| a także o tym, jak taki tunel czasoprzestrzenny wykorzystać jako wehikuł czasu (w końcu czas i przestrzeń są nierozdzielne...). Takie koncepcje miało już co najmniej kilku uczonych – Van Stockum, Kurt Gödel, Kip Thorne czy Richard Gott – a my się z tymi koncepcjami zapoznajemy. I przekonujemy się, że wbrew zdrowemu rozsądkowi może istnieć coś takiego, jak ujemna energia. |

and how such a spacetime tunnel could be used as a time machine (after all, time and space are inseparable...). At least a few scientists - Van Stockum, Kurt Gödel, Kip Thorne or Richard Gott - have already had such ideas, and we become familiar with them. And we discover that, contrary to common sense, such a thing as negative energy can exist. |

| Rozdział szósty wynosi abstrakcję na jeszcze wyższy poziom – tym razem tematem przewodnim są równoległe wszechświaty kwantowe. I to już się naprawdę ciężko streszcza i omawia tak, żeby przy okazji nie umknął sens... W każdym razie pełno tu pojęć takich jak funkcja falowa, determinizm, nieoznaczoność, dekoherencja, komputery kwantowe czy teleportacja. I rozważań filozoficznych w rodzaju: czy drzewo w lesie się przewróciło, jeśli nikt go nie widzi? A także, czy kot w zamkniętym pudełku jest żywy, czy martwy? Jak się przekonamy, pozornie oderwane od życia rozważania doprowadziły, między innymi, do Hiroshimy i Nagasaki. Mamy też kolejne paralele z utworami Lema – tym razem teoria Johna Wheelera („Z bitu byt”) jest zastanawiająco zbieżna z teorią profesora Dońdy o równoważności informacji z materią i energią. |

The sixth chapter takes the abstraction to an even higher level - this time the main topic is parallel quantum universes. And this is already really hard to summarise and discuss in such a way that the meaning is not lost in the process... In any case, it is full of concepts such as the wave function, determinism, indeterminism, decoherence, quantum computers or teleportation. And philosophical considerations like: has a tree in the forest fallen over if no one can see it? And also, is a cat in a closed box alive or dead? As we shall see, deliberations seemingly detached from life led, among other things, to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We also have further parallels with Lem's works - this time, John Wheeler's theory ('It from bit') is surprisingly congruent with Professor Dońda's theory of the equivalence of information with matter and energy. |

| W rozdziale siódmym, poświęconym tzw. „M-teorii”, musimy swoją wyobraźnię wprowadzić na jeszcze wyższe obroty. Zaczyna się „w miarę” łagodnie, wprowadzeniem do Krainy Płaszczaków, wymyślonej przez Edwina Abbotta. Ten wyłącznie dwuwymiarowy świat jest zamieszkiwany przez płaskie istoty – i mamy możliwość się przekonać, jak istoty trójwymiarowe, takie jak ludzie, w takim świecie stają się wszechmocne. Następnym krokiem jest uświadomienie sobie idei, że takie same możliwości miałyby w naszym świecie istoty czterowymiarowe, których nigdy nie będziemy w stanie sobie w pełni wyobrazić. A wszystko to po to, żeby zaraz potem skoczyć na głębię teorii strun, które, w zasadzie, są potencjalnie w stanie zunifikować fizykę klasyczną i kwantową i stać się teorią wszystkiego. Jest tylko taki malutki problemik – żeby mogły zadziałać, a zwłaszcza rozwiązać problem kwantowej grawitacji, muszą funkcjonować w dziesięciu wymiarach. A to już są w stanie sobie w miarę wyobrazić tylko matematycy. W każdym razie – struny rozmiaru długości Plancka, sześć wymiarów zwinięte w kulkę podobnej średnicy i tak dalej. Nic, co bylibyśmy w stanie w jakikolwiek zbadać doświadczalnie. I tak sobie przechodzimy przez historię teorii strun, od ich powstania, przez rozkwit, aż do zniechęcenia fizyków i ponownego rozkwitu, gdy się okazało, że dziesięciowymiarowe struny bardzo dobrze się uzupełniają matematycznie z jedenastowymiarowymi membranami (dlatego M-teoria). Konsekwencją prawdziwości takiej teorii może być wytłumaczenie problemu ciemnej materii jako wpływu równoległego wszechświata, podobnego do naszego, tylko istniejącego w innym wymiarze. Uzasadnionymi wnioskami mogą być też to, że nasz Wszechświat, w którym żyjemy, jest hologramem, a może wręcz nawet programem komputerowym – i że takich wszechświatów jest nieskończenie dużo. |

