Welcome to the fascinating world of the rectum - the final frontier of the digestive system!

Source

Nestled within the depths of the pelvic cavity, the rectum holds the secrets of waste elimination and plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of our body's internal environment.

Often overlooked, the rectum serves as the grand finale of the large intestine's journey. Like a diligent stagehand, it awaits the arrival of the digested remnants from the sigmoid colon, where nutrients have been extracted and absorbed along the way. With precision and finesse, the rectum assumes its vital responsibility as a temporary storage reservoir for fecal matter, patiently biding its time until the grand performance of defecation begins.

But the rectum is far more than a mere storage facility. Its intricate anatomy and muscular structure orchestrate a symphony of movements, seamlessly propelling the fecal material toward its ultimate destination - the anal canal. Through a delicate dance of muscular contractions, the rectum collaborates with the surrounding structures to ensure the smooth passage of waste, contributing to the intricate choreography of our digestive system.

Exploring the anatomy of the rectum unveils a world of wonder and complexity. From the curvatures that navigate the contours of the pelvis to the intricate network of blood vessels and nerve fibers that sustain its function, the rectum is a marvel of anatomical ingenuity. Understanding its structure and function empowers medical professionals to diagnose and treat a multitude of rectal conditions while offering individuals a newfound appreciation for the sophistication of their bodies.

So join us on this captivating journey into the depths of the rectum, where knowledge awaits. Delve into its chambers, discover the secrets of its blood supply, marvel at its nerve connections, and unravel the mysteries that lie within.

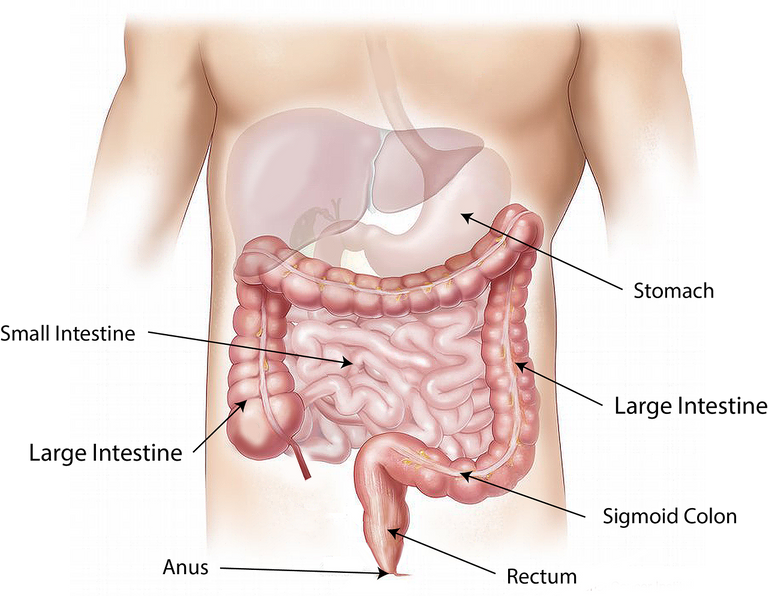

Location and General Overview

The rectum is located within the pelvic cavity, specifically in the posterior portion of the pelvis. It serves as the terminal part of the large intestine, extending from the sigmoid colon to the anal canal.

To understand its precise location, we can visualize the pelvic cavity as a basin-shaped structure. The rectum lies in the most inferior part of this basin, anterior to the sacrum and coccyx (the bones at the base of the spine) and posterior to the urinary bladder (in males) or the uterus and vagina (in females). It sits between these structures, forming an important part of the pelvic floor.

The rectum follows a curved path within the pelvis, known as the rectal curvature. It initially extends anteriorly from the sigmoid colon and then curves posteriorly as it descends. This curvature allows the rectum to accommodate and store fecal matter before the act of defecation.

