, questi batteri sono in grado di causare patologie anche a livello cerebrale.

La grande varietà di famiglie presenti è dovuta a fenomeni di ricombinazione tramite i quali questi batteri hanno acquisito caratteri sfumati da una specie all’altra da un punto di vista antigenico, biochimico e genetico; risulta perciò complicato identificarne una precisa specie poiché nessuna di queste ha caratteristiche univoche.

Patogenicità

Come precedentemente descritto, la maggior parte degli enterobatteri non causa patogenicità, esistono tuttavia 4 generi che risultano invece patogeni. La contrazione di una malattia intestinale nella maggior parte dei casi avviene per via oro-fecale, ingerendo un batterio che altera la flora causando la patologia.

Le due condizioni patologiche più frequenti sono la diarrea (scarica liquida di feci) e la dissenteria (scarica di feci liquide contenenti muco, sangue vivo e pus); queste sono chiamate patologie esogene.

Esistono anche patologie endogene, dovute alla traslocazione dei batteri nel sangue (dovuta a perdite di sangue intestinali, morbo di Crohn, diverticoliti o coliti); un esempio lampante di questo tipo di patologia sono le endocarditi.

Il batterio può anche arrivare alle vie urinarie (il 70% delle infezioni urinarie sono dovute a questi batteri) o nelle vie respiratorie.

Esistono specie, tra gli enterobatteri patogeni, che causano patologie molto caratteristiche come ad esempio Yersinia Pestis, responsabile della peste, e Salmonella Typhi, che causa il tifo, e che sarà la protagonista del prossimo articolo insieme alle shighelle.

Classificazione

La classificazione si basa su prove biochimiche, effettuate su terreni con un singolo batterio che, grazie alla sua attività metabolica, fa in modo che il terreno cambi colore in base alla presenza o meno del batterio.

Si può effettuare una classificazione anche tramite una modalità antigenica grazie ad anticorpi monoclonali che riconoscono determinati antigeni presenti in un batterio. Ci sono inoltre le tecniche di NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING (NGS), nuove tecniche di analisi del DNA che risultano molto rapide (100.000 sequenze in poco più di un’ora) e danno un’indicazione più specifica di qualsiasi altra tecnica.

Caratteristiche generali

Gli enterobatteri presentano caratteristiche piuttosto simili tra loro:

• Sono quasi tutti coccobacilli gram negativi

• Sono asporigeni;

• Possono essere mobili, immobili o fimbriati (grazie alla variabilità del codice genetico);

• Possono presentare o meno la capsula;

• Crescono facilmente su comuni terreni di coltura, ma generalmente si usano terreni arricchiti di sali biliari per isolarli dagli altri batteri;

• Fermentano diversi carboidrati;

• Sono tutti aerobi-anaerobi facoltativi, effettuano la fermentazione acida mista (da ogni molecola di glucosio si ottengono 4 ATP anziché i classici 2 grazie all’acetil-coenzima A che, contenendo zolfo, permette una resa maggiore);

• Sono tutti catalasi positivi ma ossidasi negativi (ciò ci permette di distinguerli da altri batteri quali Neisseria e Haemophilus);

• Sono ubiquitari: tutti gli organismi producono feci, animali compresi, i batteri risultano perciò presenti su piante, terreno, acqua, intestino umano e di animali.

Manifestazioni in ambito clinico

Parlando di patologie esogene la Salmonella e la Shigella sono i batteri più importanti e causano infezioni a carico dell’intestino ; per quanto riguarda le patologie endogene i batteri intestinali possono traslocare a livello del sistema nervoso, delle vie respiratorie e delle vie urinarie causando infezione nei rispettivi distretti (ascessi, polmoniti, meningiti considerando ceppi con capsula di tipo B, il 50% delle sepsi, infezioni successive a ferite, oltre il 70% delle infezioni del tratto urinario).

I batteri causano patologie grazie ad alcune tossine (non solo endotossine ma anche particolari esotossine), grazie al rivestimento capsulare (tramite il quale sfuggono al sistema immunitario) e grazie alla loro forte resistenza agli antibiotici dovuta alle porine estremamente selettive.

Antigeni caratteristici degli enterobatteri

Si riconoscono 3 antigeni: antigene H (più esterno, antigene flagellare o di fimbrie), antigene K (gli anticorpi riconoscono la componente polisaccaridica sulla capsula) e antigene O (la parte polisaccaridica dell’endotossina, non il cuore lipidico che è invece la parte tossica.

Per riconoscere l’antigene O, essendo più interno, è necessario far bollire il batterio (a 100 gradi) in modo da eliminare la capsula (così facendo, chiaramente, vengono eliminati gli antigeni H e K). Negli ultimi anni sono stati trovati moltissimi nuovi antigeni specie-specifici; al momento esistono 200 antigeni somatici O, 150 antigeni somatici K e 50 antigeni somatici H.

