Metal extraction

After idk how long a break from the STEM community (I still read some articles despite not writing, okay). I am back to writing because all the exciting parts of my life are now gone and I’m back to studying geochemistry for work again XD

I don’t hate studying it though, I actually plan to take this as my master’s course by 2024/2025. The world needs more geochemists for land surveying and I want to experience fieldwork again since the last time I ever got to do fieldwork was when I was still studying geology (this was actually my first course).

Back to the topic. So this time, it’s finally time to discuss metal extraction! It’s honestly not as exciting as it looks, because if we’re basing on my experience, you either come out extremely dusty or extremely sweaty. It depends on which end of the process you get assigned to, or if you have to oversee the entire process, you’ll get to experience being dusty and sweaty on the same day XD

First and foremost when you get an ore sample, you have to crush/grind it. It has to be in uniform size as much as possible. In most mining companies, they have an analytical mill and a mechanical sieve ready for this. I’m not exactly sure what sieve size they use, but the one we use in a testing lab is at a 40 micron mesh. That’s really fine and it can get dusty whenever you sieve.

younger me using an analytical mill for the first time. That thing scared me, I swear ;;-;; such a violent machine that just keeps eating rocks. See the internal panic in my eyes XD

Next thing is to concentrate it. it’s either you use a hydraulic hose to wash dirt away (this is mostly applicable for high grade ores, the types where you see chunks of metals as soon as you dust off a bit of dust), you use a magnet, froth floatation, or you treat it with chemicals (applicable for refractory ores). Whatever works to get rid of rocks, organic matter or any other interference (we call this gangue) from the metals, actually.

Then the next step? well, that would depend on the reactivity series again. The reactivity series is what I call the holy scriptures of chemistry and I swear, if you do my kind of work, it would be great to know it by heart.

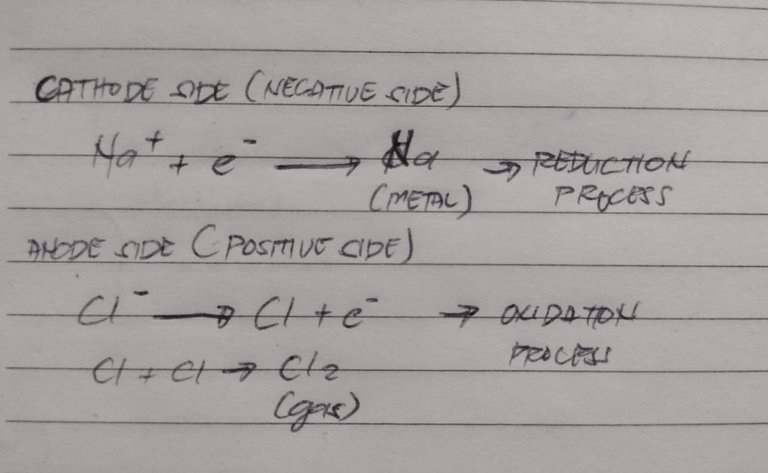

Metals with high reactivity, the ones in the p block of the periodic table, are often the easiest to treat and extract from since they easily lose an electron. In these cases, they often undergo Electrolytic reduction. Here, you’ll have to use a bit of electricity and electrochemistry knowledge. It looks like a lot to study, it is. but the end result is very pure metals and that's often a very sought out commodity. Gases could also be a very nice commodity that can be acquired here, but our focus is metals right now.

sorry for my handwriting again, I'm a bit lazy to type this on MS word, I swear. Anyways, this is the gist of what happens in electrochemistry. You have your metal on the cathode side then gases or halides on the anode side. This method is also used for gold plating and for any metal coating practice, actually but I'll save that for a different discussion.

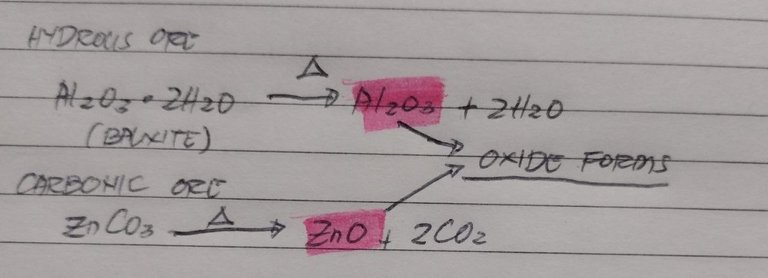

Metals with medium reactivity, calcination and roasting works. Both processes produce an oxide end product, yet the process differs just slightly. For Calcination the process involves heating concentrated ores in a place with limited air. Usually they use a muffled, reverberatory or multiple hearth furnace for this since you can control the air flow rate. The point of limiting the air is to dehydrate the ores. To remove moisture and organic matter without actually melting the metals in the ore. This is a good method when you have hydrous ores or if you have carbonates

my example of common metals that gets reduced through calcination

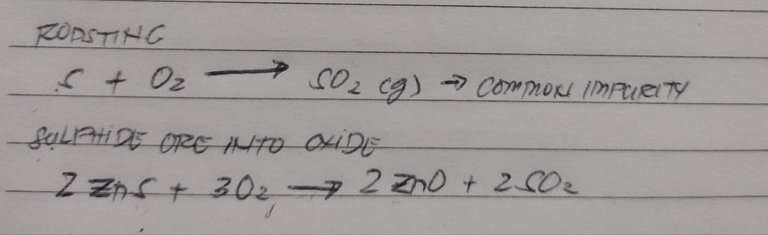

Roasting is the opposite of calcination. When it comes to roasting, you have an unlimited supply of oxygen/free air. It’s also a way to remove organic matter from the ores. This is actually the most common extraction routes for your sulphides

