About the Chinese Chess - Xiangqi, 象棋

Dear chess fans and all others!

this week is a break from the Hivechess Friday tournament, so maybe you have time to check out this:

The chinese variant of chess, Xiangqi (象棋), is almost completely unknown in the Western world, even to many chess players, but in China it is extremely popular, in fact the most popular board game over there, also in Vietnam and Taiwan it is frequently played. By the number of players it is even more common than "our" chess (for simplicity just called chess from now on).

It is not known, when exactly it was invented. Probably it originated, like the predecessors of all chess variants, in North India, where this "original chess" was called Chaturanga and was already known since the 6th century AD!

The Chinese variant Xiangqi appeared shortly after that and since the 12th century the rules of the game have not changed! Thus there is an extensive literary fund of especially opening and endgame literature about this game, which even surpasses that of chess! These textbooks often have typically poetic names like "collections of flowers from the peach tree". However, a modern, systematic opening library like we have in chess was created only in 2004.

Unlike chess, in China it is desirable for an educated person with status to be good at Xiangqi!

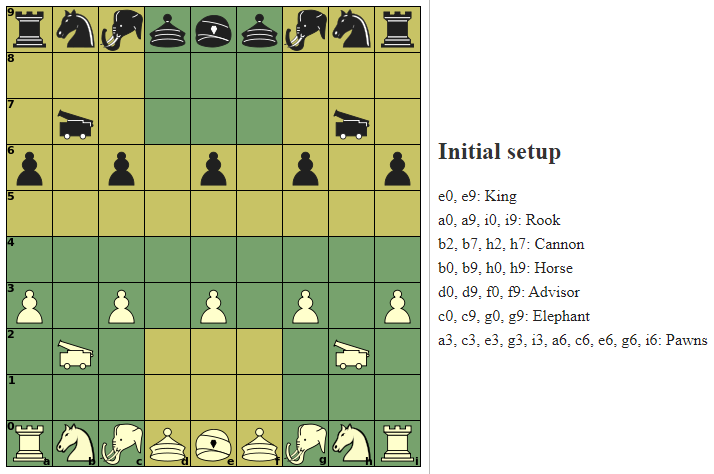

The game board consists of ten horizontal lines and nine vertical lines. Instead of placing the pieces in the squares, they are placed on the intersection points of the lines, like in Go, so that there are 90 possible positions, compared to the 64 in chess. Of note, there are no white and black squares.

The starting position:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/why-you-need-to-learn-xiangqi-for-playing-better-chess

In Xiangqi, two armies symbolically fight against each other. The "palace" or "fortress", 9 positions in each player's base marked by diagonal lines, house the kings (rather called generals) and their two advisors/guards. The so-called "river" divides the board in the middle. It supposedly comes from a river that acted as a border between two hostile empires after they went to war with each other (possibly it was the Battle of the Wei River, in which the Qi Empire was defeated by the Han Empire in 203 BC).

The two opponents each have black (rarely green) and red pieces (red has the first move), and there are not three-dimensional pieces as in chess, but round discs whose meaning is printed in the form of characters - one of the reasons why the game has not yet caught on in the West. There are also Europeanized representations that at least give hints about the possible moves of the pieces (rook, knight), but for the true connoisseur these are frowned upon.

Europeanized visualization (with pieces on fields instead of the intersection points of the lines):

https://www.gnu.org/software/xboard/whats_new/rules/Xiangqi.html

The pieces

General

Unlike in chess, the opponents have differently named pieces, but both - general (black) and marshal (red) - follow the same move rules: one step horizontally or vertically (not diagonally). They correspond - not hard to guess - to the king in chess, but unlike in chess, the general may never leave the palace, so has a total of only nine possible positions. There is also no castling. But there is an interesting long-distance effect - the "death look". The two kings may never face each other freely on a line, without an intervening piece. Obviously, this can become very important in the endgame, because one king can block a whole line to the other (moving the king to a threatened square is forbidden, just like in chess)!

