Measurement and signatures intelligence (MASINT)

Intro

I'm stuck hallway through a masters program in Intelligence Studies (spy, not IQ). I'm sharing some of that work.

The elephant in the room - Copypasta for this series

I doubt there is anybody left in the country that has any trust at all in the IC. I certainly don't, and that sometimes show up in my work.

I do think there is still value to you the reader here. Espionage is like informationwar or a gun. it is a tool to use when necessary. While the everyday Hiver doesn't have a taxpayer-filled bag of money to support their own agency, there is a lot of education that is valuable to me (and I think to you). Part that is if you can explain where the IC has fallen from where it should be, your arguments against it, or for its reform. or for its disbandment will carry more weight.

And on to the show

Discussion Post

Categorize the challenges facing the MASINT community and analyze some of the implications of these challenges for the future. Make sure you place your discussion within the context of the literature.

From the beginning of human history, humans have tended to use “magical” thinking to explain the world around them. Frazer (1985), in The Golden Bough, describes this as appealing to supernatural forces for benefits by imitating or coming into contact with such forces. The other side of human thinking is critical thinking, or trying to determine cause and effect, of which scientific method is a key component. Historian Paul Johnson (1977), in Enemies of Society, argues that the first societies to begin using scientific method and critical thinking on a societal level were the Classical Greeks (and I would say that the argument can still be made today that too many humans rely on “magical” thinking as opposed to matching cause to effect...”critical theory” coming foremost to mind).

Goodman (2009) ties this into the intelligence field with a discussion on the scientific intelligence conducted by Thucydides. According to Goodman, it is important to not only understand when an enemy attacks, but the exact method of his attack, which means understanding the technology he uses. Possony et al (1997) argue that technology can be the crucial element in decisive warfare.

Goodman then goes on to examine several challenges facing the MASINT discipline, although he refers to it as “scientific and technical intelligence” (STI)

- Since it covers some of the most highly classified information available, there are severe restrictions placed on who has access. This leads me to ask, “What happens when you don't have any competent techs who can get the necessary clearance?”

- This leads Goodman to discuss whether such technicians should be full time government employees, or should they be current in research as university/private research employees. This echoes a lot of the argument that occurs over the privatization issue overall.

- A corollary posed is whether you want scientists trained in intelligence, or intelligence operatives trained in scientific method.

- Part of the estimation process is by using past actions to judge current actions which can not be verified otherwise.

Goodman frames these challenges against the purpose of MASINT, and points out that the concepts of CAPABILITY and INTENT must be estimated to gauge the proper level of THREAT. Intentions are further broken down into strategic intentions and tactical intentions, while capabilities can be sorted into theoretical and practical capabilities. All of these factors must be calculated while estimating THREAT.

A final challenge which Goodman doesn’t discuss specifically can be seen in the four cases which he presents. All four examples show a lack of critical thinking in how the intelligence estimation was framed.

Lynn (2012) supports Goodman’s ideas with a discussion of two “fundamental problem areas”. The first problem noted is the time requirement to produce good MASINT intelligence. The second echoes Goodman’s concerns regarding the composition of MASINT “operators”. The recommendation for dealing with this issue is better communication and education of MASINT capabilities. Mugavero et al (2015) also highlight additional challenges. First, that MASINT must be kept up to date with technological advancement to be of use, and secondly that MASINT must be integrated with complimentary intelligence to be of use.

Now THAT is definitely critical thinking!

References:

Frazer, S. J. G. (1985). Golden Bough (Abridged edition). Collier Books Publishing.

Goodman, M. S. (2009). Jones’ Paradigm: The How, Why, and Wherefore of Scientific Intelligence. Intelligence and National Security, 24(2), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684520902819651

Johnson, P. (1977). Enemies of society (1st American ed edition). New York: Atheneum.

Lynn, C. (2012). Making the Most of MASINT and Advanced Geospatial Intelligence. USMC Command and Staff College, Quantico, VA.

