Condensation

In Evaporating Oceans, the third section of Chapter IX of Earth in Upheaval, Immanuel Velikovsky argued that the massive ice caps which covered the Earth’s polar regions during glacial periods would never have formed if the planet’s global mean surface temperature had simply dropped by several degrees. Those ice caps were made of compacted snow, and in order to produce all that snow the oceans must first be exposed to a tremendous amount of heat. The evaporation of water is an essential prerequisite to the formation of extensive polar caps.

After evaporation, however, comes condensation:

In the preceding section it was made clear that, for the ice cover of the glacial epoch to be formed, evaporation of the oceans on a large scale must have occurred. But evaporation of the oceans would not be enough; rapid and powerful condensation of the vapors must have followed. “We need a condenser so powerful that this vapour, instead of falling in liquid showers to the earth, shall be so far reduced in temperature as to descend as snow.” ―Velikovsky 122–123

The quotation is taken from John Tyndall’s Heat Considered as a Mode of Motion, one of the principal sources Velikovsky drew on in the previous section.

Velikovsky contends that only a rapid and catastrophic sequence of evaporation followed by condensation can account for the glacial ice caps:

An unusual sequence of events was necessary: the oceans must have steamed and the vaporized water must have fallen as snow in latitudes of temperate climates. This sequence of heat and cold must have taken place in quick succession.

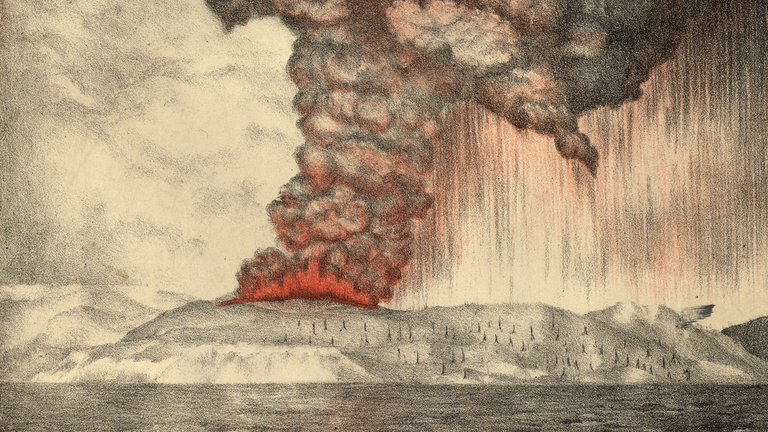

A precipitate drop in temperature and a rapid condensation of vapors could have followed from the screening effect of clouds of dust. Dust of either volcanic or meteoric origin, by enveloping the earth, could have impaired the solar light and warmth reaching the lower atmosphere. The dust particles ejected by erupting volcanoes have been observed to float in the sky around the globe for many months. So, after the eruption of Krakatoa in Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra in 1883, dust particles suspended in the atmosphere continued for over a year to act as a screen around the world that caused the sunsets to be unusually colorful. Dust from many volcanoes could build a screen that would obstruct the solar light. Actually the screening of the earth by clouds of dust of volcanic origin was one of the theories concerning the origin of ice in the glacial epochs; however, like heat alone, cold alone would not have sufficed to produce the continental ice covers. ―Velikovsky 123

The evidence presented by the cataclysmic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 is taken from a report on the eruption prepared by a committee of the Royal Society. The thirteen-member committee included some notable scientists from several different disciplines:

Archibald Geikie, the Scottish geologist.

Norman Lockyer, the English astronomer.

George Stokes, the Irish physicist.

The committee was chaired by G J Symons, a British meteorologist, who edited the final report. Velikovsky cites pages 40 ff to the effect that the colourful sunsets witnessed across the globe in the wake of the eruption were probably caused by the volcanic dust ejected into the Earth’s stratosphere:

What was the percentage of ultra-microscopical particles which remained in the atmosphere after the larger ones had fallen it is impossible to determine, but it was not improbably very considerable. It is for physicists to determine whether such particles were capable of producing the wonderful optical phenomena which followed the eruption of Krakatoa, either acting by themselves, or performing the part of condensers of watery vapour, in the manner which Mr. Aitken has shown such particles to be capable of doing. ―Symons 41–42

There is nothing in the report to substantiate Velikovsky’s surmise that this dust could have screened the planet from the solar radiation, leading to a drop in the surface temperature, but this phenomenon is now well-established. 1816, the year following the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, came to be known as the Year Without a Summer. Global temperatures for that year were around 0.4–0.7 °C lower than average. The eruption of Krakatoa had at least as great an effect on the summer temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere, with drops of as much as 0.7 °C being recorded (Bradley 230). It is curious that this well-known effect is not detailed in the Royal Society’s report.