Advisor

The two advisors, also called mandarins or guardians stand in the basic position to the left and right of the general and, like him, may never leave the palace. Since they can only move one square diagonally each, they have only 5 possible positions (the center and the 4 corners of the palace). So the only diagonal lines on the board show not only the palace, but also the move possibilities of the mandarins!

Ministers / Elephants

The two ministers (red) and the elephants (black), usually simply called elephants, are the namesakes of the game ("xiàng" = elephant), which could be also translated as "elephant chess". They are like weak bishops in chess, since they can move diagonally, but only exactly 2 squares, and only if the skipped first square is free. Since they are not allowed to cross the river, they are considered purely defensive units. A strong queen as in chess does not exist in Xiangqi, supposedly reflecting the low status of women in China in ancient times.

Horses

Next to the elephants in the starting position are the horses. These correspond to the knights in chess, but move first one square horizontally and then one diagonally, whereby, as with the elephant, the skipped first square must be free. Therefore, they cannot jump at all.

Chariots (Rooks)

The chariots, initially located at the corners of the board, move in exactly the same way as the rooks in chess. They develop their full strength only during the course of the game (just like the horses), when there are fewer pieces on the board to hinder them.

Cannons

The cannons, which exist only in the Chinese variant, are the most interesting pieces. They move like rooks, but like a catapult they can hit an opponent's piece by jumping over another piece (whether red or black), the so-called "cannon platform" or "screen", over any distance, and also no matter where on the line the cannon platform is located. The strength of the cannons tends to decrease as the game progresses, since fewer and fewer cannon platforms are available. Right from the starting position a player can exchange a cannon for a horse (but that would be not advisable).

Soldiers

The five soldiers correspond most closely to the pawns in chess, but are much more powerful. The number five could stand for the five elements of Chinese philosophy (wood, fire, metal, water and earth). They move one square forward, but as soon as they reach the opponent's side of the river, they are kind of promoted and can also move one square to the left or right (but never diagonally or backwards).

Unlike in chess, they do not capture diagonally, but in the same way as they move, i.e. forward and in the opponents´ half also sideways, which makes them important offensive pieces (you cannot block them simply by placing a piece in front of them like in chess). They are also quite useful as cannon platforms.

Soldiers cannot promote into more valuable pieces after reaching the enemy baseline, supposedly this corresponds to the rigid social hierarchy in China.

Mate / Stalemate

The objective of the game is to checkmate or stalemate the opponent's general. Yes, unlike in chess, stalemate is not a draw, but is considered a victory for the side that can still move.

If a player is checked, there are four reaction options in Xiangqi. In addition to the three that also occur in chess (evade, capture the threatening piece, or place an own piece in between), the fourth option is to remove an own cannon platform so that an opponent's cannon is no longer threatening (see example). If all four options fail, a player is mated and has lost.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiangqi

Example of mate: The red cannon on the top left threatens to hit the general (black) on the next move. Evading the general to the left does not change anything (the cannon can hit this square as well), moving down is not possible because this square is threatened by the red soldier, a diagonal evasion is not possible because the own mandarin is in the way and leaving the palace is not allowed. As a last resort, the own mandarin, which was involuntarily used as a cannon platform by the opponent, could move away, but he is only allowed to move diagonally inside the palace and his only possible move is obstructed by the other mandarin. Therefore mate.

By the way: Giving perpetual check, e.g. to obtain a draw, or other move repetitions - not uncommon in chess - are forbidden in Xiangqi! The repeater must change his plan, because the third repetition leads to a loss! However, the move repetition rules are relatively complicated, because if both players repeat the position, a draw is possible.

A draw by agreement is also allowed.

Game characteristics

Compared to chess, Xiangqi is faster and more aggressive. Due to the fact that the soldiers do not block each other as in chess, there are no closed positions and much less lengthy positional play, but more often a quick king attack. Moreover, with the same number of pieces (16 each), there are 90 squares instead of 64, which makes the game more "open", with a shorter opening phase.