The precise positioning of the rectum within the pelvis can vary slightly among individuals due to anatomical variations. However, its general location remains consistent as the final segment of the large intestine, bridging the gap between the sigmoid colon and the anal canal.

The approximate length of the rectum in adults can vary depending on factors such as age, body size, and individual anatomical variations. On average, the length of the rectum in adults ranges from about 12 to 15 centimeters (4.7 to 5.9 inches).

The rectum begins at the level of the sacral promontory, which is a bony prominence at the anterior aspect of the sacrum. It extends downward and posteriorly, curving within the pelvic cavity. At its lower end, the rectum transitions into the anal canal.

It's important to note that the length of the rectum can vary among individuals. Factors such as the degree of rectal distension, the presence of rectal folds, and the individual's body composition can influence the measured length. Additionally, certain medical conditions or surgical procedures may impact the length of the rectum.

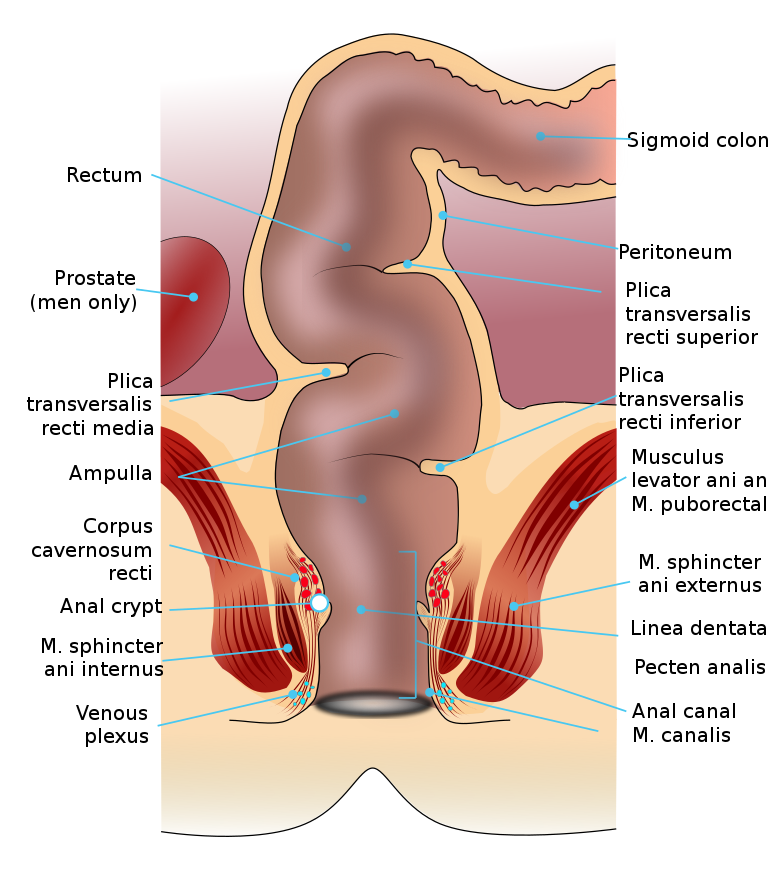

The three main sections of the rectum and the curvature

The rectum can be divided into three main sections: the upper rectum, the middle rectum, and the lower rectum. Each section has its own distinct anatomical and functional characteristics.

Upper Rectum: The upper rectum is the first segment of the rectum that follows the sigmoid colon. It begins at the level of the sacral promontory, which is a bony prominence at the anterior aspect of the sacrum. This portion of the rectum is relatively fixed in its position due to ligamentous attachments, including the sigmoid mesocolon. The upper rectum receives fecal material from the sigmoid colon and serves as a temporary storage site.

Middle Rectum: The middle rectum extends from the upper rectum to the level of the pelvic floor muscles, known as the levator ani muscles. This section of the rectum continues the posterior and slightly downward course within the pelvic cavity. The middle rectum is relatively mobile compared to the upper rectum and can exhibit some variation in position depending on factors such as rectal distension and pelvic floor tone.