Mugavero, R., Benolli, F., & Sabato, V. (2015). Challenges of Multi-Source Data and Information New Era. Journal of Information Privacy and Security, 11(4), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15536548.2015.1105617

Possony, S. T., Pournelle, J., & Kane, F. (1997). The Strategy of Technology. Retrieved December 12, 2019, from Www.jerrypournelle.com website: https://www.jerrypournelle.com/jerrypournelle.c/sot/sot_intro.htm

Notes

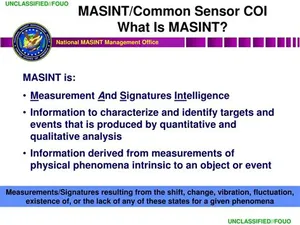

As we move into Week Six, we will explore another technologically based intelligence collection discipline: Measurement and Signatures Intelligence (MASINT). MASINT collection represents the technological high-ground amongst the intelligence collection disciplines. It is also known as the “scientific discipline.” All objects, whether living or inert, exhibit some form of distinct characteristic that can be measured by its properties. These distinct characteristics, known as “signatures,” offer the potential for detection and tracking to support intelligence activities. The MASINT community seeks to measure various phenomena and develop a database of signatures to support detection, identification, and tracking of objects that have intelligence value. MASINT collection activities often times provide the technological edge to support strategic and tactical efforts. MASINT is used to support a broad set of mission ranging from treaty verification and counter proliferation efforts to providing remote sensing capabilities on the battlefield. While MASINT collection activities do represent a distinct technological edge, there are also some limitations in the sense that a significant Research and Development (R&D) cost is necessary to actualize these capabilities as well as possessing some lengthy collection, processing, and exploitation issues for some of its capabilities.

Lesson Objectives

Students will be able to:

Examine the role of Intelligence Collection as it applies to Indications & Warning (I&W) and preventing surprise.

Distinguish the strengths and limitations of various intelligence collection disciplines.

Specific Topics of Discussion

In this lesson, we will discuss:

The strengths and limitations of MASINT activities.

The challenges facing the MASINT community within the modern-day Intelligence Community.

Key Learning Concepts

Key Learning Concept 1

Measurement and Signatures Intelligence (MASINT) is a technologically sophisticated collection discipline that seeks to detect, identify, and track the distinct characteristics of objects, known as “signatures,” to derive key insights and intelligence value. MASINT collection efforts focus on distinct areas: nuclear, chemical, and biological features; emitted energy (e.g., nuclear, thermal, and electromagnetic); reflected (re-radiated) energy (e.g., radio frequency, light, and sound); mechanical sound (e.g., engine, propeller, or machinery noise); magnetic properties (e.g., magnetic flux and anomalies); motion (e.g., flight, vibration, or movement); and material composition. Measuring object parameters and developing a database of signatures requires significant and upfront Research and Development (R&D) efforts to actualize these activities

Key Learning Concept 2

MASINT collection activities represent a key advantage to the U.S. Intelligence Community. As an intelligence collection discipline, the employment of MASINT represents a niche capability that supports both strategic and tactical objectives. MASINT collection can provide confirmation to support treat compliance issues to remote sensing on the battlefield. Despite these advantages, MASINT also possesses some limitations. Measuring distinct parameters for a variety of objects and data basing signatures that can be tracked requires a significant R&D effort and cost. Additionally, latency in collection, processing, and exploitation efforts can result in delays. Given the nature of the modern threat, these delays can reduce the efficacy of MASINT collection depending on the situation.

Goodman, Michael S. “Jones' Paradigm: The How, Why, and Wherefore of Scientific Intelligence.” Intelligence and National Security 24. No.2 (2009): 236-256. Click here.

