Patagonia y sus orígenes, otra historia de piedras ESP-ENG

Pocos años atrás se tomó una decisión que provocó no pocas controversias: la provincia de La Pampa había sido aceptada como parte de la Patagonia.

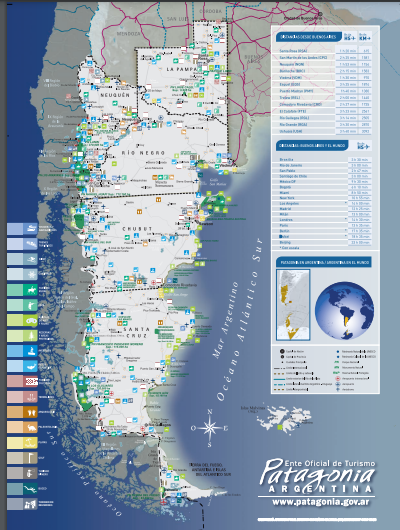

Desde que se denominó de tal manera a toda esa vasta región del sur de la Argentina, su límite norte estaba dado por el río Colorado, es decir incluía a las provincias de Río Negro, Neuquén, Chubut, Santa Cruz y Tierra del Fuego. Esa región tiene algunas leyes y reglamentaciones especiales que hasta ese momento no incluían a La Pampa; siempre existe esa cuestión de pertenencia que las costumbres exacerban un poco y aceptar de un día para el otro a otra provincia no fue del agrado de muchos.

Pero la incorporación y más precisamente los fundamentos de su inclusión llamaron mi atención y me puse a leer sobre la teoría por la que se tomó tal decisión. Resultó ser apasionante y voy a compartirla aquí tratando de no incluir demasiada terminología y considerandos científicos.

En el segundo decenio del siglo XX el geofísico de origen alemán Alfred Wegener planteó la teoría del desplazamiento de los continentes, principalmente basándose en las formas de África y América que parecían encajar casi a la perfección. Por supuesto como toda teoría innovadora fue descreída por la mayoría de sus colegas y recién para la década de 1960 su idea de la deriva de los continentes comenzó a aceptarse basada principalmente en investigaciones más modernas. Como consecuencia se supuso que toda América del Sur constituía un solo bloque que se separó de Pangea (nombre que se da al bloque primigenio que unía a todos los continentes en uno solo) hace unos 300 millones de años formando junto a los continentes del hemisferio sur lo que se conoce como Gondwana, mientras que los del hemisferio norte recibieron el nombre de Laurasia.

Muchos científicos han estudiado y continúan haciéndolo al presente, la forma y las rutas que tomaron los continentes en su deriva.

Fotografía cedida por HOG @hosgug

En los últimos 30-35 años, varios científicos de diversas especialidades de nuestra región se han planteado dudas respecto a la posición paleogeográfica de la Patagonia, algunos sostienen que siempre ha estado unida al resto del continente mientras que otros plantearon la posibilidad de que fuera un bloque que se desprendió de Antártida y en su deriva chocó y se unió con posterioridad al resto de América del Sur. El mayor defensor de esa teoría fue Víctor Ramos, investigador del Conicet (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de la Argentina), quien en el año 1984 presentó sus estudios durante un congreso en la ciudad de Bariloche, la llamó “Patagonia alóctona” es decir que tiene un origen y lugar diferente al resto del continente.

Por supuesto tuvo un gran impacto; al igual que lo que ocurrió con Wegener muchos años antes, en los primeros tiempos la teoría fue descreída por la comunidad científica local. Luego de transcurridos más de 20 años, prácticamente el 80% de esa misma comunidad concuerda con la hipótesis de Ramos.

Lo que llevó a Ramos a desarrollar su teoría fue la observación de un arco volcánico cuya erosión solo dejaba al descubierto las raíces de un conjunto de montañas separadas y paralelas en un principio a la Cordillera de los Andes pero que luego cruzaban perpendicularmente hacia el este desde Bariloche hasta Sierra Grande. En ese momento pensó que debía existir al norte una zona de sutura que separaba a Gondwana de la Patagonia. Inclusive llegó más allá al proponer que las Sierras de la Ventana que se encuentran en el centro de la provincia de Buenos Aires podrían ser consecuencia y efecto del choque de ambas masas.

Fotografía cedida por HOG @hosgug

El geólogo inglés Robert Pankhurst y el argentino Carlos Rapela, director del Centro Científico y Tecnológico de La Plata (CCT) abonaron a esa misma teoría de la colisión de la Patagonia con el hasta entonces extremo austral de América del Sur.