Since, unlike in chess, the kings are in mirror symmetry exactly in the center, there is neither a king´s side nor a queen´s side. Since there are also no queens and bishops, diagonals are generally much less important in Xiangqi than in chess. Instead, the cannons allow for tactical possibilities unusual to chess players, such as the "double cannon" (one cannon using the other cannon as a platform). Typical tactical motifs of chess such as sacrifice, fork, pin or discovered attack also occur in Xiangqi.

More pronounced than in chess, the strengths of the individual pieces can change depending on the phase of the game. Chariots and horses become stronger the fewer pieces are on the board, while cannons become weaker. All three are the active pieces, useful in attack and defense; in contrast, the advisors/mandarins and the elephants, which must remain in their own half, are purely defensive pieces. Soldiers are the third group. The closer they are to the enemy palace, the more important they become. It is said that a soldier in the enemy palace is worth as much as a chariot. Soldiers are also willingly sacrificed for an attack.

Of central importance is to gain and keep the initiative. Whoever has the initiative is in the "upper hand", the defending opponent has the "backhand". It is possible to gain the upper hand from the defense by a sacrifice (or a weak move by the opponent), but it must be well considered in the case of a sacrifice whether the initiative gained compensates for the material lost.

So much for the theory - ready for practice?

Here you can play online against a Xiangqi computer:

http://xahlee.info/chinese_chess/chinese_chess.html

For simplicity, here is the wimp variant with europeanized pieces:

http://www.springfrog.com/games/chess/chinese/

I tried it out and first memorized the meaning of the pieces. With a bit of practice, that went reasonably well. Nevertheless, in the first games I was completely torn apart, because I didn't pay enough attention to the move possibilities. That the horse can't jump and "pawns" can move sideways beyond the river is something you have to remember. Not to mention the sneaky cannon! And the limited move possibilities and restrictions of pieces within the palace makes it much harder for a chess player to cover his own pieces. So patience is required at the beginning!

One of the strongest non-Chinese Xiangqi players is the German chess grandmaster Robert Hübner. Hübner took part in the Xiangqi World Championship in Beijing in 1993 and achieved a highly regarded 36th place among 76 participants!

Xiangqi - popular earlier...

http://www.xqinenglish.com/index.php/en/

...and today as well!

https://www.flickr.com/photos/alidasphotos/48885021342/

Someone suggested that you try unpacking a Xiangqi board in a Chinese restaurant of your town after dinner and playing it with a friend! Within a short time, every employee will come by and want to see that. That would certainly be an interesting experience :)

Who of you has ever played Xiangqi?

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiangqi

https://sites.google.com/site/caroluschess/chess-and-game-variants/xiangqi

https://en.chessbase.com/post/why-you-need-to-learn-xiangqi-for-playing-better-chess

Taken from an old post of mine in German on that former blockchain and brought to Hive and translated using mostly deepl.com

Electronic-terrorism, voice to skull and neuro monitoring on Hive and Steem. You can ignore this, but your going to wish you didnt soon. This is happening whether you believe it or not. https://ecency.com/fyrstikken/@fairandbalanced/i-am-the-only-motherfucker-on-the-internet-pointing-to-a-direct-source-for-voice-to-skull-electronic-terrorism

Oh boy, I need to play this :D

LOVE IT so far, thanks for the tip.

Yay! 🤗

Your content has been boosted with Ecency Points, by @stayoutoftherz.

Use Ecency daily to boost your growth on platform!

Support Ecency

Vote for Proposal

Delegate HP and earn more

yeah I have heard about this game, in fact I watched some players palying these in Tv series, animes, etc...it is so interesting how China adapts everything, who knows, maybe this is the future ahhaha Hive Xiangqi Tournaments lol

Used to play this with my grandfather. Good times.

some time ago I had seen this, honestly I find this way of playing chess interesting, but without a doubt I prefer conventional chess hahaha

Me too. It is hard enough to be good in one.