The hypothesis that the screening of the earth by clouds of dust caused of the ice ages was one of the theories Velikovsky briefly mentioned in the opening section of the previous chapter, though he did not invoke volcanism:

Of the atmospheric conditions that could effect a rise or drop in temperature, the varying quantity ... of dust particles was called on to explain the changes in temperature in the past ... If the earth were enveloped in clouds of dust that kept the rays of the sun from penetrating to the ground, there would be a fall in temperature. However, one would have to explain where such extensive and thick clouds of dust in the atmosphere could come from. ―Velikovsky 101

Although Velikovsky does not cite his source, I have identified it as Arthur Philemon Coleman’s Ice Ages Recent and Ancient:

The screening effect of volcanic dust in the air also has been considered important in lowering temperatures ...

Humphreys has recently worked out in some detail a theory of glaciation as caused by the screening action of volcanic dust in the air. In the case of the explosions of Krakatoa, Pelee and Katmai the finest particles of dust were flung high into the air and reached the stratosphere, or isothermal region, perhaps even 25 to 50 miles above the surface, where there is no washing effect of snow or rain, and where they required from one to three years to return to the earth by the action of gravity. The finest dust particles “shut out solar radiation manifold more effectively than they hold back terrestrial radiation.” The effect of the amount of dust sent out by Katmai, if long continued, would be to lower the temperature by several degrees Centigrade. “This small amount of solid material distributed once a year, or even once in two years, through the upper atmosphere, would be more than sufficient to maintain continuously, or nearly so, the low temperature requisite to the production of an ice age. . . . This quantity of dust yearly, during a period of 100,000 years, would produce a layer over the earth only about half a millimeter, or one-fiftieth of an inch thick, and therefore one could hardly expect to find any marked accumulation of it, even if it had once filled the atmosphere for much longer periods.”

He believes that within the last 160 years such violent volcanic explosions have lowered the average temperature as much as half a degree Centigrade, and that if the eruptions had been three or four times as numerous the snowline would have been depressed 300 meters (about 1,000 ft.), thus beginning a moderate ice age. ―Coleman 268 ... 270

Coleman has his doubts:

Though the theory is in some ways an attractive one, it seems to the present writer that most geologists will hesitate to assume such a steady and long-continued series of explosive eruptions as would be required for the hundreds of thousands of years of glaciation in the late Palaeozoic and Pleistocene ice ages. Nevertheless vulcanism supplies a subordinate cause of refrigeration which might for a few years reinforce some more general cause in initiating a great snow sheet ; which would be more or less self-perpetuating in later times. ―Coleman 271

Coleman does not consider Velikovsky’s objection that cold alone is insufficient to cause an ice age. This seems to be a blind spot with many Uniformitarians.

Pluvials

In Chapter VI―in the section entitled A Continent Torn Apart―Velikovsky cited the British geologist John Walter Gregory, who led an expedition to Mount Kenya, overlooking the Great Rift Valley, in the 1890s. Gregory pioneered the geological study of the Great Rift Valley―a name he coined. It was also during his time in Africa that he observed a relation between glacial periods in Europe and periods of increased precipitation in Africa, or pluvials:

Gregory long ago suggested that European glacial maxima corresponded with equatorial pluvial maxima, and Leakey has brought forward evidence for the same conclusion. ―Fleure 371

In The Rift Valleys and Geology of East Africa (1921) Gregory writes:

... the “pluvial period,” which was approximately synchronous with the glacial period of Europe. ―Gregory 341

In support of the correlation of pluvials and glacials Velikovsky also quotes the American geologist Richard Foster Flint and the British anthropologist Louis Leakey. He might have been more selective, however, in choosing an appropriate quotation from Flint’s Glacial Geology And The Pleistocene Epoch:

There remained in the Sahara and adjacent regions stream channels “not now occupied by water courses” that obviously carried great quantities of water. “It is believed probable that these streamways were trenched during a pluvial age or pluvial ages” (Flint) ... Shor Kul, a salt lake in Sinkiang, had its

level 350 feet [110 m] higher than it is today. Lake Bonneville, which occupied parts of Utah, Nevada, and Idaho, and collected pluvial water as well as melt water from the local glaciers in the mountains, stood “more than 1000 feet [300 m] above the present Great Salt Lake.” ―Velikovsky 123–124 : Flint 485 ... 472, 479

Earlier in the same work Flint had written the following, which may have made Velikovsky’s point more succinctly:

This discussion leads to the conclusion that the pluvial ages of expanded lakes were contemporaneous with the glacial ages―that the two reached their maxima at the same times. The evidence in support of this conclusion is both direct geologic evidence of the close association of expanded lakes and glaciers and indirect deductive evidence that the growth of the former ice sheets should have provided the atmospheric mechanism required to produce the pluvial phenomena. The case is not entirely closed, but the probability is of a high order. ―Flint 469