In chapter seven, dedicated to so-called 'M-theory', we need to bring our imagination into even higher gear. It begins 'fairly' gently, with an introduction to the Flatland, invented by Edwin Abbott. This only two-dimensional world is inhabited by flat creatures - and we are given the opportunity to see how three-dimensional beings, such as humans, become omnipotent in such a world. The next step is to realise the idea that four-dimensional beings, which we can never fully imagine, would have the same capabilities in our world. And all this to immediately jump to the depths of the string theories, which, in principle, are potentially able to unify classical and quantum physics and become the theory of everything. There's just a tiny problem - in order for them to work, and especially to solve the problem of quantum gravity, they have to operate in ten dimensions. And this is something only mathematicians can reasonably imagine. Anyway - strings the size of a Planck length, six dimensions rolled into a ball of similar diameter and so on. Nothing that we would be able to investigate experimentally in any way. And so we go through the history of string theory, from its inception, through its heyday, up to the discouragement of physicists and then its re-emergence when it turned out that ten-dimensional strings were mathematically very complementary to eleven-dimensional membranes (hence M-theory). A consequence of such a theory being true could be to explain the dark matter problem as the influence of a parallel universe, similar to our own, but existing in a different dimension. Legitimate conclusions might also be that our Universe, in which we live, is a hologram, or perhaps even a computer programme - and that there are infinitely many such universes. |

| Jeśli po powyższym jeszcze nie macie dość, to mam dobrą wiadomość – rozdział ósmy jest już łatwiejszy do przyswojenia. Są w nim przedstawione rozważania na temat tego, czy Wszechświat może być celowym projektem. I rzeczywiście, pozornie takich przesłanek może być sporo – co doprowadziło jednych do wiary w bóstwo, które sprawiło, że prawa natury są akurat idealnie takie, żeby mogło powstać życie i ludzkość, innych – do przyjęcia założenia, że był to po prostu szczęśliwy zbieg okoliczności, że taki zestaw praw się trafił, a jeszcze innych – do obojętnego wzruszenia ramionami i stwierdzenia, że skoro w Multiwszechświecie jest nieskończenie dużo wszechświatów, to w tejże nieskończoności po prostu musiał się trafić przynajmniej jeden, w którym parametry się dobrały idealnie. I cały rozdział opowiada o tym, jakie to są parametry, jakie mają wartości i co z tego wynika. |

If you still haven't had enough after the above, there is good news - chapter eight is already easier to digest. It presents considerations about whether the Universe might be a deliberate design. And indeed, there may seem to be many such premises - leading some to believe in some deity who made the laws of nature just right for life and humanity to arise, others - to the assumption that it was just a lucky coincidence that such a set of laws came into existence, and yet others - to the indifferent shoulder shrug and the statement that since there are infinitely many universes in the Multiverse, then in this infinity there simply had to be at least one in which the parameters were perfectly matched. And the whole chapter is about what these parameters are, what values they have and what follows from this. |