Questa classificazione è fondamentale perché permette di capire, a livello epidemiologico, da dove è partita una certa infezione.

Diagnosi

Per analizzare, ad esempio, le urine (in caso di infezione delle vie urinarie) si utilizzano terreni contenenti sali biliari che vanno ad inibire tutti gli altri batteri presenti nelle urine; questi terreni contengono sostanze (come il lattosio) che vengono metabolizzate da alcuni batteri e non da altri, permettendo di identificare la presenza di determinate specie batteriche.

L’urina si semina sul terreno di McConkey, ambiente più semplice per osservare batteri intestinali, costituito da sali biliari, lattosio e cristalvioletto ; se i batteri sono fermentanti acidificheranno il terreno e da un iniziale colore beige il terreno diventerà rosa intenso.

Per identificare un’infezione esogena (es. salmonella) si utilizza un terreno più complesso (Hektoen) contenente lattosio, bile, cristalvioletto, tiosolfato di sodio e citrato di ammonio ferrico. I due sali sono molto importanti perché la salmonella produce una sostanza, l’idrogenosolfato, in grado di farli precipitare dando un colore nero.

Le prove biochimiche vengono effettuate all’interno di cellette contenenti agar differenti; si inseminano tutte le cellette grazie al bastoncino contenente lo stesso batterio e poi lo si incuba, in questo modo si può osservare dove il colore cambia (il cambiamento di colore è indice di positività); oggi questa analisi viene fatta su oltre 400 terreni con annesso antibiogramma grazie ad una macchina.

Escherichia Coli

È il principale componente della flora dell’intestino crasso, si trova nell’ultima parte del colon in quanto tollera pochissimo i sali biliari, se ne conoscono numerosi sierotipi (171 antigeni O, 80 antigeni K, 56 antigeni H), può essere patogeno in sedi extraintestinali ed intestinali (solo alcuni ceppi). I suoi fattori di patogenicità sono le esotossine, l’invasività (acquisita dalle Shigelle) e l’adesività (acquisita dalle Salmonelle).

Famiglie patogene

Si considerano 4 grandi famiglie di E. Coli patogene, ognuna con propri fattori di patogenicità :

• Enterotossigeni (ETEC): hanno la capacità di secernere enterotossine, termostabili o termolabili, trasmissibili grazie ai plasmidi (fenomeno della coniugazione) a tutti gli altri batteri. Causano forte diarrea in quanto inducono l’intestino tenue a produrre più acqua del dovuto (vanno ad alterare l’equilibrio tra produzione di acqua nel tenue e riassorbimento tramite i villi nel colon ); la patologia è tipicamente chiamata diarrea del viaggatore (perché una delle cause maggiori sono viaggi con condizioni igienico-sanitarie non perfette, crociere, paesi in via di sviluppo…), causa anche vomito, crampi, nausea e febbre molto lieve;

• Enteroinvasivi (EIEC): hanno preso le loro caratteristiche dalle shigelle (tramite ricombinazioni genetiche), bucano la mucosa intestinale grazie ad alcuni enzimi, in questo modo vanno a crescere nella sottomucosa generando pus; causano dissenteria (feci liquide contenenti muco, pus e sangue vivo) che ha però gravità limitata in quanto è circoscritta all’intestino crasso;

• Enteropatogeni (EPEC): contengono alcune adesine particolari che gli permettono l’adesione ai villi intestinali, andando a formare una sorta di “coperta” che impedisce il corretto svolgimento della funzione del villo, causando perciò diarrea per mancato riassorbimento di acqua a livello del crasso (a differenza degli enterotossinogeni dove l’equilibrio è perturbato a livello del tenue);

• Enteroemorragici (EHEC): deve la sua tossina, chiamata tossina shiga-like, alla shigella dysenterie. Questa tossina causa la morte di cellule endoteliali dei capillari adiacenti, con annesso sanguinamento degli endoteli, senza tuttavia causare danni alla mucosa; i vasi, sanguinando, causano emorragia a livello intestinale e il sangue è riscontrabile a livello delle feci (normali, non liquide). Se questa tossina viene prodotta in grande quantità e raggiunge altre zone può causare danni gravissimi (es. nel cervello emorragie cerebrali, nei glomeruli renali necrosi renale).