ABSTRACTScientific intelligence was coined during World War II, yet despite its ageand relative importance it has not received the attention it should have. This issurprising given the recent and growing interest in WMD programmes. This article setsout the main components of scientific intelligence, seeking to explore how scientificintelligence has been defined, how it operates, and contemplates the key issuesinvolved. In doing so it aims to set an agenda for future research into this crucial area

I conceived Scientific Intelligence, with its constant vigil for newapplications of science to warfare by the enemy, as the first watchdog ofnational defence; and to be a good watchdog it is not sufficient to detectthe approach of danger – you must bark at the right time: not too early,for then your master becomes dulled to danger by too much barking,nor too late, for he may then be overtaken by disaster; and you mustnot bark at false alarms

R.V. Jones, ‘Scientific Intelligence’,Journal of the Royal United Services InstitutionXCII(1947) p.354.World War II is notable for the wholesale application of science towarfare. While this, in a sense, was merely the continuation of a trend thathad begun with World War I, there were two crucial differences. Firstly, thescale involved: weapons programmes began to use scientists more than everbefore. Indeed, one author has claimed that Allied victory was due to theirbetter harnessing of science than the Axis powers. Secondly, intelligencebecame far more preoccupied with knowing what the enemy was up to.

Scientific intelligence collection can in a sense be split into two categories:it is necessary to gather intelligence on the development of a particularweapon; but it is also necessary, where applicable, to be able to detect theactual testing of such a weapon.

intelligence during the cold war can, in asense, be seen more appropriately as concerned with long-term targets.During peace there is far less interaction with intelligence targets, and thereis therefore the added problem of having to avoid antagonizing the enemy,for as Churchill succinctly put it, ‘war simplified some of our problemsbecause in war you don’t have to be polite, you just have to be right’.

For scientific and technical intelligence the end of the cold war, with itssudden disappearance of the principal antagonist, did not leave the samevacuum apparent in other types of intelligence. The expanded threat ofnuclear, biological and chemical weapons’ proliferation merely served toincrease the work of intelligence agencies. Yet with this the means ofprocuring reliable information also diminished. These types of weaponsprogrammes became the most secret aspects of highly impenetrable, despoticregimes.

ost-1945 STI has hadto concentrate far more on material manifestations of tests to actually finddefinitive proof of a weapon’s existence. Such intelligence has been termedby Michael Herman as ‘observational intelligence’, that is, the type ofinformation that is ‘relatively ‘‘hard’’ on physical entities such as militaryhardware, but need[s] more inference in discerning the target’s intentions or otherwise reading its mind’

One of the earliest academic analysts of the intelligence machinery, KlausKnorr, argued that the role of an intelligence organization is ‘not only toestimate whether or not a threat exists, but to assess its precise nature’

While the collection of information relevant to scientific and technicalintelligence is undertaken by all components of the intelligence community,the analysis of such information is a far more compartmentalized affair.2

ME: CHALLENGE

- The problem with STI is, in a way, the nature of the subject matter itself. Itdeals with some of the most important – and thus highly classified –information available. As such there are severe restrictions placed on whohas access to material.

ME: CHALLENGE

What happens when you dont have any competent techs who can get the necessary clearance?

A further problem, and one for which there is no definitive answer, is theactual composition of STI departments and branches. Undoubtedly what isrequired is competent scientists, technicians, engineers, etc. who are capableof evaluating information on foreign developments to gauge progress. Yetherein lies the problem. Should such figures be seconded part-time fromuniversities and government research laboratories, or should they be full-time STI employees? There are virtues to both: a university scientistseconded will, in theory, be far more up to date with current research;similarly, a technician seconded from a government research laboratory willbe abreast of the latest indigenous developments. At the same time, though,it is far more problematic to be brought into intelligence, spend 2–3 years ona subject and then leave again, because it is too difficult to determine long-term trends or to get used to the level of scientific research and infrastructurein a foreign country. On the other hand, someone who has spent their careerstudying the weapons programme of Communist China may, in the parlanceof such things, go ‘native’ and lose any sense of open-mindedness. It is fair tosay that all these factors have occurred at one time or another. A final andrelated consideration is whether it is better to have trained scientistsindoctrinated into intelligence, or trained intelligence officers indoctrinatedinto science. Clearly what is needed a mixture of all these elements.

ME: CHALLENGEDuring the cold war it was standardprocedure for intelligence estimates to differentiate between ‘intentions’ and‘capabilities’. While these notions, if not the terms themselves, had existedduring the war, it was very different because it was confidently assumed thatwhenever a weapon system was ready it would be used: therefore there was adirect linear relationship between the two. During the cold war this was notquite so clear-cut, because a capability did not equate to an intention, or viceversa. In producing STI analysis it is absolutely crucial to comprehend boththese two terms and the often amorphous relationship between them.