Lower Rectum: The lower rectum is the final segment of the rectum, located within the pelvic cavity and just above the anal canal. It begins at the level of the pelvic floor muscles and terminates at the pectinate line. The lower rectum is narrower than the upper and middle rectum and has a thicker muscular layer. This section of the rectum plays a crucial role in maintaining continence and facilitating the controlled passage of fecal material into the anal canal during defecation.

Understanding the three main sections of the rectum helps healthcare professionals in assessing and diagnosing rectal conditions, performing rectal examinations, and planning appropriate treatment strategies. It also provides individuals with a better understanding of the anatomical organization of the rectum and its role in the digestive process.

The Curvature

The curvature of the rectum within the pelvis refers to the natural bend or flexure that occurs along the course of the rectum as it descends from the sigmoid colon towards the anal canal. This curvature is known as the rectal curvature or rectal flexure.

The rectal curvature can be described as an anterior or forward-facing curve that transitions into a posterior or backward-facing curve. This curvature allows the rectum to adapt and accommodate the pelvic anatomy, facilitating its function as a storage reservoir for fecal material.

The anterior curve of the rectal curvature occurs at the upper part of the rectum, where it meets the sigmoid colon. This initial anterior flexure is formed by the sigmoid colon angling forward as it enters the pelvis. The sigmoid colon, which is located in the left lower abdomen, bends anteriorly at the level of the sacral promontory and transitions into the upper rectum.

As the rectum descends further within the pelvis, it transitions into a posterior curve. This posterior flexure occurs due to the interaction between the rectum and the pelvic structures, including the sacrum and coccyx, which lie posteriorly. The rectum follows the concavity of the sacrum and coccyx, curving backward and downward towards the anal canal.

The rectal curvature is important in maintaining rectal continence and facilitating the expulsion of fecal material during defecation. The curved shape helps to prevent involuntary passage while allowing for controlled elimination when appropriate.

Structure of the Rectum

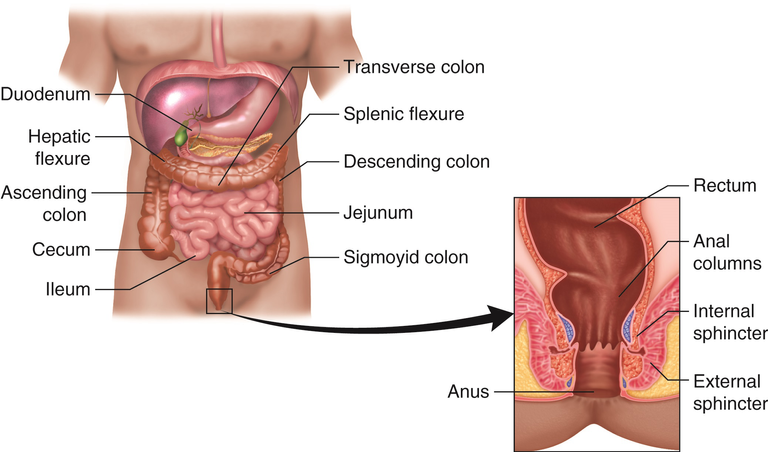

The Rectum Wall

The rectal wall consists of several layers, each with its distinct structure and function. These layers, from innermost to outermost, include the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and adventitia/serosa (depending on the specific location within the rectum). Let's explore each layer in more detail:

Mucosa: The mucosa is the innermost layer of the rectal wall. It is composed of specialized epithelial cells that line the inner surface of the rectum. The mucosa contains numerous small glands, known as rectal glands, which secrete mucus to lubricate the passage of stool. The mucosa also contains blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves that play a role in various rectal functions.

Submucosa: The submucosa lies beneath the mucosa and is made up of connective tissue. It contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and larger nerves that supply the rectal wall. The submucosa provides support and nourishment to the overlying mucosa.