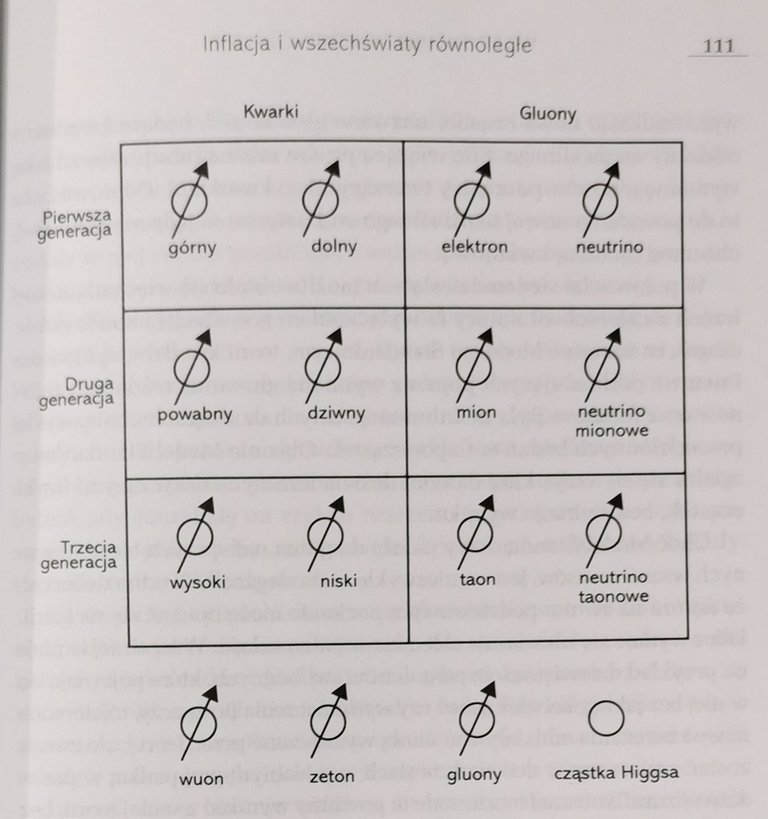

| Z kolei w rozdziale dziewiątym autor próbuje nam przedstawić sposoby, które potencjalnie mogą nam umożliwić potwierdzenie M-teorii. Przy czym oczywistym jest, że nie wchodzi w grę potwierdzenie bezpośrednie – wymagałoby to stworzenia warunków takich, jakie panowały tuż po Wielkim Wybuchu. A tego ludzkość by prawdopodobnie nie przetrwała – zresztą, nawet gdyby udało się je wytworzyć w jakimś skutecznie izolowanym układzie, wymagałoby to takiej energii, jakiej ludzkość nie będzie w stanie wytworzyć jeszcze przez tysiące lat, jeśli nie dłużej. Być może nawet całej energii wszechświata. Cóż więc pozostaje? Teorie fizyczne często są potwierdzane metodami pośrednimi, i tak też potencjalnie może być z M-teorią. Z pomocą mogą przyjść, na przykład, niezwykle czułe wykrywacze fal grawitacyjnych (np. projekt LISA, mający na chwilę obecną opóźnienie 27 lat względem momentu wydania książki), detektory ciemnej materii, czy Wielki Zderzacz Hadronów (od czasu ukazania się książki udało się już chociażby wykryć bozon Higgsa). A może do udowodnienia M-teorii wystarczy jedynie matematyka? |

In chapter nine, on the other hand, the author tries to show us ways that could potentially enable us to confirm the M-theory. While it is obvious that direct confirmation is out of the question - this would require the creation of conditions like those that prevailed just after the Big Bang. And this would probably not be survivable by humanity - moreover, even if it could be produced in some effectively isolated system, it would require an energy that humanity would not be able to produce for thousands of years yet, if not longer. Perhaps even the energy of the entire universe. So what is left? Physical theories are often confirmed in indirect ways, and so it could potentially be with M-theory. Help may come, for example, from extremely sensitive gravitational wave detectors (e.g. the LISA project, currently with a delay of 27 years from the time of the book's publication), dark matter detectors or the Large Hadron Collider (since the book's publication, for example, the Higgs boson has already been detected). Or maybe mere mathematics is enough to prove M-theory? |

| Rozdział dziesiąty jest poświęcony końcowi naszego Wszechświata – poznajemy w nim poszczególne etapy historii Wszechświata, od Wielkiego Wybuchu i inflacji, przez erę gwiazdową, w której znajdujemy się obecnie, erę degeneracji, gdy już wszystkie gwiazdy się wypalą i zgasną, erę czarnych dziur i ostateczną erę ciemności, gdy prawdopodobnie nie będzie już nic poza nielicznymi elektronami, neutrinami czy fotonami. Przy czym jest to czyste teoretyzowanie – obecny wiek Wszechświata wyraża (z grubsza) jedynka i dziesięć zer, zaś era ciemności nastąpi, gdy tych zer będzie sto siedemnaście. A ta liczba odpowiada z grubsza liczbie atomów zebranych z septyliona wszechświatów takich, jak nasz. Co tu dużo mówić – nie dożyjemy tego my, nasze dzieci, wnuki, prawnuki, a w oczywisty sposób i ludzkość jako taka, w takiej postaci, jaką znamy. |