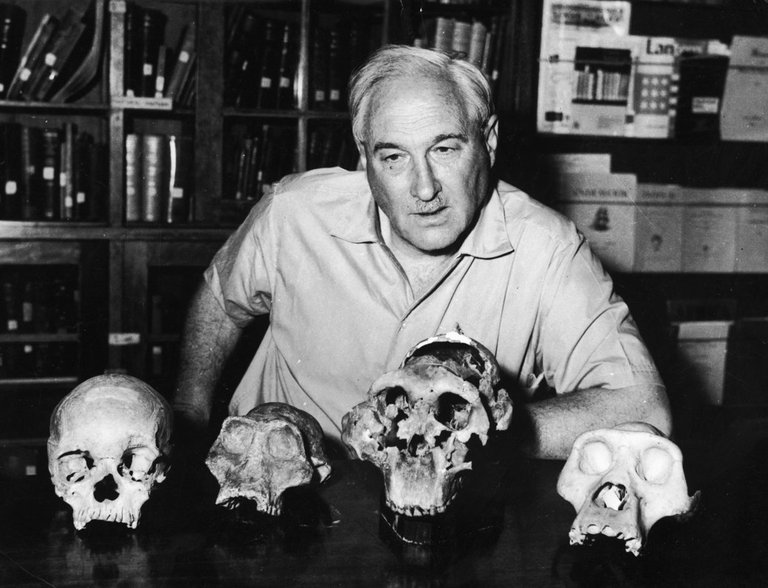

Louis Leakey is best known for his anthropological discoveries in the Rift Valley’s Olduvai Gorge. But Velikovsky cites a paper he presented at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society in 1934. The subject of his talk was the effect climate change had on the great lakes of East Africa during the Pleistocene and Holocene.

In the Pluvial, Lake Victoria in Africa stood over 300 feet [90 m] above its present level; since that time there was a complete reversal of the river system in the region. ―Velikovsky 124

Once again, Velikovsky has selected from Leakey’s paper what appear to be two random facts:

In addition to this great lake lying in the central region of East Africa where the eastern branch of the Great Rift Valley runs to-day you will notice that the area allotted to Lake Victoria is very much greater than at present. We have abundant evidence that the waters of the great lake stood some 300 feet above the present level, and that fact involves a much larger area of submergence ... Among other changes of physical geography which have taken place now in this region we must take into account the complete reversal of some of the river systems on the western side of Lake Victoria. ―Leakey 301 ...

I believe that Velikovsky included the detail about the reversal of the river systems simply because it sounded more catastrophist than gradualist. It is not really relevant to his main point: that during glacial periods global precipitation was considerably greater than it is today. This in turn supports Velikovsky’s contention that at the beginning of each glacial period something occurred that resulted in a dramatic increase in oceanic evaporation.

Velikovsky concludes this short section―it is less than two pages long―with a brief summary:

Although some geologists, on theoretical grounds, would prefer to think that a dry climate prevailed in the world when so much water was concentrated in the ice covers, field geology shows the opposite to have been the case: snow fell in huge masses, and rain cascaded from the sky at the very same time. ―Velikovsky 124

In the next section of Earth in Upheaval Velikovsky will present, as a working hypothesis, his explanation of the ice ages.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Raymond S Bradley, The Explosive Volcanic Eruption Signal in Northern Hemisphere Continental Temperature Records, Climatic Change, Volume 12, Issue 3, Pages 221–243, Springer Science+Business Media, Berlin (1988)

- Arthur Philemon Coleman, Ice Ages Recent and Ancient, The Macmillan Company, New York (1926)

H J Fleure (chairman), Discussion on The Relation between Past Pluvial and Glacial Periods, Report of the Ninety-Eighth Meeting, British Association for the Advancement of Science, London (1931) - Richard Foster Flint, Glacial Geology And The Pleistocene Epoch, John Wiley And Sons, Inc, New York (1955)

- John Walter Gregory, The Rift Valleys and Geology of East Africa, Seeley, Service & Co, Limited, London (1921)

- Louis S B Leakey, Changes in the Physical Geography of East Africa in Human Times, The Geographical Journal, Volume 84, Number 4, Pages 296–305, The Royal Geographical Society, London (1934).

- George James Symons (editor), The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of The Krakatoa Committee of The Royal Society, (1888)

- John Tyndall, Heat Considered as a Mode of Motion, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, London (1863)

- Immanuel Velikovsky, Earth in Upheaval, Pocket Books, Simon & Schuster, New York (1955, 1977)

Image Credits

- Glacial Snowstorm: © Ivan Kmit (photographer), Fair Use

- John Tyndall: Lock & Whitfield (photographers), Wellcome Images, Public Domain

- The Eruption of Krakatoa in 1883: Parker & Coward (lithographers), West Newman & Co, George James Symons (editor), The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of The Krakatoa Committee of The Royal Society, Plate 1 (1888), Public Domain

- Twilight & Afterglow Effects in London (November 1883): W Ashcroft (painter), Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company (chromo-lithographers), George James Symons (editor), The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of The Krakatoa Committee of The Royal Society, Frontispiece (1888), Public Domain

- Arthur Philemon Coleman: J R L Forster (artist), Public Domain

- John Walter Gregory: Anonymous Photograph (1932?), Public Domain

- Richard Foster Flint: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- Louis Leakey: Anonymous Photograph, Hulton Archive, Fair Use

Thanks for your contribution to the STEMsocial community. Feel free to join us on discord to get to know the rest of us!

Please consider delegating to the @stemsocial account (85% of the curation rewards are returned).

You may also include @stemsocial as a beneficiary of the rewards of this post to get a stronger support.