Great game description and very interesting. I don’t recall hearing about this game right not but I am sure I must have sometime in the pass many years.

I must admit I find many simple things difficult these days, so it would take a hit big screen movie and a TV series for me to learn and play the game. Who knows I probably be a very strong player.🙂

Yes, who knows 😃, you have to try it out!

Hahahaha...I find this very funny, but the game doesn't look easy. But wait! Is chess easy?😄

Haha, yeah, I'm going to need a video tutorial, too.

I bought a 2nd-hand xiangqi board at a YMCA thrift shop during a big book sale, so I read the rules and played a few times against a chinese friend a while back. But it's been so long ago I don't even remember for sure which friend I was even playing, other than he was close to me in age, so I guess it was over a decade ago.

I remember it was fun to play, but I had the same experience as you: it was hard to keep track of all the movement possibilities and the potential movements were less easy to visualize than western chess. Ultimately I didn't think I had the time to invest in it to become decent at it. About 5 years before I had invested a lot of time in becoming tolerably good at weiqi, so I knew how such pursuits could go (no pun intended).

I bet you would easily be a pro if you decide to look back into the game. And as for western chess, How much of your time did you put into it if I may ask?

I didn't invest much time into western chess, less than a year: I was only 12 years old, and I lacked discipline to study hard, I just played for fun. My parents bought me a chess computer (no good players where I lived that I knew of). I played against that some although it often cheated if you started to win because it would overheat when it "thought" too hard, and I read a few chess books, so I got good enough to beat any normal player I met in the area (small town).

I went to one chess tournament, which was fun overall, but it was also where I first experienced that some people are annoying in their competitiveness :-) I think I was rated around 1250 in chess rankings from that tournament, which is pretty weak, but good enough to crush amateurs.

I remember coming back from the tournament (my parents had to take me as it was a couple hours away from where I lived) and I couldn't make my brain stop thinking about chess positions, which was a little disturbing as it was the first time I didn't have full conscious control over my thoughts.

I was also very ambitious then, so if I spent time at it, I wanted to become among the best, and it looked like I would have to invest too much of life to potentially reach that goal (and it seemed from my brief reading on the subject that many of the strongest chess players were a bit crazy). So I gave up chess very early and never really played more than a few games after that. Nowadays, I'm less competitive, so I'm comfortable to learn something and just be "good" at it, but I found I liked go more than chess.

I played both games at very different ages, so maybe I would enjoy chess more this time if I went into it seriously. My problem as a kid was that I didn't like it when I couldn't find any obvious good move (in go this is never a problem, it is just a case of having to decide among too many good moves).

This reminds me of what Albert Einstein once said "Chess holds its master in its own bonds, shackling the mind and brain so that the inner freedom of the very strongest must suffer.”

Chess can be very addictive and strong, for you to have this experiences, it really tells you love the game and you had/have Passion for the game. I hope to see you create some time and join our competitions here on Hive. Thanks for sharing your story👌

Yes, it is less easy to visualize because we don't have enough practice. But it gives me an interesting insight when it comes to blindfold chess.

I think blindfold skill is necessary to become truly good at any of these games, because the advantage comes from person who can see the board several steps into the future, which means they have to visualize positions they can't see. I guess that's why all the grandmasters have this ability.

Apparently the way it works can be described by the way we read. New readers (children) read and see character by character, and eventually syllables. Advanced readers just recognise words like they would a photo. So when you look at the word "Chess", you just see "Chess" as a picture that you recognise without having to read it. Speed readers can see entire sentences or even the following sentence in their heads before reading it out.

Those chess moves are easy for the grandmasters to visualise as they're just words or sentences to them, so they can just see them without having to think much about it.

I saw the analogy in a book I was reading about the brain and cognitive ability. Interesting stuff.