Now we can break this simple statement up: by commentingthat ‘Saddam would like to have an atomic bomb’, we can identify astrategic intention, that is a long term goal. By saying he ‘would use if it hecould’ we can identify atactical intention– that is an operational aim.Finally, by posing the question ‘but could he acquire one’ we can identify thecapability angle.

An understanding of capabilities and intentions is crucial to anyintelligence assessment. During the cold war, the traditional equation that

THREAT=CAPABILITY+INTENTwas considered adequate.

In contemporary times, with the increased andlargely American desire for pre-emption, this can be re-written so that

THREAT=CAPABILITY+/-INTENT

Some people write this equation as Threat=Intent x Capability, therefore if one is absentthe other is nullified. But does the lack of either mean there is no threat?

ME: CHALLENGE must determine both capability and intent, and balance out both to determine actual threat

Intentions, unlike capabilities, are far more difficult to discern. This isparticularly the case when trying to gauge whether a leader is rational or not;to assume otherwise would imply that any number of options are plausiblebecause the leader is, simply, unpredictable. This poses tremendousdifficulties of course, for not only are leader’s decisions influenced by anynumber of extraneous factors, but often we are not talking about democraticleaders, but instead dictators, despots or megalomaniacs. Despite this,assessments can be made, often based on such traits as past behaviour,sociological conditions, cultural characteristics, economic issues, internalpolitical pressures, strategic motivations, psychological profiles etc. Putsimply, estimating intentions is therefore a far less tangible and morespeculative process than estimating capabilities.33Yet it is also important todistinguish between different types of intention: we can talk in terms of astrategicintention – that is the desire to acquire a weapons programme in thefirst place – and atacticalor operational intention – the desire to actually usea weapon once acquired.34While these may be related, the former does notnecessarily imply the latter

We can split ‘capability’ into two then, because atheoreticalcapability is avery different prospect to apracticalcapability, yet the two do notnecessarily follow on sequentially. In other words a state may have thetheoretical knowledge to construct a ballistic missile weapon but lack thepractical means to do so. Similarly, a country may have a finished biologicalagent, but lack the prerequisite means of delivery (or vice versa). At the sametime, though, a state may, on the other hand, have the practical means tobuild a weapon, but lack the actual scientific know-how to do so, and thiscan be in terms of the inability to interpret theoretical plans or simply notknowing what to do next.

In fact this is precisely what happened with therecent Iraq WMD fiasco, that in the absence of any good intelligenceestimates were produced based on past and current patterns of Saddam’sbehaviour: therefore his seemingly deliberate obfuscation was taken asimplying he was still seeking such weapons, because this is what he haddone in the past. In doing so the fact was seemingly precluded that Saddamhimself could have been misled by his scientists into thinking that he hadsome sort of capability. In this context the words of David Kay, onetimechief American weapons inspector in Iraq, are particularly prophetic: ‘wemissed it [Iraqi WMD] because the Iraqis actually behaved like they hadweapons . .. and we weren’t smart enough to understand that the hardestthing in intelligence is when behaviour remains consistent underlyingreasons change’.

EstimatesSuch processes highlight the importance of ‘estimating’, a concept that isvital to the intelligence process. Sherman Kent, the American ‘father’ ofstrategic intelligence within the CIA pointedly remarked that ‘estimatingis what you do when you don’t know’.39While this may be rather statingthe obvious, it does highlight the strong element of subjectivity within theestimating process. If it is assumed that objectivity is impossible to attain,then instead ‘ambiguity ‘‘legitimizes’’ different interpretations’, for asMichael Handel has suggested ‘all analysis must inevitably be based onpre-existing concepts’

ME: CHALLENGE

but you have to fill in the blanks, or prpare for ALL possible threats

- Case 1. We Develop Weapons – They Develop WeaponsThis is the most frequent scenario and, as the title suggests, occurs whenboth sides develop comparable munitions. However, even within thisthere can be debate, because while the ultimate aspiration might besimilar, both nations may take completely different routes to achieve it. Agood example is the development in the 1950s of the hydrogen bomb. Fora number of years the Americans floundered and could not work out howto ignite the thermonuclear fuel involved. Finally, in 1951, they stumbledupon the successful path. Prior to this point US intelligence agencies hadassumed that because they could not crack the problem, then neitherwould the Soviet Union be able to. Once American scientists solved ithowever, intelligence estimates changed accordingly and credited the

Perhaps the greatest example of this is the Enigma machine: the Germans tried to crack it,couldn’t, and so assumed that neither could anyone else.