Muscularis Propria: The muscularis propria is a thick layer of smooth muscle that surrounds the submucosa. It consists of two layers of smooth muscle fibers: an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer. The circular muscle layer helps in the constriction of the rectal lumen, while the longitudinal muscle layer aids in the shortening and lengthening of the rectum during peristaltic movements.

Adventitia/Serosa: The outermost layer of the rectal wall can vary depending on its location within the rectum. In the upper and middle rectum, the outer layer is composed of connective tissue called the adventitia. It provides support and attaches the rectum to surrounding structures. In the lower rectum, the outer layer transitions into the serosa, which is a serous membrane that covers and protects the rectum.

It's important to note that the rectal wall is richly supplied with blood vessels and nerve fibers, including sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. These innervations play crucial roles in the control of rectal muscle contractions, sensation, and the coordination of defecation.

Smooth muscle arrangement

The smooth muscle fibers in the rectal wall are arranged in two main layers: the inner circular layer and the outer longitudinal layer. These layers work together to facilitate the movement and function of the rectum.

Inner Circular Layer: The inner circular layer consists of smooth muscle fibers that encircle the circumference of the rectum. These muscle fibers form a ring-like structure. When they contract, they cause a narrowing or constriction of the rectal lumen. This constriction helps to create resistance and maintain control over the movement of fecal material within the rectum. The circular muscle layer also contributes to the formation of internal sphincters, which aid in maintaining continence.

Outer Longitudinal Layer: The outer longitudinal layer consists of smooth muscle fibers that run parallel to the long axis of the rectum. These muscle fibers extend from the upper rectum to the lower rectum. When they contract, they shorten the length of the rectum and help to propel fecal material toward the anal canal. The longitudinal muscle layer aids in the peristaltic movements of the rectum, which involve rhythmic contractions and relaxations of the muscles to facilitate the movement of stool.

The arrangement of smooth muscle fibers in these two layers allows for coordinated movements and control within the rectum. The circular layer provides the ability to constrict and hold fecal material, while the longitudinal layer facilitates propulsion and the expulsion of stool during defecation. The combined actions of these layers, along with the help of other muscles and structures in the pelvic floor, contribute to the overall functioning of the rectum.

The role of the rectal muscles in the process of defecation

The rectal muscles play a vital role in the process of defecation, which is the elimination of waste material from the body. Here's a brief highlight of their role:

Internal Anal Sphincter: The internal anal sphincter is an involuntary smooth muscle ring located at the junction between the rectum and the anal canal. It remains contracted to maintain continence and prevent the involuntary passage of stool. During the process of defecation, the internal anal sphincter relaxes in response to the stretch of the rectum, allowing the passage of stool into the anal canal.

Rectal Wall Muscles: The circular and longitudinal smooth muscles within the rectal wall play a key role in the propulsion and expulsion of fecal material. As stool enters the rectum, the circular muscle layer contracts, causing the rectal walls to constrict and create resistance. This contraction helps to maintain the fecal material within the rectum until an appropriate time for defecation. Simultaneously, the longitudinal muscle layer contracts and shortens, assisting in the movement of stool toward the anal canal.

External Anal Sphincter: The external anal sphincter is a voluntary skeletal muscle that surrounds the internal anal sphincter. It is under conscious control and helps to maintain continence by keeping the anal canal closed. During defecation, the external anal sphincter relaxes voluntarily, allowing the passage of stool out of the body.

The coordinated relaxation and contraction of the rectal muscles, along with the relaxation of the internal and external anal sphincters, are essential for the controlled and voluntary process of defecation. The rectal muscles work together to store and propel fecal material through the rectum and anal canal, while the anal sphincters provide control over the release of stool.