my example of metals that are normally roasted to become oxides

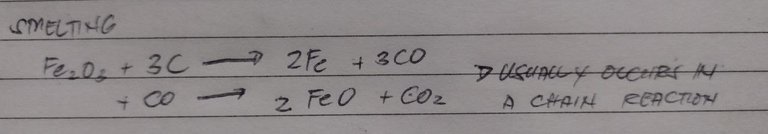

Smelting is also a way to process metals with medium reactivity and the end product is an oxide too. This process is pretty different though in a sense that it uses reducing agents. Normally carbon or carbon monoxide would suffice and this usually occurs in chain reactions. For the process, oxide ores are heated with a carbon source. This could be petroleum coke or charcoal and the reaction would be as follows:

Metals with low reactivity, in other words, the noble metals like gold, silver, platinum and palladium. The only way to extract these metals would be to reduce them with precipitating agents. In most cases, it’s sodium cyanide. Really nasty stuff, I tell you. Luckily, the highly toxic form of cyanide hasn’t been used since the early 1900s (hopefully). In recent journals and newsletters I’m subscribed to though, I see that they’ve been using thiosulfate, thiourea, halide and thiocyanite as cyanide substitutes. In some cases, they’ve been using biogenic cyanide (like pyocyanite) as a leaching agent since it doesn’t take that much cyanide to actually leach out noble metals. Around 100 to 500 ppm suffices to extract from a 1kg bulk sample. Hopefully these newsletters eventually gain applications because it would be nice to see the mining sector take more environmental responsibility (aside from their rehabilitation budget during and after mining operations)

this is all I can elaborate for today XD I still want to do a blog about metal recycling one of these days though.

Sources:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0892687521005653

https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Inorganic_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_and_Websites_(Inorganic_Chemistry)/Descriptive_Chemistry/Elements_Organized_by_Block/3_d-Block_Elements/1b_Properties_of_Transition_Metals/Metallurgy/An_Introduction_to_the_Chemistry_of_Metal_Extraction

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/ore

What do you do with the small quantities of metals in the lab?

!discovery 29

Thank you for your witness vote!

Have a !BEER on me!

To Opt-Out of my witness beer program just comment STOP below

View or trade

BEER.Hey @enforcer48, here is a little bit of

BEERfrom @isnochys for you. Enjoy it!Learn how to earn FREE BEER each day by staking your

BEER.We test it for metal contents. See if it's fit for industrial use. If it's not, we double check if other metals can be taken from it. Whatever our lab results show will tell whether the company wasted resources on dirt or they made a breakthrough with the ores they found

This post was shared and voted inside the discord by the curators team of discovery-it

Join our community! hive-193212

Discovery-it is also a Witness, vote for us here

Delegate to us for passive income. Check our 80% fee-back Program

Your content has been voted as a part of Encouragement program. Keep up the good work!

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for new Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more

Brilliant as usual but of course,I need to ask at least one question! Does all rock contain metal?

When you extract it, presumably you are disentangling elements that haven't been pure atoms since the creation of the earth. You are reversing Gods hard work! You are unbanging the big bang. How awesome is that?

Not all rocks have metals. You can check this with a magnet first. Though you'll mostly get iron, aluminium or zinc from those magnets but that's one way to check. Rock is mostly carbon, organic matter or silica. Ever wondered why a metal detector doesn't just beep everywhere? That answers it too.

And it's not really unbanging the big bang (that would be cool ;;w;;) I think that's what quantum physicists do?

How big are the rocks that you use to extract the metals?

!1UP

It varies. Sometimes as big as a golf ball if it's high grade, like when you find copper or noble metals. Then sometimes as big as a square table. That's usually the case for common ores like limestones or iron ores

You have received a 1UP from @gwajnberg!

@stem-curator

And they will bring !PIZZA 🍕.

Learn more about our delegation service to earn daily rewards. Join the Cartel on Discord.

I had the same reaction when I welded for the first time in the workshop. It was a mess and people were laughing xd.

Never seen a welding machine before but it also looks violent to me. And really hard to operate

It's definitely not for everyone haha. Some of the girls were hilarious while welding. When the sparks form they screamed like they seen a ghost xd. Good times hahaha..

I'd love to see that. Here, the rocks fly out of the mill if you don't cover up the top after throwing the rock in. It becomes a meteor shower, or what my seniors say

That sounds scary haha. I don't want to have rocks in my eyes. I really don't like workshops but it was fun to see people's reaction haha. This happened during our first year in college so it helped to break the ice between freshers.

I somehow managed to weld the welding machine with the metals they wanted me to weld lolz. A friend came in and tried to beat off the metal pieces to help me. it was scary and funny at the same time. The thing is super hot and smoky so If you have allergy then RIP.

Haha for sure the machine also noisy buddy? Like a stone predator whaha

Machine is scary cuz it goes roaarrr

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.