ME: Challenge

lack of critical thinking…

Case 2. We Develop Weapons – They Don’t Develop WeaponsAttempting to prove that something exists is one thing, but it is virtuallyimpossible to disprove existence: as Donald Rumsfeld made famous in hisrecent remark over Iraq: ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’.

Case 3. We Don’t Develop Weapons – They Develop WeaponsIn a sense this is the most troublesome case. It can come about either becauseit is decided not to develop a weapon (for whatever reason), or becausetechnical difficulties are insurmountable at the R&D phase. A good exampleof the former category, where analysts are being asked to consider infor-mation on a programme about which they have no indigenous information,occurred with the Soviet tank programme. Information, often conflicting,was amassed by the Defence Intelligence Staff, whose job it was to produceestimates. At some stage the decision was taken that all the intelligencereferred to one particular tank system, and the resulting estimate was of astrange new contraption. As it was, the information referred to two differenttank systems, and the DIS estimate was a bizarre hybrid creation of the two

Case 4. We Don’t Develop Weapons – They Don’t Develop WeaponsThis has similarities to the other cases but is still unique. Once more theproblem of proving a negative is evident – that a weapon isnotbeing built –as is the difficulty in assessing information about which you have no directexperience

How do all these factors contribute to the production of intelligenceassessments? Rarely ever will an STI estimate be based solely on science, butwill invariably include estimates of economics, internal politics, interna-tional politics, etc

If we deconstruct the topic, then STI estimates really aim to do two things:1) evaluate and assess current progress (including past efforts); 2) predictfuture development. In a sense these two are directly related, because it isimpossible to gauge future actions without looking at present and past actions

ME: filed under no shitOne difficulty in producing STI estimates lies in semantics or wording,something Lord Butler identified with some bemusement in his report. Inreading numerous JIC reports Butler found a wide spread of phrases,including: ‘intelligence indicates’, ‘intelligence demonstrates’, ‘intelligenceshows’, ‘we assess that’, ‘we judge that’, ‘we believe that’. Indeed, Butlerfound that ‘some readers believe that important distinctions are intendedbetween such phrases’, whereas ‘in reality [there is] no established glossaryand that drafters and JIC members actually employ their naturallanguage’.5

ME: CHALLENGEA standard dichotomy in the production of estimates is finding the narrowdividing line betweenpossibleandprobable, betweenworst-caseandlikely-caseassessments, and between what a nationcando and what theywilldo.

ME:returns to balance of estimating intention and capability.In terms of producing anestimate itself and despite all the caveats and issues discussed above, thecentral ingredients will be an evaluation of the enemy’s capabilities andintentions. As has been mentioned, finding the precise relationship betweenthese two is no mean feat, yet it is possible to identify an approximateformula in gauging a threat:HIGH THREAT¼high likelihood vs high impactLIMITED THREAT¼low likelihood vs high impactLIMITED THREAT¼high likelihood vs low impactLOW THREAT¼low likelihood vs low impact

While it is beyond the aims of this paper todefine these (not least because this moves beyond the responsibility of STI), itis worth differentiating between apotentialthreat and anactualthreat.

Estimating postfacto is different to producing a predictive forecast. Any deliberation will depend once more on the starting supposition: is it to question whether anevent was natural or artificial? Is it to see which countriescouldhavecarried out an attack? If we preclude this first point and assume theoutbreak was artificial and deliberate, then we are faced with two verydifferent assumptions: is it a question of keeping an open mind to seewhere the evidence leads to, or is it a question of proving that country Xdid carry out the attack or that country Y could not have carried out theattack? This poses a similar dilemma to the criminal court, whereby in onecountry the defendant is innocent until proven guilty, but in another he isguilty until proven innocent. The question is where does the onus ofresponsibility lie?