The tenth chapter is devoted to the end of our Universe - we learn about the different stages in the history of the Universe, from the Big Bang and inflation, through the stelliferous era in which we are now, the degenerate era, when all stars will have burned out and died, the black hole era and the final dark era, when there will probably be nothing left but a few electrons, neutrinos or photons. This is pure theorising - the present age of the Universe is expressed (roughly) by one and ten zeros, while the age of darkness will occur when these zeros are one hundred and seventeen. And this number roughly corresponds to the number of atoms collected from a septillion universes like ours. Needless to say, we, our children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and, of course, humanity as we know it, will not live long enough to see it. |

| Autor jednak rozważa, czy inteligencja – w jakiejkolwiek innej postaci – byłaby w stanie przetrwać śmierć Wszechświata (czy to w Wielkim Kolapsie, czy też w Wielkim Chłodzie) – i o tym jest rozdział jedenasty. Zapoznajemy się z klasyfikacją rozwoju cywilizacji według kryteriów Kardaszowa oraz kryteriów Sagana. Następnie zaś z sugestiami autora, co taka nieskończenie potężna cywilizacja mogłaby wymyślić, żeby się uratować: uciec przez czarną dziurę, stworzyć wszechświat potomny, do którego można by uciec, wytworzyć tunel czasoprzestrzenny, w najgorszym razie poczekać na przejście kwantowe, pomimo wszelkich trudności związanych z jego wykryciem, albo, gdy i to zawiedzie, zamiast samemu uciekać do innego wszechświata – przesłać tam jedynie informację, pozwalającą na odtworzenie tejże cywilizacji. |

However, the author considers whether intelligence - in any other form - would be able to survive the death of the Universe (whether in the Big Crunch or the Big Chill) - and this is what Chapter Eleven is about. We are introduced to the classification of the development of civilisations according to the Kardashev criteria and the Sagan criteria. Then, in turn, with the author's suggestions as to what such an infinitely powerful civilisation could do to save itself: escape through a black hole, create a baby universe to which it could escape, create a spacetime wormhole, in the worst case, wait for a quantum transition, despite all the difficulties involved in detecting it, or, when this too fails, instead of escaping to another universe on its own, just send information there, allowing that civilisation to be recreated. |

| Rozdział dwunasty to już czysta filozofia – rozważania na temat sensu Wszechświata i samej ludzkości w ujęciu historycznym, od, powiedzmy, Kopernika po współczesność. I o tym, czy jest w tym wszystkim gdzieś miejsce dla Boga, a jeśli tak, to jakie. Autor jest tu zdania, że obecne pokolenie jest najważniejszym w dotychczasowej historii ludzkości, bo jako pierwsze ma zarówno możliwość zapewnienia dalszego rozwoju cywilizacji, jak też jej całkowitego zniszczenia. I tym optymistycznym wnioskiem kończy się główna część książki. Dalej jest już tylko... |

The twelfth chapter is pure philosophy - reflections on the meaning of the Universe and humanity itself in historical terms, from, say, Copernicus to the present day. And about whether there is a place for God in all this, and if so, what place. Here, the author is of the opinion that the present generation is the most important in the history of mankind to date, because it is the first one to have the ability both to ensure the further development of civilisation and to destroy it completely. And with this optimistic conclusion, the main part of the book ends. What follows is just ... |

| Słownik. Bo fizyka kwantowa i kosmologia są jednak naukami zaawansowanymi i przepełnionymi różnego rodzaju terminologią. A choć autor raczej stara się je objaśniać na bieżąco w tekście, to jednak czasami trzeba sobie coś przypomnieć i przekopywanie się w tym celu przez setki poprzednich stron niekoniecznie jest dobrym pomysłem, nawet jeśli mamy indeks, który to ułatwia. Więc dostajemy 150 zwięzłych haseł odświeżających naszą pamięć – od stosunkowo prostych („potęgi dziesięciu”) po bardzo specjalistyczne („rozmaitość Calabiego-Yau” czy inna „przestrzeń jednospójna”). A szczególnie zainteresowani i ogarniający temat – także całkiem obszerną literaturę uzupełniającą. |

Glossary. Because quantum physics and cosmology, after all, are advanced sciences and full of all sorts of terminology. And although the author tends to explain them on the fly in the text, sometimes you need to recall something and digging through hundreds of previous pages for this purpose is not necessarily a good idea, even if we have an index to facilitate this. So we get 150 concise entries to refresh our memory - from the relatively simple ('powers of ten') to the very specialised ('Calabi-Yau manifold' or another 'simply connected space'). And for those particularly interested and familiar with the subject, there is also quite extensive supplementary literature. |

@tipu curate 2

Upvoted 👌 (Mana: 47/67) Liquid rewards.

You did a great work, but please ask boosts for less than 24 hours posts. 🙂