Así fue como redescubri la formula de sumatoria con patrones {Esp/Eng}

[ESP]

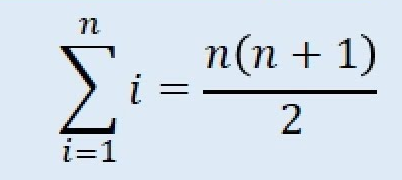

Recuerdo estar en una clase de álgebra lineal cuando me presentaron por primera vez la fórmula de sumatoria. Se que más de una persona que está leyendo esto la vió por lo menos una vez en la vida:

Creo que a todos nos contaron la historia de cuando Gauss era tan solo un niño y su profesor castigó a su clase, pidiendoles que sumen los numeros del 1 al 100, para lo cuás, Gauss creó dicha fórmula para ahorrar tiempo.

Recuerdo meses despues de esta clase, estar en mi casa en el baño y pensando... "tiene que haber una formula para por ejemplo calcular de los primeros 100/200/300/400... que sea de otra forma, tal vez, más simplificada y que sabia que la iba a descubrir en base a los resultados obtenidos, sabia que podia encontrar un patrón. Siempre siento que cuanto más grandes son las cifras, es más sencillo encontrar el patrón.

Fue así como fui a mi habitación, borré lo que tenia escrito en la pizarra y empecé a analizar las sumatorias de los primeros 100 numeros. Los resultados eran los siguientes:

Sumatorias:

Al 100: 5.050

Al 200: 20.100

Al 300: 45.150

Al 400: 80.200

Al 500: 125.250

Lo primero que intenté fue encontrar un patrón entre la distribución. Sentia que podria encontrar un patrón evidente entre la diferencia de las sumatorias, pero no lo logré, al menos no una que fuera sostenida.

Luego de intentar varias cosas que no funcionaron, me centré en los numeros y lo primero que me llamó la atención fue que, si tomabamos los ultimos numeros de los valores, siempre terminaba en "50" o "00" y empecé a prestarle más atención a esto.

Podemos notar que los ultimos digitos siempre se van incrementando de 50 en 50. Por ejemplo:

En los primeros 100 la sumatoria es 5."050", para los 200 es 20."100", para los 300 es 45."150", y asi sucesivamente se va repitiendo con el resto.

De esta forma fuí separando los valores entre las centenas y los miles.

Ya habia encontrado un primer patrón que era que a medida que pasabamos de 100 a 100, las centenas siempre se incrementaban de a 50. Ahora faltaba la parte de los miles.

Si obviamos las centenas, encontramos la siguiente secuencia:

100 -> 5

200 -> 20

300 -> 45

400 -> 80

500 -> 125

Lo primero que podemos notar de forma evidente, es que son todos múltiplos de "5", entonces lo que hacemos es descomponer el numero, nos queda lo siguiente.

100 -> 1.5 = 5

200 -> 4.5 = 20

300 -> 9.5 = 45

400 -> 16.5 = 80

500 -> 25.5 = 125

Haciendo esto, podemos encontrar una nueva secuencia: 1, 4, 9, 16, 25...

Si prestamos atención, podemos ver que es una sucesion conocida, dicha sucesion es la de los cuadrados de los números naturales.

1² = 1

2² = 4

3² = 9

4² = 16

5² = 25

Otra particularidad era que, para los primeros 100 numeros, correspondia el 1², para los 200 el 2², para los 300 el 3². Entonces podiamos usar el numero como

"(x/100)²".

Entonces me puse a generar una fórmula para probar si esto se cumplica para cualquier valor que pruebe.

Ya sabiamos que los resultados iban subiendo de 50 en 50, y que la serie se incrementaba de 100 en 100, entonces quedaria en "(x/100).50".

Una vez que encontramos esto, quedaba hacer la formula general.