In many respects the difficulties in intelligence estimation are inherent in therelationship between intelligence producers and intelligence consumers. Inthis way John Prados has written that ‘ideally intelligence informs policy.Through intelligence, decisions can be made on the basis of reasonablyaccurate and objective knowledge of existing conditions

ME: ROFL

politicians are reatrds and liars

Scientific and technical intelligence has a more varied role than otherforms of intelligence when impacting on the policy realm. This function canbe split into three:1) Policy response;2) Countermeasures;3) Indigenous R&D.

In particular it was noted that the Intelligence Community had not kept pacewith the changing nature of the threat and that, crucially, ‘current analysisoften fails to place foreign S&T and weapons developments in the context ofan adversary’s plans, strategy, policies and overall capabilities’.

Lynn, Connie. “Making the Most of MASINT and Advanced Geospatial Intelligence.” Master’s thesis, Marine Corps University, 2012.

ABSTRACTMaking the most of measurement and signatures intelligence (MASINT) requires a deeper, technical level of understanding and the creative insight to match MASINT applications to whole of government, mid to long-term problem sets that require the forensic-level data and rigorous analysis that MASINT is designed to provide. To explore these issues, a short background in the evolution of MASINT as a discipline will be presented. It will be followed by a description of each of the two problem areas mentioned above. In order to illustrate the issues, three examples of MASINT advanced geospatial intelligence (AGI) concepts will be discussed in terms of the basic phenomenology, requirements for processing, production of intelligence and recent success stories. The examples will be followed by a description of the efforts made to adapt MASINT technologies for faster response times. Finally, the conclusion will offer suggestions on reducing the knowledge gap and mitigating the time intensive nature of MASINT by encouraging greater creativity in applying MASINT principles to problem sets in all sectors of government

As a result of the complex, diverse nature of MASINT, two fundamental problem areas emerge. The first problem is the relatively lengthy time required to produce relevant intelligence from MASINT. The second problem is that a knowledge gap still exists between the scientists who are well versed in the underlying principles of MASINT technologies and the operators and analysts who have intelligence questions that MASINT sources may be able to help answer.

In order to use MASINT to its fullest potential, the greater community of end users should be better informed on existing capabilities and the science behind them. Further, academia-based MASINT scientists should continue to be integrated into government intelligence programs in a way that minimizes loss of proficiency in their primary specialty.

Mugavero, Roberto, Federico Belloni and Valentina Sabato, “Challenges of Multi-Source Data and Information New Era.” Journal of Information Privacy and Security 11 (2015): 230-242

As a consequence of the advancement of modern global dynamics, the international debate concern-ing intelligence strategies is pointing to an investigative tools revolution. To keep up with the paceof advancement, these tools have to be able to collect and convert data taking advantage of the entirespectrum of technological expertise and methodological progress. In this view, a multi-source intelli-gence technique appears the leading approach to effectively respond to the needs of the community.Actually, a steady interaction among information acquiredfrom the principal disciplines of IMINT,MASINT, SIGINT, GEOINT, HUMINT and OSINT should supply an undeniable value added inorder to offer effective products, which are intuitive, clear, and timely. The principal purpose is toanalyze and display how the intelligence community’s interactive network operates according to bothstandard and intelligence, security and defense requests

The first international academic publication concerning intelligence was entitled “StrategicIntelligence for American World Policy” by Sherman Kent. The author, through his work,exceeded the previous vision of intelligence, which consideredintelligenceandespionageassynonyms, defining three “new” concepts (Davis,2002a). First, the concept of intelligence wascompared to knowledge: that kind of awareness essential to policy makers and the military aswell as people involved in obtaining intelligence to predict emerging scenarios. Second, the useof the word intelligence describes the Organization that creates relevant products. Finally, intelli-gence describes a process to collect significant data and itssubsequent analysis in order to makethe information suitable to protect the National Welfare (Van Alstyne,1949)