It makes sense. I've heard some people argue that the way the brain works when you play chess is very similar to when you use spoken language. So they argue that chess is a language and that would explain why children who practice chess develop better language skills. These are things I have read and remember from memory. Right now I can't cite any specific source.

On the other hand, besides the ones you pointed out, I think there are also other cognitive concepts and analogies involved here to interpret and explain the way chess players do when they play chess blindfolded or not, like intuition, you know, the ability to do things without putting a lot of conscious effort into it. It's like some tasks in daily life that you do without paying much attention because after enough practice you can do them automatically, like a routine. Chess players who are very well trained and reach a certain level can play high quality games seemingly without effort. The moves simply come to their mind and it is something easy to notice, for example, when they play bullet chess online. Of course, we can argue that this happens to some extent to players of different levels, but in advanced players the skill is remarkable and extends to different aspects of the chess game, and so on.

I think this is to some extent true. After I played games of go, I could often reconstruct the moves of the games afterwards, and it was mainly because me and my opponent were generally making high probability (i.e. relatively good) moves. Similarly, you could view words as high probability arrangements of letters, which is the underlying reason we can recognize a word right away and remember its spelling, whereas it is more difficult to remember a random string of letters.

But where this would probably fall apart is if an expert played a total amateur who was making nearly random moves at times. Such a game board wouldn't be encodable into a high probability subset of "words".

So, the question I don't have the answer to is, could a go master recall such a game? I can't say for sure, but my suspicion is "yes", which would weaken the word recognition theory somewhat. So my guess is that they have a few skills working in concert: 1) the ability to recognize and recall high probability patterns, 2) a stronger ability to remember raw go board positions, and 3) they may attach extra significance to a stone's position such as difficulties associated with its placement such as "that stone will break my ladder attack" that make it easier to recall the placement relative to the other stones on the board.

I agree, blindfold chess is always recommended to improve calculation and visualization. I've heard about a few old psychologists who have written about it.

Hey mate, sorry to jump in off-topic.

Do you mind reviewing and supporting the Hive Authentication Services proposal? That would be much appreciated.

Your feedback about the project is welcome too.

Thank you.

Done :)

Sounds very interesting!

Thank you for your unfailing support, really appreciate it! 👍

I'm hearing it for the first time, and it sounds really complicated and difficult, it has more differences than similarities than chess, But I'm gonna learn it to help broaden my social knowledge. Thanks for sharing.

I've heard of this game. We have to give it a shot. Maybe there is an equivalent for Lichess out there.

On the other hand, I remember I read a chess news a long time ago about Kasparov facing a strong player of an alternative chess (maybe it was this, Xiangqi) and Kasparov was able to beat the guy in that game too!! even though the guys was a professional player. I hope I'm remembering it well, I was a bit lazy to look up again, so don't take my word for it :P

Wow. To me it's very difficult to believe this since chess is newer, but far more popular. I need to learn more about this. Is it from wikipedia where you heard this?Yes, Wikipedia and this:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/why-you-need-to-learn-xiangqi-for-playing-better-chess

I know, hard to believe, but on the other hand, in numbers more people play Xiangqi!

But no Xiangqi tournament for me, too frustrating.

I think the same applies here: chess is a way more international game, it has a huge chess federation and many business work around chess as a sport and a subject of entertaining. In that sense, chess is more popular.

I'll look up the statistics thing about the number of publications for both games. It's interesting.

Heeey @stayoutoftherz , and very nice to Hive you! 🙃

I'm so glad you exhumed this "old" publication of yours, translated it and posted it again! Mahjong and Go were till now the only Chinese boardgames I knew of; thanks for widening my culture!

Do you intend to launch anytime soon a HiveXiangqi Monday tournament?

LOL, no! It would be really fun, but I don´t have that much time. But anybody could start this, maybe you?

Hehehe, it's a nice suggestion! I'm first going to try to get used to the Xiangqi rules - thanks for the websites' url to practice it 😃.