Existen varias pruebas y hechos que apoyan esas teorías, algunas demasiado complejas, sin embargo, una bastante concluyente indica que la fauna de invertebrados fósiles presenta una desconexión con la hallada en el Norte de la Argentina, lo que hace suponer que la Patagonia si era un bloque aislado del resto de Gondwana.

Por otra parte, algunos organismos marinos hallados en Patagonia y cuyos primeros indicios datan de hace más de 500 millones de años, indican un clima más frío que los registrados al norte del país, eso apoyaría la teoría del desprendimiento del bloque de la Antártida.

Fotografía cedida por HOG @hosgug

Mucho de esto se tuvo en cuenta para decidir que la Pampa forma parte de la Patagonia, espero no haberlos aburrido con la historia.

Fuentes:

CONICET La Plata Centro Científico Tecnológico

CONICET Organismo dedicado a la promoción de la ciencia y la tecnología en la Argentina

Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio

English Version

A few years ago, a decision was made that caused quite a few controversies: the province of La Pampa had been accepted as part of Patagonia.

Since this vast region of southern Argentina was named in such a way, its northern limit was given by the Colorado River, that is, it included the provinces of Río Negro, Neuquén, Chubut, Santa Cruz, and Tierra del Fuego. That region has some special laws and regulations that until then did not include La Pampa, in addition, there is always that question of belonging that customs exacerbate a bit, and accepting another province from one day to the next was not to the liking of many.

But the incorporation and more precisely the grounds for its inclusion caught my attention and I began to read about the theory on which such a decision was made. It turned out to be exciting and I am going to share it here trying not to include too much scientific terminology and recitals.

In the second decade of the 20th century, the German-born geophysicist Alfred Wegener put forward the theory of the displacement of the continents, mainly based on the shapes of Africa and America that seemed to fit almost perfectly. Of course, like any innovative theory, it was disbelieved by most of his colleagues and it was not until the 1960s that his idea of the drift of the continents slowly began to be accepted, based mainly on more modern research. Based on this, it was assumed that all of South America was a single block that separated from Pangea (the name given to the original block that united all the continents into one) about 300 million years ago, forming together with the continents of the southern hemisphere what is known as Gondwana, while those in the northern hemisphere were called Laurasia.

Many scientists have studied, and continue to do so to this day, the shape and routes taken by the continents as they drifted.

In the last 30-35 years, several scientists from various specialties in our region have raised doubts regarding the paleogeographic position of Patagonia, some maintain that it has always been linked to the rest of the continent while others raised the possibility that it was a block that broke away from Antarctica and in its drift collided and joined the rest of South America. The greatest defender of this theory was Víctor Ramos, a researcher at the Conicet (National Council for Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina), who in 1984 presented his studies during a congress in the city of Bariloche, calling it "Allochthonous Patagonia" say that it has a different origin and place than the rest of the continent.

Of course, it had a great impact, just like what happened with Wegener many years before, in the early days the theory was disbelieved by the local scientific community. After more than 20 years have elapsed, practically 80% of that same community agrees with the Ramos hypothesis.

What led Ramos to develop his theory was the observation of a volcanic arc whose erosion only exposed the roots of a set of separate mountains that were initially parallel to the Andes Mountains but later crossed perpendicularly to the east from Bariloche to Sierra Grande. At that time he thought that there must be a suture zone to the north that separated Gondwana from Patagonia. He even went further by proposing that the Sierras de la Ventana, located in the center of the province of Buenos Aires, could be the consequence and effect of the clash of both masses.

The English geologist Robert Pankhurst and the Argentine Carlos Rapela, director of the Scientific and Technological Center of La Plata (CCT) subscribed to that same theory of the collision of Patagonia with the until then the southern tip of South America.

There are several tests and facts that support these theories, some too complex, however, one quite conclusive indicates that the fauna of fossil invertebrates presents a disconnection with that found in the North of Argentina, which suggests that Patagonia was a block isolated from the rest of Gondwana. On the other hand, some marine organisms found in Patagonia and whose first indications date from more than 500 million years ago, indicate a colder climate than those registered in the north of the country, which would support the theory of the detachment of the Antarctic block.

Much of this was taken into account to decide that the Pampa is part of Patagonia, I hope I have not bored you with the story.

Sources:

CONICET La Plata Scientific and Technological Center

CONICET | Organization dedicated to the promotion of science and technology in Argentina