The Shifting Paradigm of Disease Looking at the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

In the face of pandemics, both in our modern era and the world of the past, it's fascinating to explore how people in bygone days coped with health crises that we continue to confront today. These historical perspectives provide insight into the evolution of medical knowledge and innovation.

By 1918, scientist already understood what vaccines were as there were vaccines for small pox, and the plaque at that time but then, there was no vaccine for influenza at that time. At the end of the 19th century, the acceptance of germ theory, the use of microscope, and proper hygiene was a thing in the world of medicine. With germ theory, it was a consensus that specific germs caused specific diseases, as people now agreed that it wasn't the wrath of the gods, or poisoned air that caused diseases, rather it was caused by specific viruses, and bacteria and with Koch's postulate, it was possible to identify a particular germ that caused a disease.

In 1889, the world was dealing with the Influenza pandemic that killed about 1 million people and to find out what was causing the bacteria, Scientists decided to use the Koch's postulate. Scientists such as Richard Pfeiffer published a paper in 1892 where he claimed he had found the culprit of the influenza. When he checked samples of people who had the influenza, he saw a rod-shaped bacteria which he named Baccillus Influenzae. In his paper, he said that the bacteria was difficult to culture but he was able to do so. While he was able to meet the Koch's postulate that mentioned isolating the bacteria, and regrowing the bacteria, he was not able to cause disease when transferred into healthy person/animal.

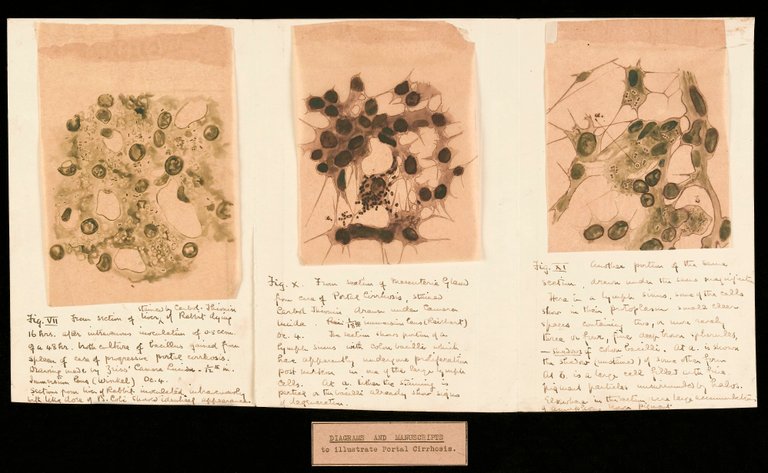

Over the years, scientists revisited Pfeiffer's findings and obtained mixed results. While some discovered the Bacillus influenzae in people with influenza, others found it in healthy individuals, and some even detected the bacteria in diseases unrelated to the flu. Additionally, staining the bacteria to visualize it under the microscope posed challenges, as it could be mistaken for diplococci.

In 1912, William Osler attributed the flu to Bacillus influenzae but offered no further insights or research on the subject. It was considered the leading theory regarding the flu's causative agent during the 1918 pandemic. However, a breakthrough occurred in 1917 when an outbreak of measles affected US soldiers. Autopsies revealed extensive bacterial infections in the soldiers' lungs, leading to pus accumulation both within and outside the cavities, causing damage to bronchioles and sepsis. This dual infection demonstrated that the primary illness, measles, was followed by a secondary bacterial infection, leading to pneumonia.

In April 1918, a public health report was published in response to an outbreak of severe influenza cases, resulting in three fatalities among 18 reported cases. Autopsies indicated that these patients exhibited lung conditions similar to the pus-filled lungs observed in soldiers with measles. Yet, the scientists couldn't consistently culture Bacillus influenzae from all the patients, raising doubts about its role in clinical influenza cases.

At this time scientist knew that while they could see bacteria with the microscope, there were germs smaller than bacteria. To get these germs, they would pass a heap of bacteria through Pasteur's chamberland to filter then culture whatever passed through the filter. This was known as Filter passable germs which we now know as Viruses.

Scientists Peter Olitsky, and Fredrick Gates in their paper "Experimental Studies Of The Nasopharyngeal Secreations from Influenza Patients" explained how they took snuts from influenza patients, filtered the bacteria before culturing to see if they would find filter passable germs which they did. They then transferred the filter passable germs into rabbits, and it made them sick. This was a prove that influenza wasn't caused by a bacteria but a filter passable germ. The idea that the flu caused the virus wasn't completely agreed on at the time.

If they were to provide a vaccine for the flu, then they needed to understand what flu they were fighting against but Dr Park was going to create a vaccine to fight against the bacteria Baccillus influenzae. He heated the bacteria and gave them to volunteers and he was hopeful that he would be able to vaccinate people against the bacteria but then, the bacteria was not the cause of the flu. A lot of other universities and people started to make vaccine for this incorrect causative agent with the hope of building a stronger immune system to ward against it.

While these vaccines failed, the worst of the 1918 pandemic eventually subsided. Decades later, in 1918 and 1929, farmers in Iowa reported a disease in pigs resembling the flu. When they cultured samples from the pigs, they found Pfeiffer's bacillus. Yet, when this bacteria was injected into healthy pigs, it didn't induce illness. However, the filter-passable germ from the same cultures did cause the disease in pigs.

Furthermore, mixing this filter-passable germ with bacteria resulted in a more severe illness, shedding light on the fact that the germ (virus) was the primary infection, while the bacteria constituted a secondary infection. These findings were published in "Swine Influenza; Filtration Experiments and Etiology," underscoring that scientists, while initially working with bacteria to combat influenza, had been dealing with a virus all along.

Exploring the historical perspective of how scientists navigated the 1918 influenza pandemic offers valuable insights into the development of medical knowledge and research methods. While they were unable to find the virus easily, it has helped us in identifying flu and flu-like viral strain such as the Covid-19 virus.

Read More

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8813723/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22148/

https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/news/epidemic-endemic-pandemic-what-are-differences

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2118275/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862332/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26485863

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2391305/

https://www.history.com/news/spanish-flu-second-wave-resurgence

https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/1918-flu-pandemic

https://rupress.org/jem/article-pdf/34/1/1/1175948/1.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2728380/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6617519/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2599911/

https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/fromdnatobeer/exhibition-interactive/pasteur-chamberland-filter/pasteur-chamberland-filter-alt.html

https://www.paho.org/en/who-we-are/history-paho/purple-death-great-flu-1918

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7931561/

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7077202/

https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/a-brief-history-of-vaccination

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3310093/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24631908

https://veterinaryresearch.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1297-9716-43-24

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6269246/

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

Thanks for including @stemsocial as a beneficiary, which gives you stronger support.