Blood Supply and Venous Drainage

Arterial Supply

The rectum receives its arterial blood supply from several sources, including the superior rectal artery, middle rectal artery, and inferior rectal artery. Let's discuss each of these arteries and their contribution to the rectal blood supply:

Superior Rectal Artery: The superior rectal artery, also known as the superior hemorrhoidal artery, is a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. It supplies the upper part of the rectum. The superior rectal artery typically enters the rectum through the posterior wall and travels downward along the length of the rectum, providing oxygenated blood to its mucosa, submucosa, and muscular layers. This artery anastomoses (connects) the middle rectal artery, ensuring collateral circulation in case of any vascular compromise.

Middle Rectal Artery: The middle rectal artery usually arises from the internal iliac artery. It branches off into multiple vessels that supply the middle part of the rectum. These arteries penetrate the muscular layers of the rectal wall, providing blood to the submucosa, muscularis propria, and surrounding structures.

Inferior Rectal Artery: The inferior rectal artery is a branch of the internal pudendal artery, which itself arises from the internal iliac artery. It supplies the lower part of the rectum, including the anal canal and the external anal sphincter. The inferior rectal artery gives rise to numerous branches that penetrate the rectal wall and provide blood to the distal rectum and anal canal. These branches also contribute to the vascular supply of the perianal region.

The arterial blood supply to the rectum is crucial for maintaining the viability and normal functioning of its various layers. Adequate blood flow ensures proper oxygenation and nutrient supply to the rectal tissues, allowing for their normal physiological processes.

Venous Drainage

The venous drainage of the rectum involves multiple routes, including the superior rectal vein, middle rectal veins, and inferior rectal veins. Here's an explanation of the venous drainage pathways:

Superior Rectal Vein: The superior rectal vein, also known as the superior hemorrhoidal vein, is the primary venous drainage vessel for the upper part of the rectum. It typically accompanies the corresponding superior rectal artery and runs parallel to it. The superior rectal vein drains blood from the rectal venous plexus, which is a network of veins located in the submucosa and muscular layers of the rectum. It then follows the path of the superior rectal artery, ultimately draining into the portal venous system through the inferior mesenteric vein. This venous drainage pathway is significant because it connects the rectal circulation to the liver through the portal vein.

Middle Rectal Veins: The middle rectal veins arise from the venous plexus within the middle part of the rectum. They typically accompany the corresponding middle rectal arteries. These veins primarily drain into the internal iliac vein, which is a major vein located in the pelvic region. The internal iliac vein eventually joins the common iliac vein, contributing to systemic venous circulation.

Inferior Rectal Veins: The inferior rectal veins drain the lower part of the rectum, including the anal canal and the perianal region. They are interconnected with the middle rectal veins and form an anastomotic network known as the rectal venous plexus. The blood from the inferior rectal veins typically drains into the internal iliac veins, similar to the middle rectal veins.

The venous drainage pathways of the rectum are significant because they can contribute to the development of hemorrhoids (enlarged and swollen veins in the rectum and anus) and other conditions related to venous congestion. The anastomotic connections between the portal and systemic venous systems in the rectal region also have clinical implications in certain disease scenarios, such as portal hypertension.

Nerve Supply

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a crucial role in regulating various aspects of rectal function. It consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions, which work together to maintain the balance and control of rectal activities.

The rectum receives both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation, which play essential roles in regulating its function.

- Sympathetic Innervation: The sympathetic innervation of the rectum arises from the thoracic and lumbar levels of the spinal cord. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers originate in the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord and travel through the sympathetic chain ganglia. From there, postganglionic sympathetic fibers extend to the rectum. These sympathetic fibers primarily originate from the superior mesenteric ganglion and travel along the superior rectal artery to reach the rectum.

The sympathetic innervation to the rectum functions to inhibit smooth muscle activity and decrease peristalsis, promoting relaxation and storage of fecal material. Sympathetic stimulation also causes vasoconstriction, reducing blood flow to the rectum.