Meccanismo di azione delle tossine

Enterotossine: ne esistono di due tipi

1- Termolabile: = è una tossina formata da due subunità (A e B), la subunità B si lega alle cellule dell’intestino tenue grazie ad alcuni recettori specifici, mentre la A è il core tossico, che viene liberato all’interno della membrana citoplasmatica delle cellule intestinali; successivamente questa subunità si suddivide in due sotto-subunità: A1 e A2. La prima è quella realmente tossica poiché attiva l’adenilato ciclasi causando un deficit energetico che porta la cellula a bloccare alcune funzioni altamente energetiche tra le quali le pompe elettrolitiche (responsabili del mantenimento dell’equilibrio idrosalino tra interno ed esterno della cellula), causando una perdita di Cl-, che a sua volta porta ad un richiamo dell’acqua da parte delle cellule stesse, con effetto finale di avere molta acqua nell’intestino;

2- Termostabile = A differenza della termolabile non vi è l’ingresso della tossina nella cellula, tuttavia essa interagisce con un recettore che trasduce direttamente nella cellula un segnale per l’attivazione della guanilato ciclasi .

Tossina shiga-like: la tossina diffonde a livello locale (tramite assorbimento della stessa nell’intestino), si lega a cellule endoteliali che smettono di produrre proteine (smette di essere prodotto un fattore di allungamento nel ribosoma); ciò causa morte cellulare con conseguente colite emorragica. Se questo accade nel rene causa sindrome uremico emolitica (distruzione dei glomeruli renali per lisi degli endoteli); se invece avviene nel SNC causa fenomeni ischemici.

Trattamento

Antibiotici, principalmente chinolonici ma anche β-lattanici ad ampio spettro o tetracicline. Se possibile è preferibile effettuare un esame delle feci con antibiogramma per valutare il miglior antibiotico da somministrare.

Ora una piccola sfida ai lettori

Immaginate di essere in un lussuoso albergo dalle parti di Rio de janeiro, siete a conoscenza delle problematiche che possono scaturire dal mangiare cibo non trattato e siete stati attenti ad ordinare solo cibo cotto e a bere solo acqua in bottiglia in modo tale da evitare possibili spiacevoli infezioni.

La sera in Albergo c'è una piccola serata al Piano bar, dove si ascolta musica dal vivo e si beve un aperitivo in compagnia.

Voi scrupolosi come sempre ordinate un Negroni, composto dalla ricetta classica ( 1/3 di gin, 1/3 di bitter Campari e 1/3 di vermut rosso), ogni bottiglia di alcolico vi viene aperta di fronte e il coktail viene posizionato nel bicchiere con il ghiaccio dal Barman.

Il giorno successivo, vi sentite male, e scoprite che siete stati infettati da E. Coli.

Come è successo? Quale è stato il veicolo dell'infezione vista la vostra grande scrupolosità?

Provate a pensarci e a dare una risposta

la soluzione a questa piccola sfida la trovate nei commenti :)

Fonti/Sources

Immagini/Pictures

The answer to the question is that despite having been scrupulous, the vehicle of contamination was the ice in the cocktail, which made possible the contamination, in fact, if the water system has problems an infection with Escherichia Coli is absolutely plausible and common, causing the diarrhea of the traveler. :)

La risposta al quesito è che malgrado l'essere stati scrupolosi, il veicolo di contaminazione è stato il ghiaccio nel cocktail, che ha reso possibile la contaminazione, infatti se l'impianto idrico presenta delle problematiche un infezione da Escherichia Coli è assolutamente plausibile e comune, causando la diarrea del viaggiatore.

This post was selected, voted and shared by the discovery-it curation team in collaboration with the C-Squared Curation Collective. You can use the #Discovery-it tag to make your posts easy to find in the eyes of the curator. We also encourage you to vote @c-squared as a witness to support this project.

Congratulations @riccc96! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Secondo me è colpa del bicchiere dato che magari prima era stata versata dell'acqua non controllata! E in seguito ovviamente non lavato correttamente!

Grandissimo! è più che plausibile, hai trovato una seconda soluzione, la prima era il ghiaccio ma anche tutto il processo che ruota attorno al bicchiere può essere veicolo di infezione!

una terza soluzione potebbero anche essere le mani del Barman non pulite alla perfezione, ma è la meno plausibile!

La prossima volta che andrò in un bar non prendo nulla, così evito tutto!

Hello,

Your post has been manually curated by a @stem.steem curator.

We are dedicated to supporting great content, like yours on the STEMGeeks tribe.

Please join us on discord.

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail. It is elligible for support from @curie and @minnowbooster.

If you appreciate the work we are doing, then consider supporting our witness @stem.witness. Additional witness support to the curie witness would be appreciated as well.

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!

Please consider using the steemstem.io app and/or including @steemstem in the list of beneficiaries of this post. This could yield a stronger support from SteemSTEM.

I am not a Biology or Medical expert but I always appreciate good content when I see it. Thank you.