"(x/100)²" faltaba agregarle los miles y multiplicar por 5, recuerden que habiamos dividido por 5 todos los numeros de esa sucesion, entonces ese fragmento nos quedaria en = "(x/100)² . 5000" simplificando nos queda "(x²/2)"

La segunda parte quedaba como tal. "(x/100).50" si simplificamos nos queda "(x/2)"

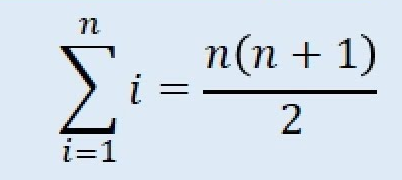

Si sumamos ambos terminos nos quedaria "(x²/2) + (x/2)" -> "(x²+x)/2" -> "[x.(x+1)] /2"

Mi sorpresa fue enorme al darme cuenta que la fórmula a la que habia llegado, era exactamente igual a la que habia visto en esa clase, meses atrás...

[ENG]

I remember being in a linear algebra class when I was first introduced to the summation formula. I know that more than one person reading this has seen it at least once in their life:

I think we have all been told the story of when Gauss was just a child and his teacher punished his class by asking them to add the numbers from 1 to 100, for which Gauss created this formula to save time.

I remember months after this class, being at home in the bathroom and thinking... "there has to be a formula to, for example, calculate the first 100/200/300/400... let it be another way, maybe , more simplified and I knew that I was going to discover it based on the results obtained, I knew that I could find a pattern. I always feel that the larger the figures, the easier it is to find the pattern.

That's how I went to my room, erased what I had written on the blackboard and began to analyze the sums of the first 100 numbers. The results were the following:

Summations:

to 100: 5.050

to 200: 20.100

to 300: 45.150

to 400: 80.200

to 500: 125.250

The first thing I tried was to find a pattern among the distribution. I felt like I could find an obvious pattern between the difference in the sums, but I couldn't, at least not one that was sustained.

After trying several things that didn't work, I focused on the numbers and the first thing that caught my attention was that, if we took the last numbers of the values, it always ended in "50" or "00" and I started to pay more attention to it. to this.

We can notice that the last digits always increase by 50 by 50. For example:

In the first 100 the sum is 5.050, for the 200 it is 20.100, for the 300 it is 45.150, and so on it is repeated with the rest.

In this way I separated the values between hundreds and thousands.

I had already found a first pattern which was that as we went from 100 to 100, the hundreds always increased by 50. Now the thousands part was missing.

If we ignore the hundreds, we find the following sequence:

100 -> 5

200 -> 20

300 -> 45

400 -> 80

500 -> 125

The first thing we can notice clearly is that they are all multiples of "5", so what we do is decompose the number, we are left with the following.

100 -> 1.5 = 5

200 -> 4.5 = 20

300 -> 9.5 = 45

400 -> 16.5 = 80

500 -> 25.5 = 125

By doing this, we can find a new sequence: 1, 4, 9, 16, 25...

If we pay attention, we can see that it is a known sequence, said sequence is that of the squares of the natural numbers.

1² = 1

2² = 4

3² = 9

4² = 16

5² = 25

Another peculiarity was that, for the first 100 numbers, 1² corresponded, for the 200 the 2², for the 300 the 3². So we could use the number as

"(x/100)²".

So I set about generating a formula to test if this holds for any value I test.

We already knew that the results were increasing by 50 by 50, and that the series was increasing by 100 by 100, so it would remain at "(x/100).50".

Once we found this, it was left to make the general formula.

"(x/100)²" we needed to add the thousands and multiply by 5, remember that we had divided all the numbers of that sequence by 5, so that fragment would be = "(x/100)². 5000" simplifying we are left "(x²/2)"

The second part remained as such. "(x/100).50" if we simplify we get "(x/2)"

If we add both terms we would have "(x²/2) + (x/2)" -> "(x²+x)/2" -> "[x.(x+1)] /2"

My surprise was enormous when I realized that the formula I had arrived at was exactly the same as the one I had seen in that class, months ago...

Una mención especial a @ydavgonzalez , ver tus post sobre matematicás me impulsó a mostrar esto por primera vez... Lo tengo guardado hace más de 5 años. Espero que la comunidad de matemática pueda crecer

You can check out this post and your own profile on the map. Be part of the Worldmappin Community and join our Discord Channel to get in touch with other travelers, ask questions or just be updated on our latest features.