- Parasympathetic Innervation: The parasympathetic innervation of the rectum arises from the sacral levels of the spinal cord. Preganglionic parasympathetic fibers originate in the intermediolateral cell column of the sacral spinal cord segments S2-S4. These fibers form the pelvic splanchnic nerves (pelvic nerves) and travel to the inferior hypogastric plexus.

From the inferior hypogastric plexus, postganglionic parasympathetic fibers continue to the rectum. They innervate the rectal wall, including the smooth muscles and glands. Parasympathetic stimulation promotes peristalsis, increases rectal contractions, and enhances the relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. It also promotes the secretion of mucus and enhances blood flow to the rectal area.

The balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation is crucial for the regulation of rectal function, including the storage and elimination of fecal material. The sympathetic system helps maintain fecal material within the rectum, while the parasympathetic system promotes defecation by facilitating the movement of stool through the rectum and relaxation of the internal anal sphincter.

Disruptions in the autonomic nervous system can lead to various rectal disorders, such as constipation, fecal incontinence, and neurogenic bowel dysfunction.

Lymphatic Drainage

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum involves a complex network of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessels serve to transport lymph, a clear fluid containing immune cells and waste products, away from tissues and toward lymph nodes. Here's an explanation of the lymphatic drainage of the rectum and the involvement of the pararectal lymph nodes:

Lymphatic Drainage of the Rectum: Lymphatic vessels originate within the mucosal and submucosal layers of the rectum. These vessels collect lymphatic fluid from the rectal wall and converge to form larger lymphatic vessels, known as rectal lymphatics. The rectal lymphatics follow the course of the superior and middle rectal arteries and drain into regional lymph nodes.

Pararectal Lymph Nodes: The pararectal lymph nodes, also called the lateral or internal iliac lymph nodes, are a group of lymph nodes located in the pelvic region near the rectum. They receive lymphatic drainage from the rectum, including the upper two-thirds of the rectum. The pararectal lymph nodes play a significant role in filtering lymph and facilitating immune responses within the pelvic region.

Connection to Inferior Mesenteric and Para-aortic Lymph Nodes: The pararectal lymph nodes are interconnected with other regional lymph nodes, including the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes and the para-aortic lymph nodes. The inferior mesenteric lymph nodes receive lymphatic drainage from the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and the upper part of the rectum. Some lymphatic vessels from the rectum directly communicate with the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. From there, lymphatic fluid can flow further up along the para-aortic lymph nodes, which are located along the aorta in the abdominal cavity.

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum, including the involvement of the pararectal lymph nodes, is important for understanding the spread of certain diseases, particularly cancer. Lymphatic metastasis, the spread of cancer cells via the lymphatic system, can occur in regional lymph nodes, including the pararectal nodes. Therefore, the involvement of these lymph nodes is crucial in staging and planning the treatment of rectal cancer.

Clinical Significance

Rectal examinations play a crucial role in diagnosing various conditions affecting the rectum, including tumors, inflammation, and hemorrhoids. These examinations, performed by healthcare professionals, provide valuable information about the rectal and analareasa, aiding in the diagnosis and management of rectal disorders. Here's an explanation of the importance of rectal examinations in diagnosing such conditions:

Tumors: Rectal examinations are essential for detecting tumors in the rectum, including colorectal cancer. During a rectal examination, a healthcare professional can palpate the rectal wall and assess for any abnormal masses or growths. They may also use additional diagnostic tools, such as a sigmoidoscope or a colonoscope, to visualize the rectum and identify any suspicious lesions. Early detection of rectal tumors through rectal examinations can lead to prompt medical intervention, potentially improving treatment outcomes and patient prognosis.

Inflammation: Rectal examinations can help diagnose inflammatory conditions affecting the rectum, such as proctitis or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). By inserting a gloved finger into the rectum, a healthcare professional can assess the rectal mucosa for signs of inflammation, including redness, swelling, or ulcerations. Rectal examinations combined with other diagnostic tests, such as blood tests, stool tests, and imaging studies, can aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory conditions, guiding appropriate treatment strategies.

Hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoids are swollen blood vessels in the rectal and anal areas, which can cause discomfort, bleeding, and itching. Rectal examinations allow healthcare professionals to directly visualize and assess the condition of hemorrhoids. By palpating the rectal area, they can determine the size, location, and severity of hemorrhoids. This information helps guide treatment decisions, such as lifestyle modifications, topical medications, or surgical interventions, to alleviate symptoms and manage the condition effectively.

In addition to their diagnostic value, rectal examinations can provide valuable information about other aspects of rectal health, including the presence of fecal impaction, rectal prolapse, or anal sphincter tone abnormalities. They also offer an opportunity to assess for signs of trauma, infection, or other abnormalities in the anal area.

It's important to note that rectal examinations are typically performed by trained healthcare professionals sensitively and professionally, ensuring patient comfort and privacy. Patients should openly communicate any concerns or discomfort they may have during the examination, and healthcare providers should prioritize patient dignity and informed consent throughout the process.

Note that rectal examinations are a valuable diagnostic tool for detecting and evaluating various conditions affecting the rectum, including tumors, inflammation, and hemorrhoids. Early detection through rectal examinations can lead to timely interventions, facilitating appropriate treatment and improving patient outcomes.

In conclusion, understanding the anatomy of the rectum is of paramount importance for medical professionals and individuals seeking knowledge about digestive health. The rectum serves as the final part of the large intestine and plays a crucial role in the process of defecation. Its location within the pelvic cavity, approximate length, three main sections, curvature, layers of the rectal wall, blood supply, innervation, lymphatic drainage, and diagnostic procedures such as rectal examinations, endoscopic procedures, biopsies, and imaging techniques all contribute to a comprehensive understanding of rectal health and the diagnosis of various rectal conditions. By understanding the anatomy and function of the rectum, healthcare professionals can provide accurate diagnoses, appropriate treatments, and patient-centered care, while individuals can be better equipped to understand their digestive health and seek timely medical advice when needed.

If you have any specific concerns or questions regarding your rectal health, it is always recommended to consult with a healthcare professional. They can provide personalized guidance, perform necessary examinations and tests, and offer appropriate treatment options based on your specific situation. Remember that open communication, regular check-ups, and early detection are key to maintaining good rectal health and overall well-being.

References

Netter, F. H. (2011). Atlas of Human Anatomy, 5th Edition. Elsevier.

Standring, S. (Ed.). (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 41st Edition. Elsevier.

Drake, R. L., Vogl, A. W., & Mitchell, A. W. M. (2014). Gray's Anatomy for Students, 3rd Edition. Elsevier.

Netter, F. H. (2006). Atlas of Human Anatomy: With Student Consult Access, 4th Edition. Elsevier.

Skandalakis, J. E., Skandalakis, L. J., & Skandalakis, P. N. (2002). Surgical Anatomy and Technique: A Pocket Manual, 2nd Edition. Springer.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2018). Anatomy of the Digestive System. Retrieved from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/anatomy-digestive-system

Cancer.net. (2019). Understanding Anal Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/anal-cancer/understanding-anal-cancer

American Cancer Society. (2019). Key Statistics for Colorectal Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

Cleveland Clinic. (2020). Rectal Prolapse. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17473-rectal-prolapse

Mayo Clinic. (2020). Rectal Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/rectal-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20352884

Something perhaps interesting about the gut is that it used to be much larger when we were more ape-like, and then it shrank when we started eating meat, and our brains got bigger. Brains are expensive, and meat provided us with a more nutrient-dense diet but not more calories (also, eating too much meat is toxic). So if the calories we consumed stayed more or less the same, but our brains got bigger, it means something else must've gotten smaller, so we could save calories from that. It appears that the gut is the thing that got smaller, since we didn't need a really big gut now that we ate meat.

Wow, you I have learnt another important point from your comment. Thanks so much friend